ALSO BY GLENDA ELIZABETH GILMORE

Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 18961920

Who Were the Progressives? (editor)

Jumpin Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights (coeditor)

Copyright 2008 by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First published as a Norton paperback 2009

Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copright notices, page 621 constitutes an extension of the copyright page.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Manufacturing by RR Donnelley, Bloomsburg

Book design by Dana Sloan

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth.

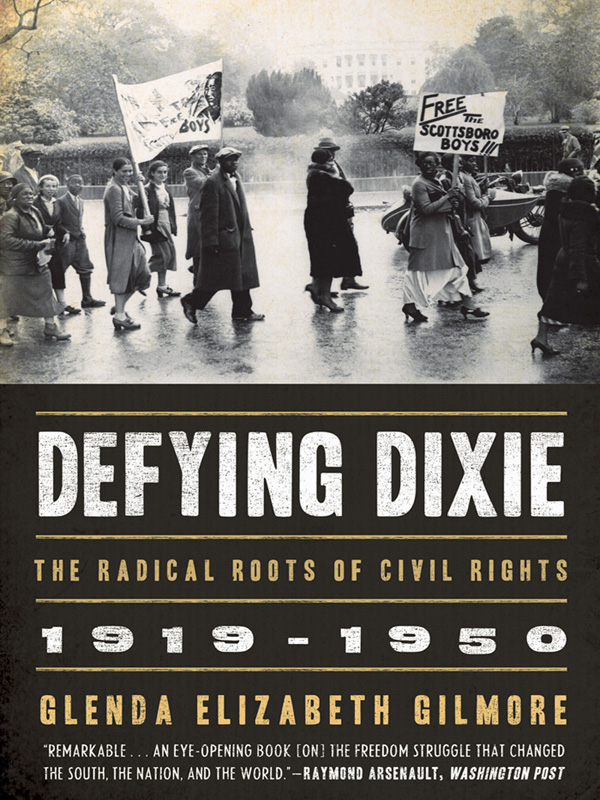

Defying Dixie : the radical roots of civil rights, 19191950 / by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-06244-1 (hardcover)

1. Social justiceSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 2. Social movementsSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 3. RadicalismSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 4. Civil rights movementsSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 5. African AmericansCivil rightsSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 6. Political activistsSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 7. Social reformersSouthern StatesHistory20th century. 8. Southern StatesPolitics and government18651950. 9. Southern StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. 10. Southern StatesSocial conditions20th century. I. Title.

HN79.A13G54 2008

303.48409750904dc22 2007010237

ISBN 978-0-393-33532-3 pbk.

ISBN 978-0-393-34818-7 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To Ben, who hung the moon over Magpieland,

and to Miles, Derry, and Mia-lia,

who dance with us by its light

CONTENTS

The Sun

Is gonna go down

In Dixie

Some of these days

With such a splash

That everybody who ever knew

What yesterday was

Is gonna forget

When that sun goes down in Dixie.

LANGSTON HUGHES, SUNSET IN DIXIE, SEPTEMBER 19411

W hen African Americans used the word Dixie in the first half of the twentieth century, they pronounced the South another country, with its own political and social institutions, upheld by a white supremacist regime. The sun went down in Dixie in the great splash of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and for a while everybody who ever knew/What yesterday was forgot. In the simplified story broadcast across the nation on black-and-white televisions, the heroes of the movement arose directly from the ashes of slavery as the first African Americans ever to challenge the Souths archaic and long-undisturbed system of racial management. With the exception of Rosa Parks, the first woman who ever refused to give up her seat on a bus, the heroes were men, and those men came from black churches, where they had kept the light of freedom burning for a very long time. These nonviolent heroes wanted to vote, send their little children to school, sit down after a weary day, and order a grilled cheese sandwich at Woolworths. According to this view, the civil rights movement started when it burst into white peoples living rooms, brought to them by white media.2

