Annabel Simms

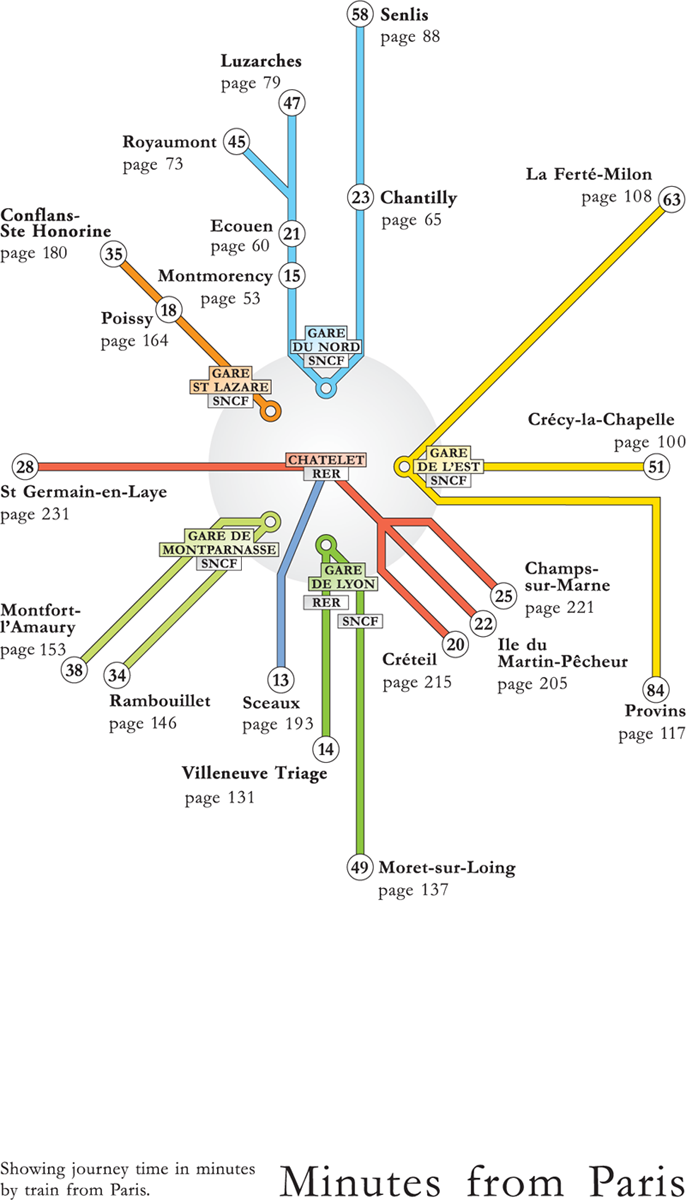

An Hour from

Paris

Contents

Preface

Several years ago I found myself in the middle of a wood, as completely lost as if I were in Africa, rather than 19 kilometres from Paris. Three paths lay in front of me with no indication of where they might lead and there was not a soul in sight. It suddenly occurred to me that no one knew where I was and that I would never dream of venturing out alone like this near London.

