For my wife and daughters, who indulge and support my writing.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

P.O. Box 667

Names: Motavalli, Jim, author.

Title: The real dirt on Americas frontier legends / Jim Motavalli.

Description: First edition. | Layton, Utah : Gibbs Smith, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: LCSH: West (U.S.)Biography. | ExplorersWest (U.SBiography. | Frontier and pioneer lifeWest (U.S.) | LCGFT: Biographies. | Legends.

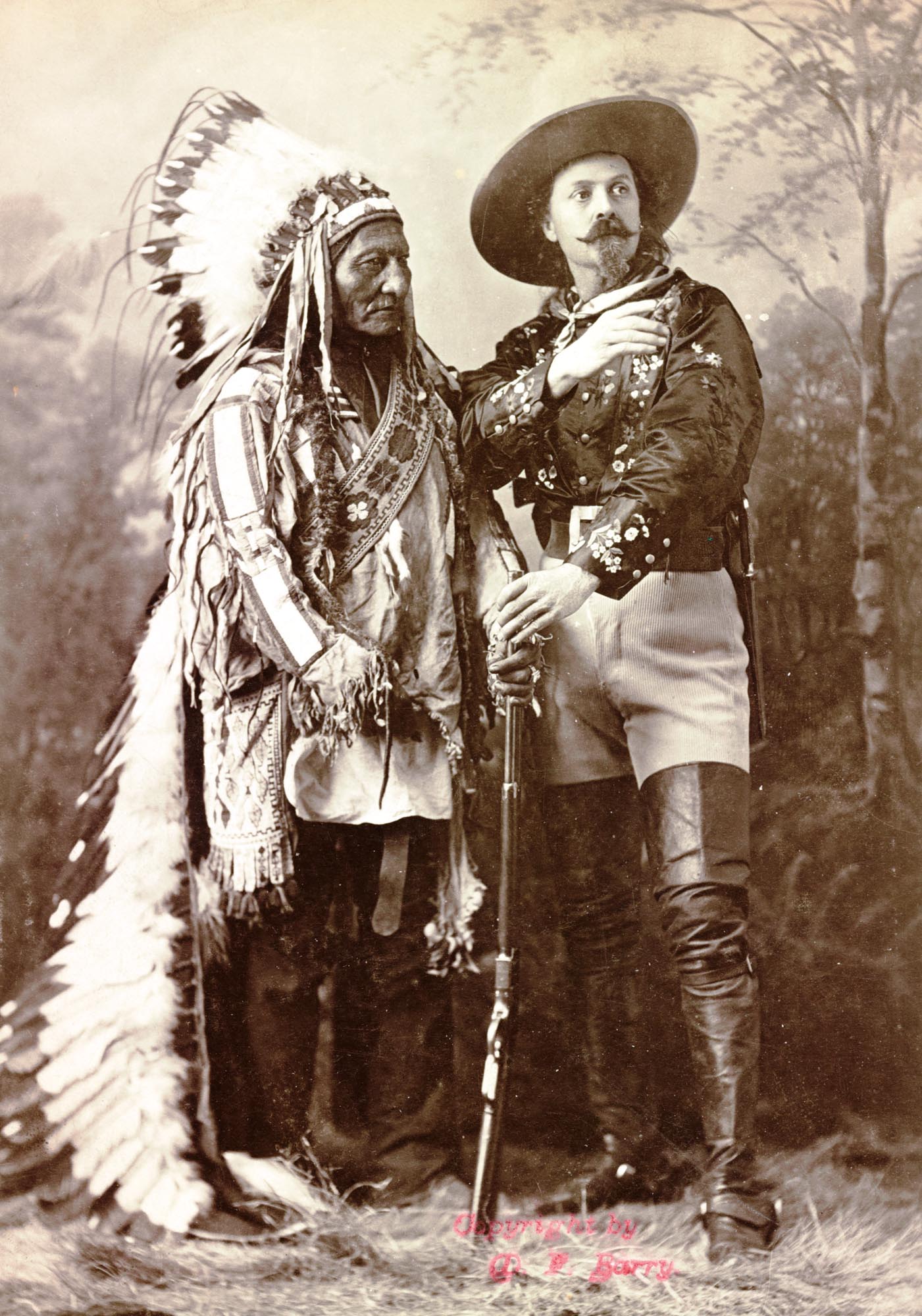

Title page photo: Buffalo Bill with Sitting Bull, who appeared regularly in his Wild West shows. (Library of Congress)

Preface

We Were Misinformed:

Myths in America's Frontier Lore

The American frontier pushed continuously west from the 1630s to the 1880s, at the same time it was also moving both north (into Maine) and south (all the way to Florida). But it was the westward imperative that caught the publics imagination. In his historic speech at the 1893 Worlds Columbian Exposition in Chicago, historian Frederick Jackson Turner expounded his frontier thesis, which held that the existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.