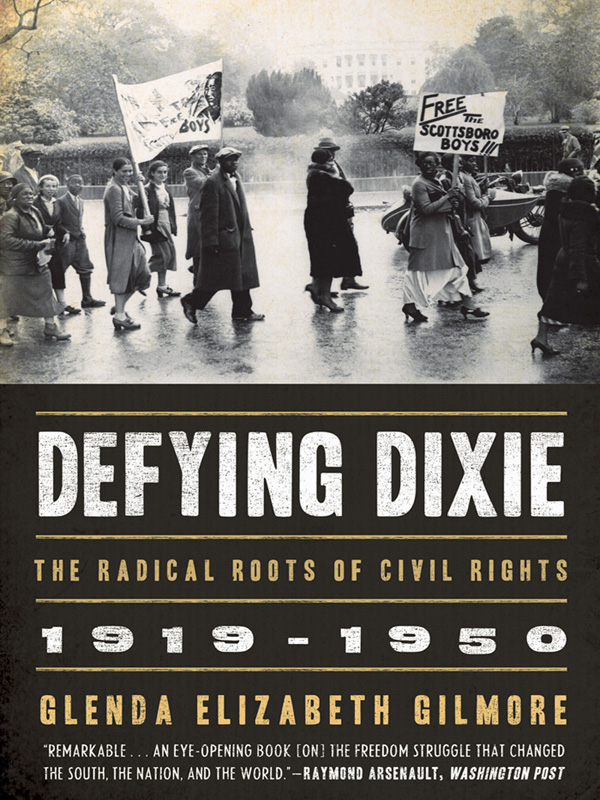

African Americans knew better. Asked by an interviewer in the 1990s when he joined the civil rights movement, an elderly black man in Louisiana responded, Been involved in the movement all my life.3 In the three decades that followed World War I, black Southerners and their allies relentlessly battled Jim Crow, the Souths system of racial hierarchy. Challenges to segregation happened daily on buses across the South, and people went to jail and sometimes died over seating arrangements. There was never a time when black Southerners gave up their political aspirations, and increasing numbers voted in urban areas throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The legal campaign to desegregate education began in 1933.4 These issues, however, never stood as separate goals. They were part of a much larger push for economic justice and a broad vision of human rights that made up what historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall has called the long Civil Rights Movement.5

When I was growing up in the dimming rays of Dixies sunset in the 1950s in Greensboro, North Carolina, I came across clues that a battle had been fought on my home ground. Our long, baking hot drives to Myrtle Beach were punctuated by three strange roadside billboards: THIS IS KLAN KOUNTRY, IMPEACH EARL WARREN, and U.S. OUT OF THE U.N. As a white child I understood the first two as foregone conclusions. THIS IS KLAN KOUNTRY declared the proximate boundaries of southern localism. IMPEACH EARL WARREN warned that the judicial power of the national state stopped here, short of fulfilling its mandate in Brown v. Board of Education. But the thirdU.S. OUT OF THE U.N.gave me pause. I learned all about the United Nations at Sternberger Elementary School, where we made cardboard models of its shiny new headquarters. My teachers told me that it was a beacon beaming U.S. democracy into the dark corners of the world. It might even prevent another war like the one my daddy had fought in. But what did the UN have to do with the South?

Although I could not understand the connections at the time, all three billboards drew the boundaries of the mythical country in which I lived. The nation we knew as Dixie survived into the 1950s because it zealously policed its borders. Within those borders, racial oppression reigned supreme, controlling not only public space but public conversation and private conscience and narrowing the political imagination of even its most defiant subjects. Those who openly protested white domination had to leave, one way or another. Once they left, they could no longer be Southerners. Those who did not grow up within the South would always be outsiders, for they could never be Southerners either. I rose and stood for Dixie until I was twenty years old, when I finally made the connection between my mythical country and racial oppression.

Grown-up white Southerners had always known that Dixie depended on localism, on their right to be left alone to manage their unique Negro Problem. On the eve of the 1950s civil rights movement, the Souths rulers continued successfully to broker deals with both political parties, Congress, and the executive branch to reinforce local power. But for the first time since the Reconstruction amendments the federal judiciary began to recognize black civil rights by extending constitutional guarantees throughout the nation. The remedy? Impeach Earl Warren.

As the third billboard proclaimed, white supremacists took the threat issuing from the court of world opinion just as seriously. After the UN Charter incorporated provisions for human rights, and almost a century after the first secessionist movement, white southern conservatives proposed to secede again: to get the United States out of the United Nations. Since World War I African Americans and their white allies had increasingly brought global politics to bear on domestic racial oppression. In the late 1930s and 1940s a domestic ideal of racial tolerance, necessitated by the demands of fighting Fascism, became the American way, at least rhetorically. If advocating political isolationism in the American century ultimately proved a futile exercise, it was not because southern segregationists did not vigorously pursue it.

Next page