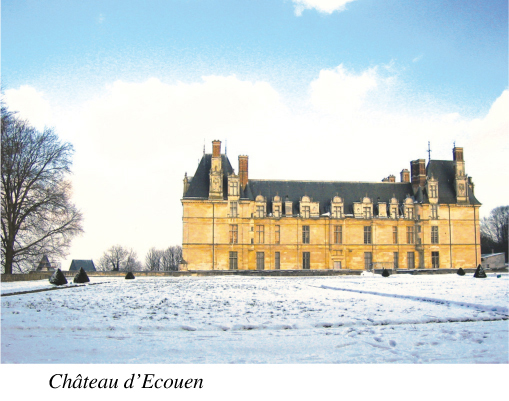

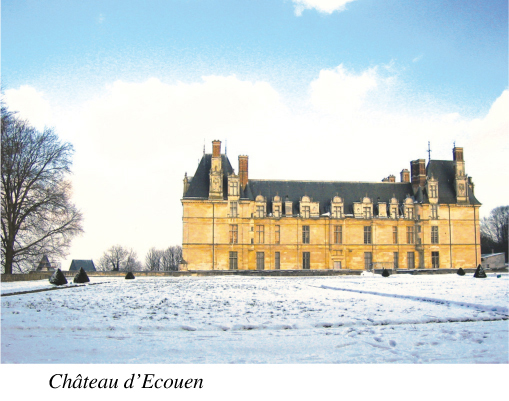

On impulse I took the left path, which soon brought me to houses at the edge of the wood and knocked on the door of the nearest one. Five minutes later, following the owners directions through the same wood, I saw the rooftops of an elegant chteau emerging through the trees and came out onto a sweeping lawn leading straight up to it. Feeling as if I had stepped into a fairytale, I skirted the chteau, which looked as if it might vanish as unexpectedly as it had appeared, and peeked over a stone balustrade to the left.

Sunny rolling countryside lay below me, stretching into the distance as far as I could see, crossed by the moving shadows of the clouds overhead. A few planes purred in the distance and I realised I was under the flight path to Charles de Gaulle airport. Otherwise, I could have believed myself back in the 16th century, when the chteau behind me had been built.

This particular chteau houses the Museum of the Renaissance at Ecouen, 21 minutes from Paris by train. I had rung the Museum and been told that it was about five kilometres on foot from the station. In fact it is just over one kilometre and the woodland paths are now signposted. But it was this early experience that first made me aware of just how interesting and accessible the countryside around Paris is, and how little-known to the French themselves, as well as to foreigners.