But for the western frontier to get settled, there had to be advance scouts, explorers whosometimes inadvertentlymade the wilderness safe for civilization. These mountain pioneers, trappers, and tradersextant after 1810were a motley crew indeed, and often far from heroic.

True mountain men were never numerousmaybe there were three thousand of them, according to the 1980 Marriage and Settlement Patterns of Rocky Mountain Trappers and Traders. Only half were Anglo-Americans, from such places as Kentucky, Virginia, the Louisiana Territory, and points east. A quarter were either French-Canadian or French-American. The rest were African-American, Spanish-American, Native Americans, or Mtis (mixed ancestry, Native American and European-American).

Their era didnt last longthe insatiable lust for furs, unmediated by anything resembling a conservation plan, meant that the great natural resources (and beavers in particular) were largely played out by the 1840s. But because the public couldnt get enough frontier tales, no matter how tall, many of these colorful figures were enshrined in legend as true American pioneers.

If trapping wasnt as lucrative as before, the mountain men found they could get work as guides, scouts, and Indian fighters. And then there were new opportunitieson stage.

No less a figure than legendary P. T. Barnum had an early hand in creating the legend of the American West. According to Michael Walliss The Real Wild West, it was in 1843 that Barnum encountered a herd of fifteen buffalo near Boston and promptly bought them for seven hundred dollars, later staging The Great Buffalo Hunt, complete with lariats wielded by pretend Indians.

Some twenty-four thousand people went to see the animals in Hoboken, New Jersey (admission was free, but Barnum had chartered the ferries from New York and pocketed the thirteen-cent roundtrip fee), and many fled in terror when the herd of buffalo broke through a fence and then took shelter in a nearby swamp. Plenty of other people came to a later Wild West show that Barnum staged. When a party of Indians visited President Abraham Lincoln in 1864, Barnum waylaid them to attract paying customers to his New York museum. Introducing an unsuspecting Yellow Bear, the chief of the Kiowas, Barnum described him as probably the meanest, black-hearted rascal that lives in the Far West.

P.T. Barnum somewhere between 1860 and 1864. He got in early on the Wild West flim-flam. (Charles D. Fredricks & Co./Library of Congress photo)

We think we know a lot about Lewis and Clark, Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass, Jeremiah Johnson (whose actual name was John Liver-Eating Johnston), Nature Man Joe Knowles, William Buffalo Bill Cody, and their like, but in fact much of what we think we know is a mishmash from sensationalized newspapers, dime novels and old penny dreadfuls (usually written by ghostwriters who never left their city offices), Wild West shows, highly speculative third-hand accounts, and Disney movies from the coonskin cap days. Fact and fiction have intermingled in a fairly alarming way.

How popular were dime novels in their day (1860 to about 1900)? Very. New Yorkbased Beadle & Company published its first short book, Malaeska: The Indian Wife of the White Hunter, in 1860, and its Seth Jones; or, The Captives of the Frontier (written by a twenty-year-old schoolteacher who lived most of his life in New Jersey) sold five hundred thousand copies.

By 1864, according to the North American Review, Beadle had more than five million novels in circulationincredible in those days of a less-literate, less-populous America. But the company was dead by 1896.

Dime novels made a star out of Edward Z. C. Judson, who wrote under the pen name Ned Buntline, and the real people he wrote about became famous. He met William Frederick Cody out west, and made him a household name with his much-reprinted 1869 Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men.

Edward Z. C. Judson, who wrote under the pen name Ned Buntline, churned out dime novels by the dozens. (Sarony photo/Wikipedia)

Exaggeration was part of the natural idiom of the West, reports American Heritage. No boast was too big, no tall tale too outrageous. Men declaimed ridiculous brags that ran on to considerable length: they were ring-tailed roarers, half-horse, half-alligator; they were sired by a hurricane and rode the lightning, and on and on.

Further, the frontiersmen were products of their times, which generally saw nature as a cornucopian bounty without cease. The Pilgrims landed in a pristine wilderness but (after deforested England) found it dark and forbidding. The concept of stewardship or living in harmony with nature is mostly applied to these people in an act of revisionist wish fulfillment.