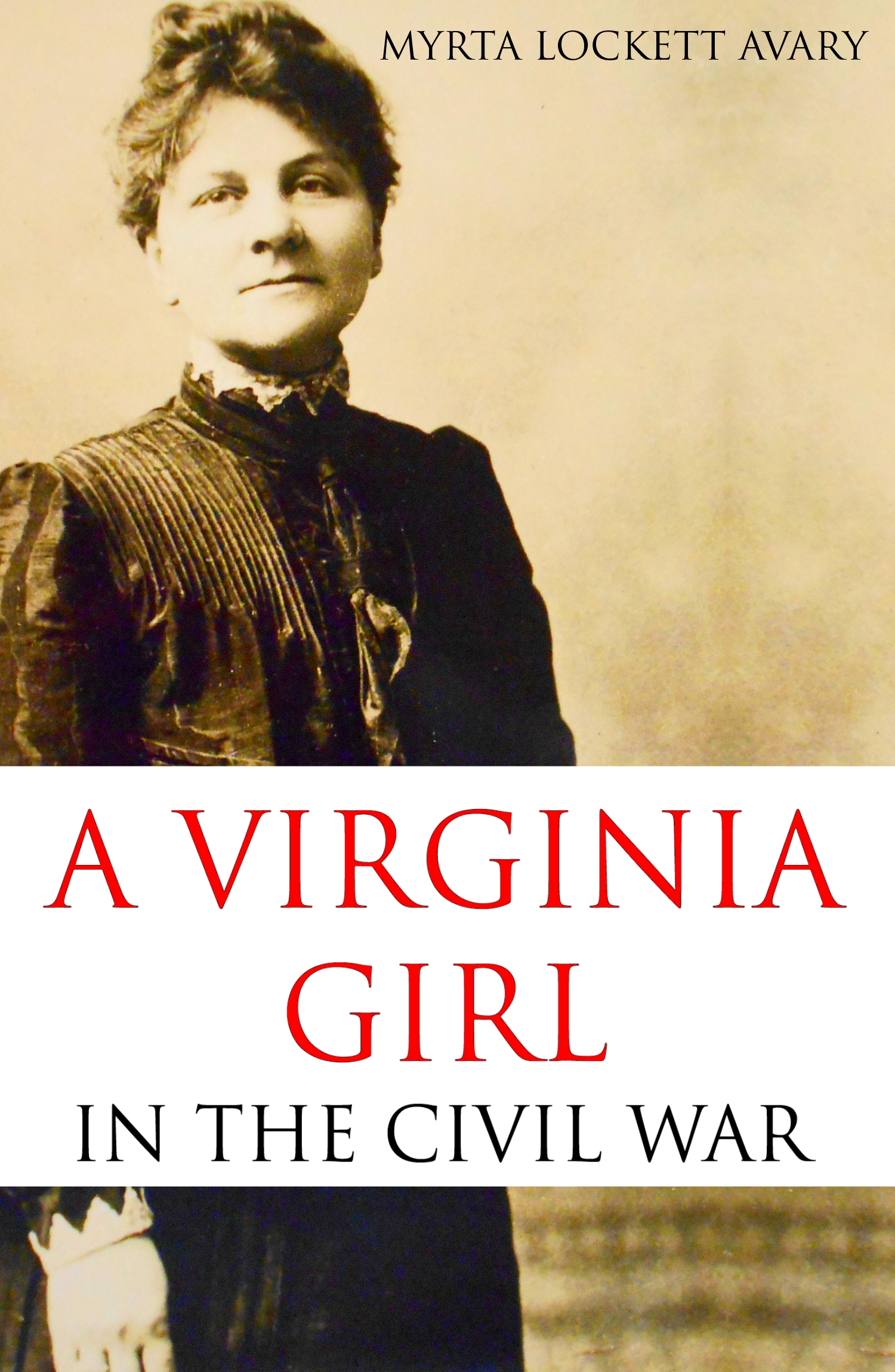

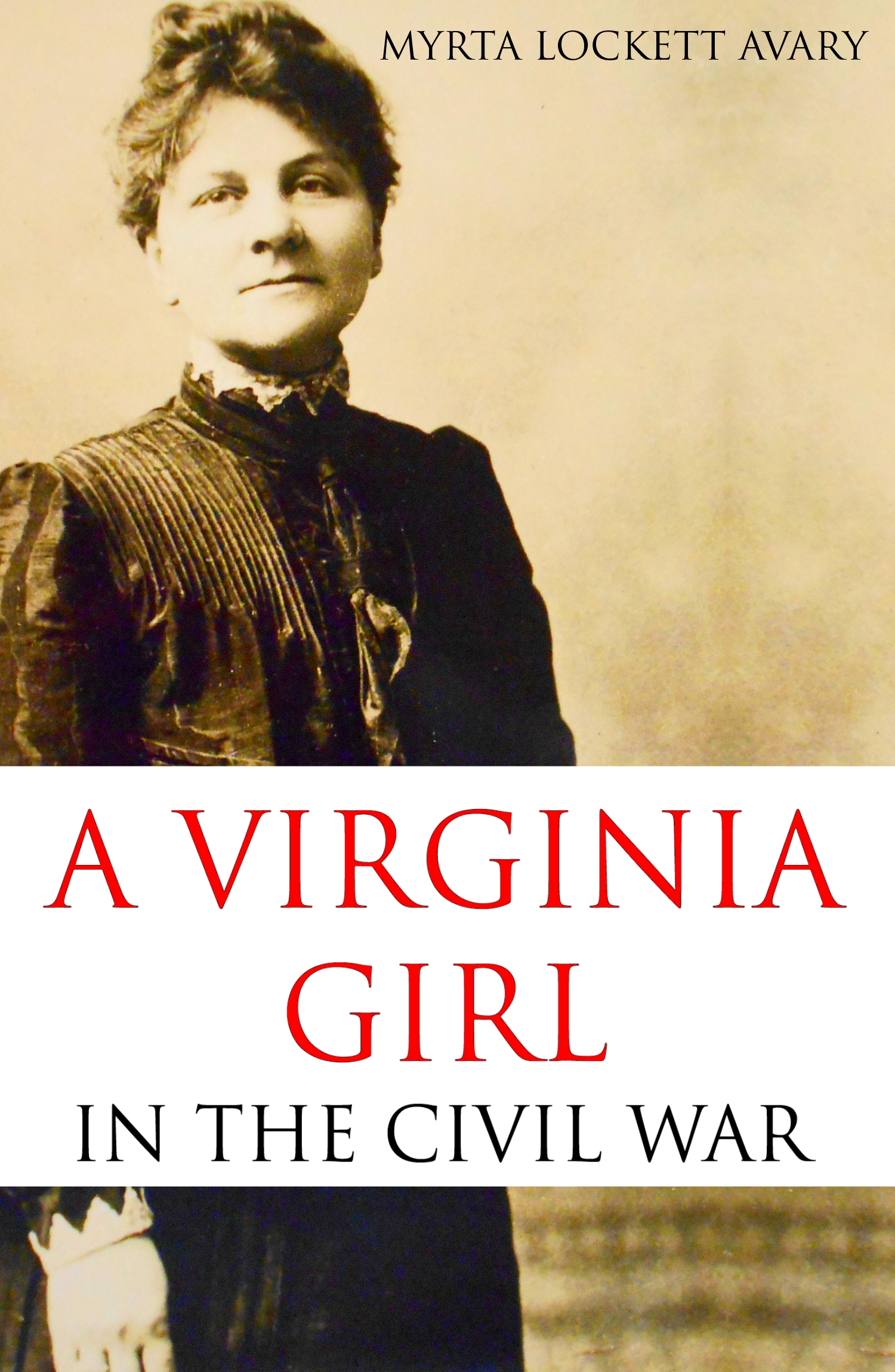

A VIRGINIA GIRL

IN THE CIVIL WAR

1861-1865

BEING A RECORD OF THE ACTUAL EXPERIENCES

OF THE WIFE OF A CONFEDERATE OFFICER

COLLECTED AND EDITED BY

MYRTA LOCKETT AVARY

1903

COPYRIGHT 2015 BIG BYTE BOOKS

Discover more lost history from BIG BYTE BOOKS

PUBLISHERS NOTES

The true tale you are about to read is something of a real-life Gone with the Wind . Though Myrta Avary did not reveal the identity of her heroine, the woman can stand in for a multitude of wives of Confederate officers. What makes her story compelling is the company she kept and the adventures she undertook.

Though only seventeen at the time of her marriage and the outbreak of war, she visited her husband in camp and ventured into Yankee territory in service of the C.S.A. That Myrta Avara was the one to later befriend her and take down her story is fortunate for us. She was the original editor of the famous Mary Chesnut diary, prominently featured in Ken Burns documentary, The Civil War .

Myrta Harper Lockett was born December 7, 1857 to Harwood Alexander Lockett and Augusta Anne Elizabeth Harper in Halifax County, Virginia. The 1860 federal census shows the family estate valued at $12,500 in real estate (nearly $360,000 in 2014 dollars) and $60,500 in personal estate (more than $1.7 million in 2014). The children were home schooled at the family plantation, named Lombardy Grove. Situated at a crossroads, the plantation was a magnet for the high and mighty of the antebellum south. The only formal education Myra had was five months at Miss Betty Carter's School in Boydton, Virginia. They were a slave-owning family whose fortunes would be reduced by the war and emancipation but H.A. Lockett would do well as a merchant after the war. On July 3, 1865, Myrtas father filed for a presidential pardon from his role in the rebellion, granted on that same day.