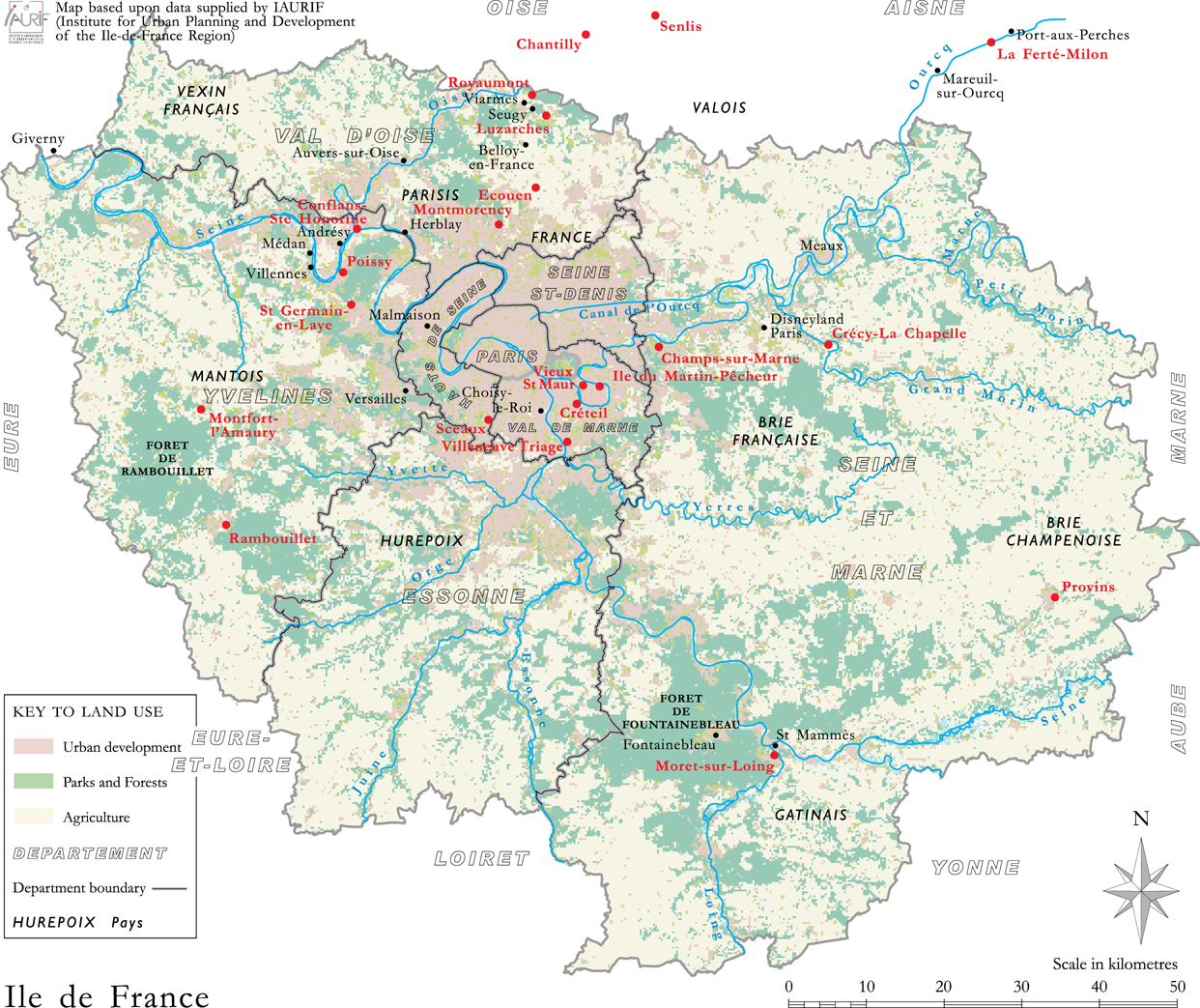

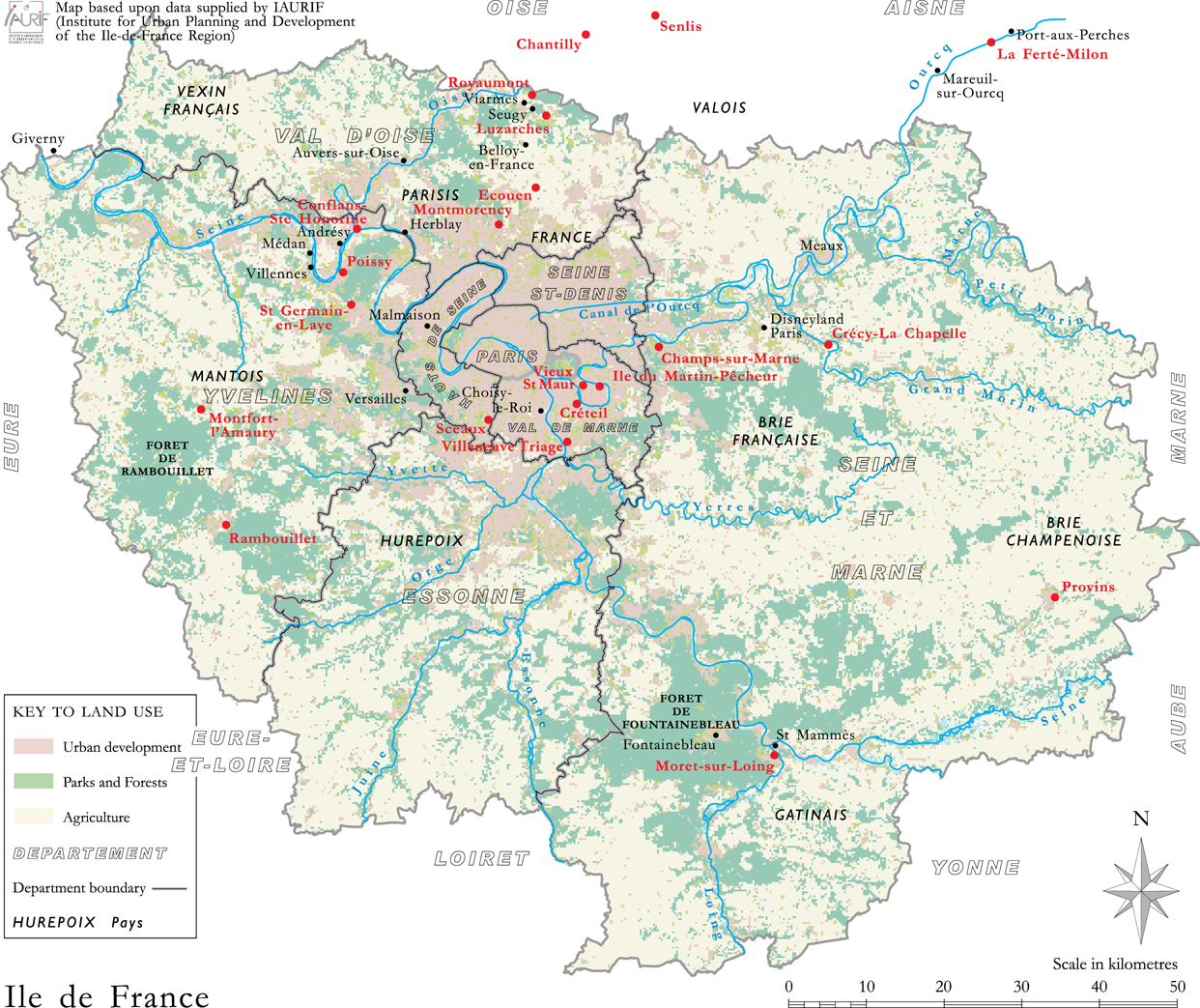

As I began to explore further afield the phrase Ile de France gradually began to take on colour and meaning. The rolling countryside I had seen from the chteau at Ecouen is part of the old Pays de France, the fertile plain surrounded by rivers to the north of Paris that first made the city prosperous. Its rulers slowly extended their dominion over the rest of the country, which became known simply as France. The Ile de France contains the key to the history of the whole country. Paradoxically, it is also one of the least-visited parts of France, overlooked by foreign visitors with their sights set on Paris, while modern transport now whisks Parisians themselves off to ever more remote and exotic destinations.

