Introduction: On Trembling Earth

The childhood of Southerners, white and colored, Lillian Smith wrote in 1949, has been lived on trembling earth. For one black boy in the small town of Monroe, North Carolina, the first tremor came on a warm September afternoon in 1936.

Emma Williams had sent her eleven-year-old son, Robert, to the post office downtown shortly after one of the regular Friday prayer meetings that met at her home. He was a thick-chested, round-faced, almost cherubic youngster with chestnut-brown skin and a ready smile. What a Friend We Have in Jesus still echoed in his ears as he walked from Boyte Street toward the railroad. As Robert crossed the gravel railroad bed, he met a black man walking the tracks, clutching a pint of whiskey and singing, Trouble in mind, I'm blue / But I won't be blue always / Because the sun is gonna shine in my back door someday. The boy smiled to himself and headed on toward the courthouse square in the middle of Monroe, not suspecting that what he would witness there would shake his whole world.

Walking down Main Street, Williams watched a white police officer accost an African American woman. The policeman, Jesse Alexander Helms Sr., an admirer once recalled, had the sharpest shoe in town and he didn't mind using it. His son, U.S. Senator Jesse Helms, remembered Big Jesse as a six-foot, two hundred pound gorillawhen he said smile, I smiled.

Knowledge of such scenes was as commonplace as coffee cups in the American South that had recently helped to elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt. For the rest of his life, Robert Williams repeated this searing story to friends, readers, listeners, reporters, and historians. In the late 1950s, Williams used the story to help inspire African American domestic workers and military veterans of Monroe to build the most militant chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the United States. He preached it from street corner stepladders to eager crowds on 7th Avenue and 125th Street in Harlem and to Muslim congregants in Malcolm X's Temple Number 7. He bore witness to its brutality in labor halls and college auditoriums across the United States. It contributed to the fervor of his widely published debate with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1960 and fueled his hesitant bids for leadership in the black freedom struggle. Its merciless truths must have tightened in his fingers on the night in 1961 when he fled Ku Klux Klan terrorists and a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) dragnet with his wife and two small children, a machine gun slung over one shoulder. Williams revisited the bitter memory on platforms that he shared with Fidel Castro, Ho Chi Minh, and Mao Zedong. He told it over Radio Free Dixie, his regular program on Radio Havana from 1962 to 1965, and retold it from Hanoi in broadcasts directed to African American soldiers in Vietnam. It echoed from transistor radios in Watts and from gigantic speakers in Tiananmen Square. The childhood story opens the pages of his autobiography, While God Lay Sleeping, which Williams completed just before his death on October 15, 1996.

To be sure, one moment in one life rarely changes history. But we can find distilled in the anguish of that eleven year old historical realities that shaped one of the South's most dynamic race rebels and thousands of other black insurgents: African American cultural resilience; white racial violence; the perilous intersection of race, gender, and sexualized brutality; the persistent national failure, a century after the fall of slavery, to enforce equal protection of the laws; and the physical and psychological necessity for African American self-defense. That moment marked Robert Williams's life, and his life marked the African American freedom movement in the United States.

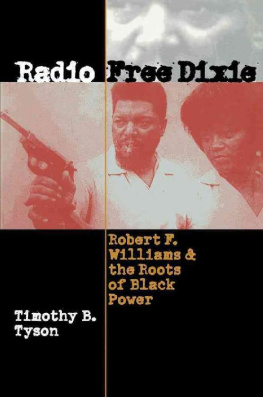

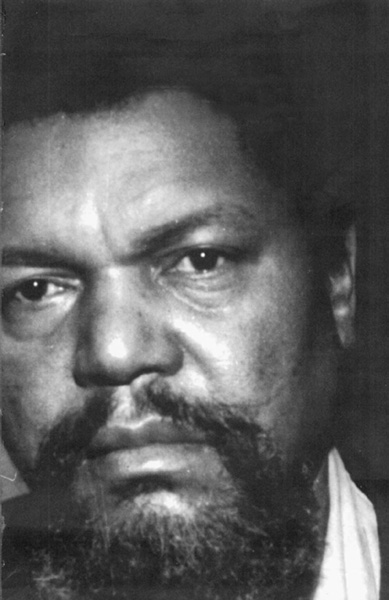

This is the story of one of the most influential African American radicals of a generation that toppled Jim Crow, created a new black sense of self, and forever altered the arc of American history. Robert F. Williams shadows these pages, a troubled intellectual, a fiery prophet, a courageous grassroots leader whose outbursts sometimes came back to haunt him, but the inner wellsprings of his mind and spirit are probably not to be found here. Though this is a biography, it is as much the story of a political movementand a political momentas it is the portrait of a political man. The life at its center is as important for the truths it reveals as for the things it accomplished.

The life of Robert Williams teaches us that the African American freedom movement had its origins in long-standing traditions of resistance to white supremacy. His story underlines the decisive racial significance of World War II. Both his victories and his defeats reveal the central importance of the Cold War to the African American freedom movement, giving black Southerners leverage to redeem or repudiate American democracy in the eyes of the world. Likewise, these struggles reveal the crucial impact of sexuality and gender in racial politics. His defianceand that of thousands of other black activiststestifies to the fact that, throughout the civil rights era, black Southerners stood prepared to defend home and family by force. The life of Robert F. Williams illustrates that the civil rights movement and the Black Power movement emerged from the same soil, confronted the same predicaments, and reflected the same quest for African American freedom.

As if to dramatize the point, Rosa Parks, whose refusal to surrender a bus seat in Montgomery in 1955 had come to symbolize the nonviolent civil rights movement, mounted the pulpit of a church in Monroe, North Carolina, on October 22, 1996. The body of Robert F. Williams lay before her, dressed in a gray suit given to him by Mao Zedong, his casket draped in the red, black, and green Pan-African flag favored by the followers of Marcus Garvey. She was delighted, Rosa Parks told the hundreds of mourners, to find herself at the funeral of a black leader who had died peacefully in his bed. She told the congregation that she and those who walked alongside Martin Luther King Jr. in Alabama had always admired Robert Williams for his courage and his commitment to freedom. The work that he did should go down in history and never be forgotten.