Myrta clearly wanted to be a writer from a young age. Her first published work was A Night of Terror in Spain published by The Tobacco Plant Newspaper . The story was retracted by the editor and Myrta's parents due to her youth and inexperience. She was only twelve at the time.

By 1880, Myrta was twenty and still living at home on the family farm. She had already begun to publish in newspapers and belonged to a literary society. She married Dr. James Corbin Avary, II in 1884, with whom she had one child who died in infancy.

Myrta wrote for the Atlanta Journal , Atlanta Constitution , and Atlanta Georgian , and later for such publications as The Current Literature , The Illustrated American , The Century , The Outlook , The Christian Herald , and Harper's Bazaar .

The Avarys moved to New York and by 1911 had filed for legal separation. By then she had written and published to successful sales A Virginia Girl in the Civil War (1903), Dixie After the War (1906, a national bestseller and possibly the inspiration for Gone With the Wind ), and she edited A Diary from Dixie as written by Mary Boykin Chestnut (1905). She also published Letters and Recollections of Alexander H. Stephens , the former Confederate Vice-President.

Myrta was active in a very wide community. She worked with a faculty to give poor immigrant children a summer camp at a wealthy land owner's estate Mont Lawn, which is in operation to this day (2015). She also helped establish a convalescent camp for Spanish War veterans in Mont Lawn.

Union General William Tecumseh Sherman famously stated that the southern women were far more bitterly in the fight than the men and would likely carry it on forever if need be. Myrta wrote of her southern sisters, Some are not reconstructed yet. Men can fight back; but women can only sit and endure. This bred an animosity among some rebel women that could be said to exist into the twenty-first century. Family tales of wartime depredations and sacrifice remain.

By the time this book was written, most southerners had reconciled to the outcome of the war and many, including the subject of this work, expressed satisfaction that the flag of a united country once again flew above their buildings. Avarys own mother might have been speaking for the woman in this story when she told her daughter of the burden whites had endured when owning other human beings. She told Avary, I was glad and thankfulon my own accountwhen slavery ended and I ceased to belong body and soul to my negroes.

It was with this background and in this context that Avary wrote her books. They provide a view into a world that Scarlett OHara herself mourned and that Margaret Mitchell wrote about. But Avarys character, unlike Scarlett, was a real person, and her real story is here for you to read.

Myrta Harper Lockett Avary died on February 14, 1946 in Fulton, Georgia. She is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta.

INTRODUCTION

This history was told over the tea-cups. One winter, in the South, I had for my neighbor a gentle, little brown-haired lady, who spent many evenings at my fireside, as I at hers, where with bits of needlework in our hands we gossiped away as women will. I discovered in her an unconscious heroine, and her Civil War experiences made ever an interesting topic. Wishing to share with others the reminiscences she gave me, I seek to present them here in her own words. Just as they stand, they are, I believe, unique, possessing at once the charm of romance and the veracity of history. They supply a graphic, if artless, picture of the social life of one of the most interesting and dramatic periods of our national existence. The stories were not related in strict chronological sequence, but I have endeavored to arrange them in that way. Otherwise, I have made as few changes as possible. Out of deference to the wishes of living persons, her own and her husbands real names have been suppressed and others substituted; in the case of a few of their close personal friends, and of some whose names would not be of special historical value, the same plan has been followed.

Those who read this book are admitted to the sacred councils of close friends, and I am sure they will turn with reverent fingers these pages of a sweet and pure womans lifea life on which, since those fireside talks of ours, the Death-Angel has set his seal.

Memoirs and journals written not because of their historical or political significance, but because they are to the writer the natural expression of what life has meant to him in the moment of living, have a value entirely apart from literary quality. They bring us close to the human soulthe human soul in undress. We find ourselves without preface or apology in personal, intimate relation with whatever makes the yesterday, to-day, to-morrow of the writer. When this current of events and conditions is impelled and directed by a vital and formative period in the history of a nation, we have only to follow its course to see what history can never show us, and what fiction can unfold to us only in parthow the people thought, felt, and lived who were not making history, or did not know that they were.

This is the essential value of A Virginia Girl in the Civil War: it shows us simply, sincerely, and unconsciously what life meant to an American woman during the vital and formative period of American history. That this American woman was also a Virginian with all a Virginians love for Virginia and loyalty to the South, gives to her record of those days that are still the very fiber of us a fidelity rarely found in studies of local color. Meanwhile, her grateful affection for the Union soldiers, officers and men, who served and shielded her, should lift this story to a place beyond the pale of sectional prejudice.

Next page