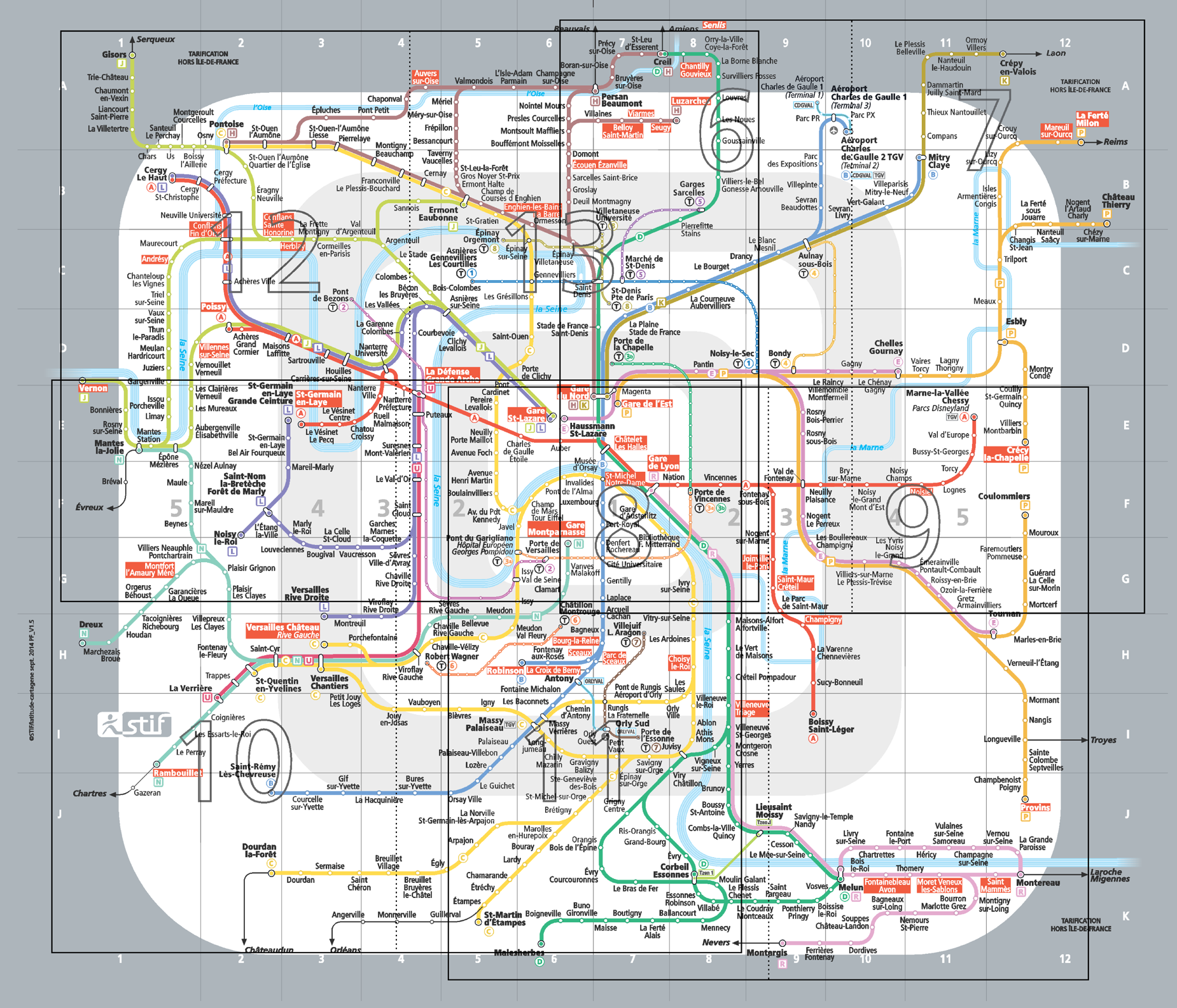

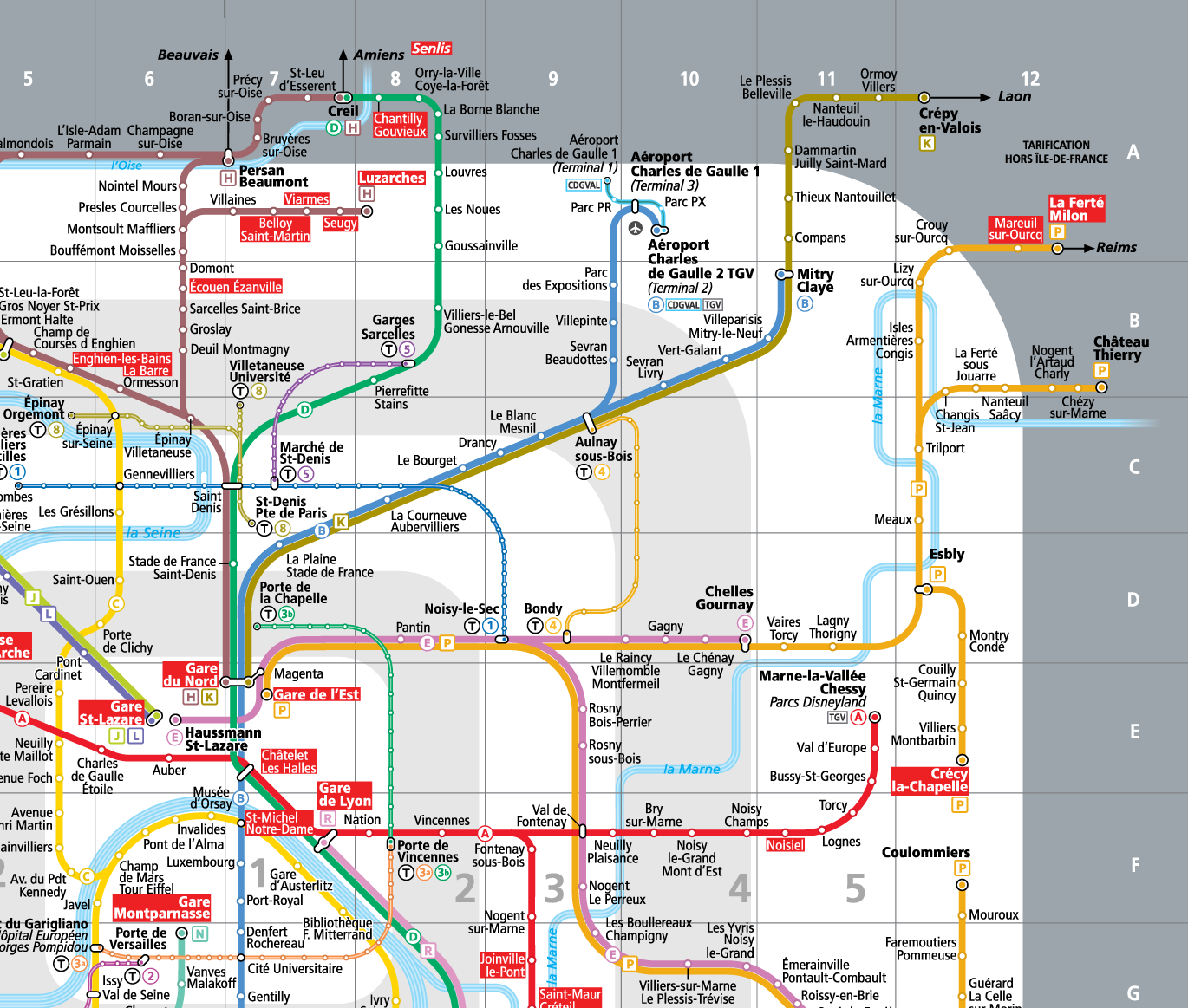

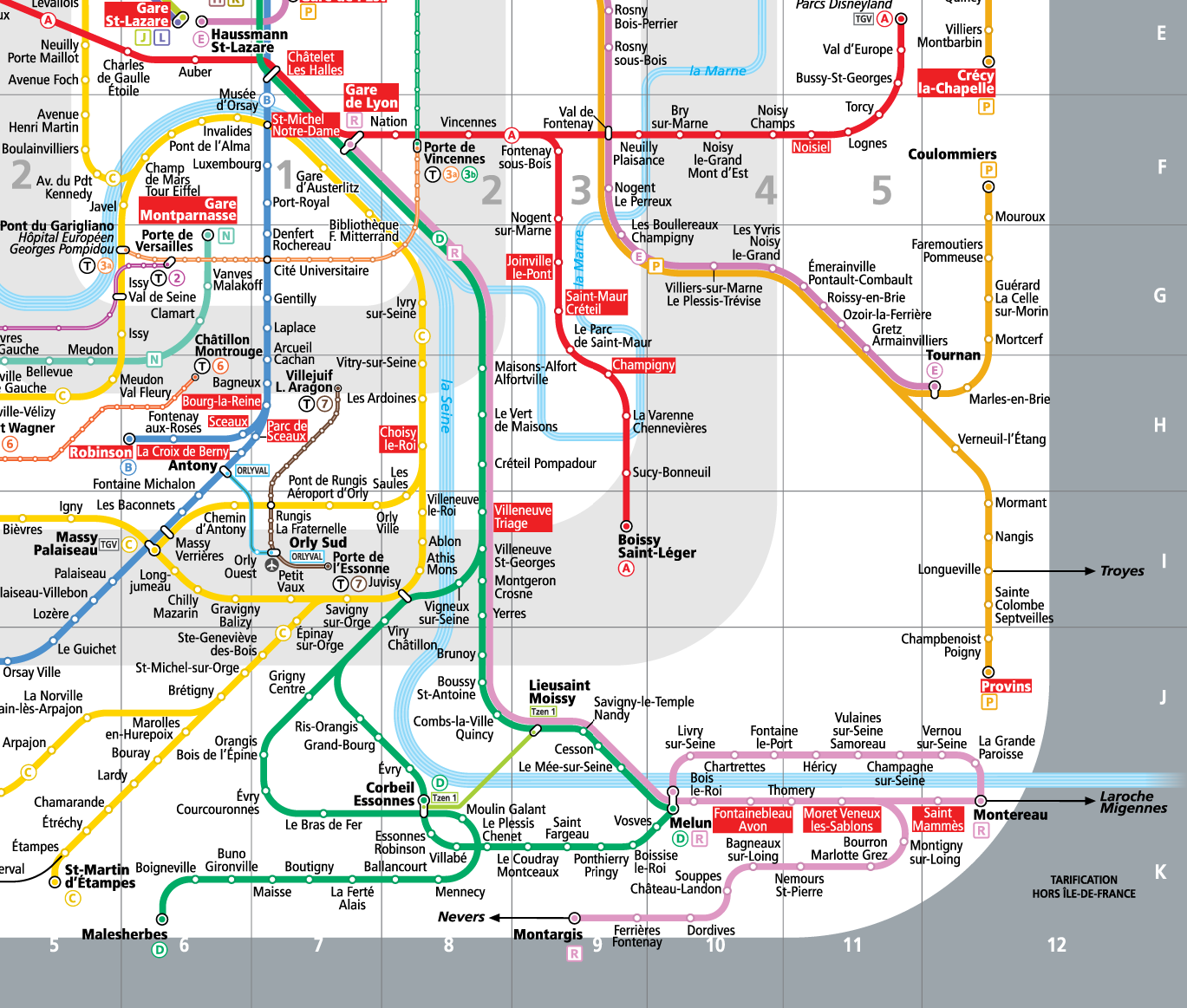

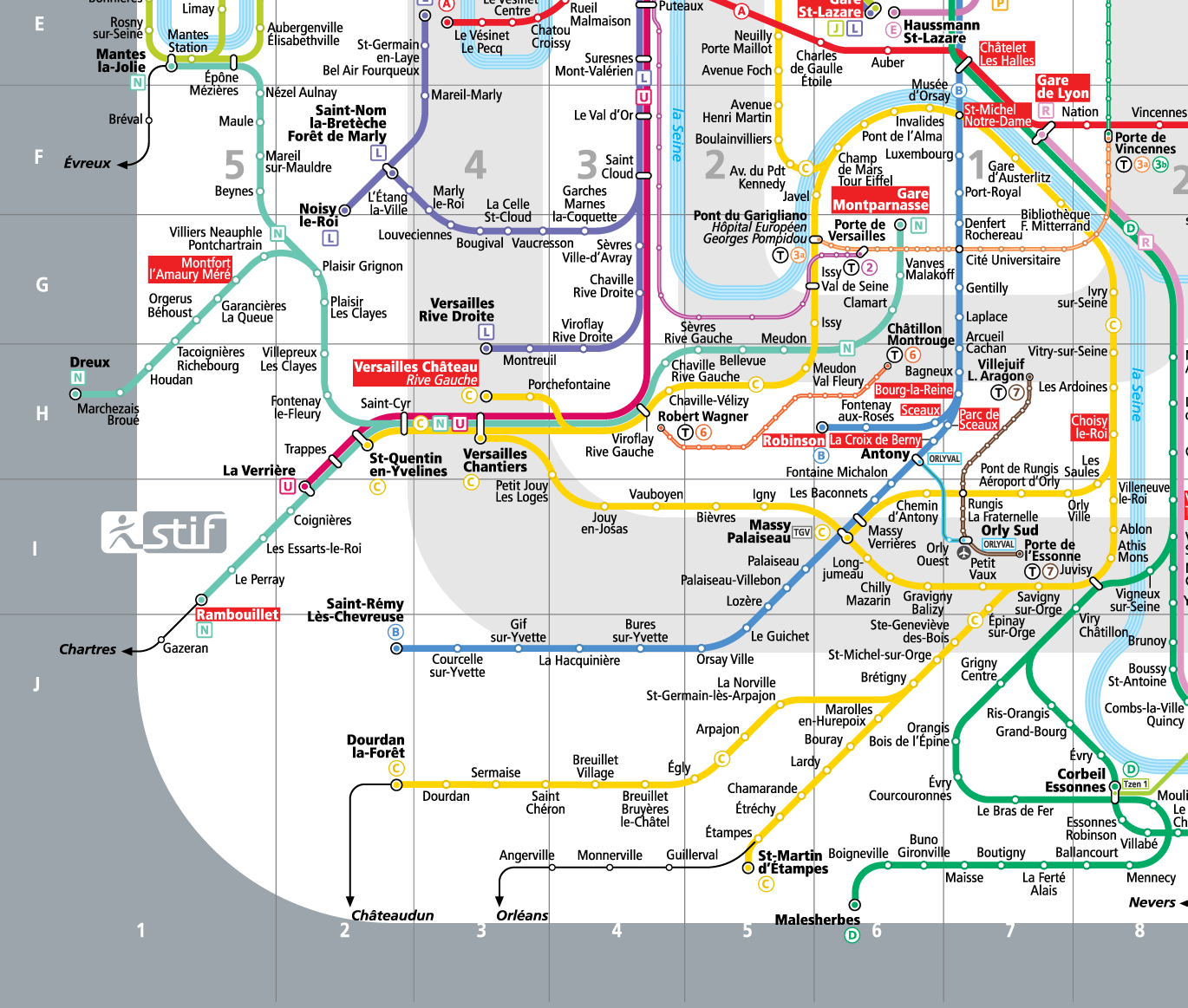

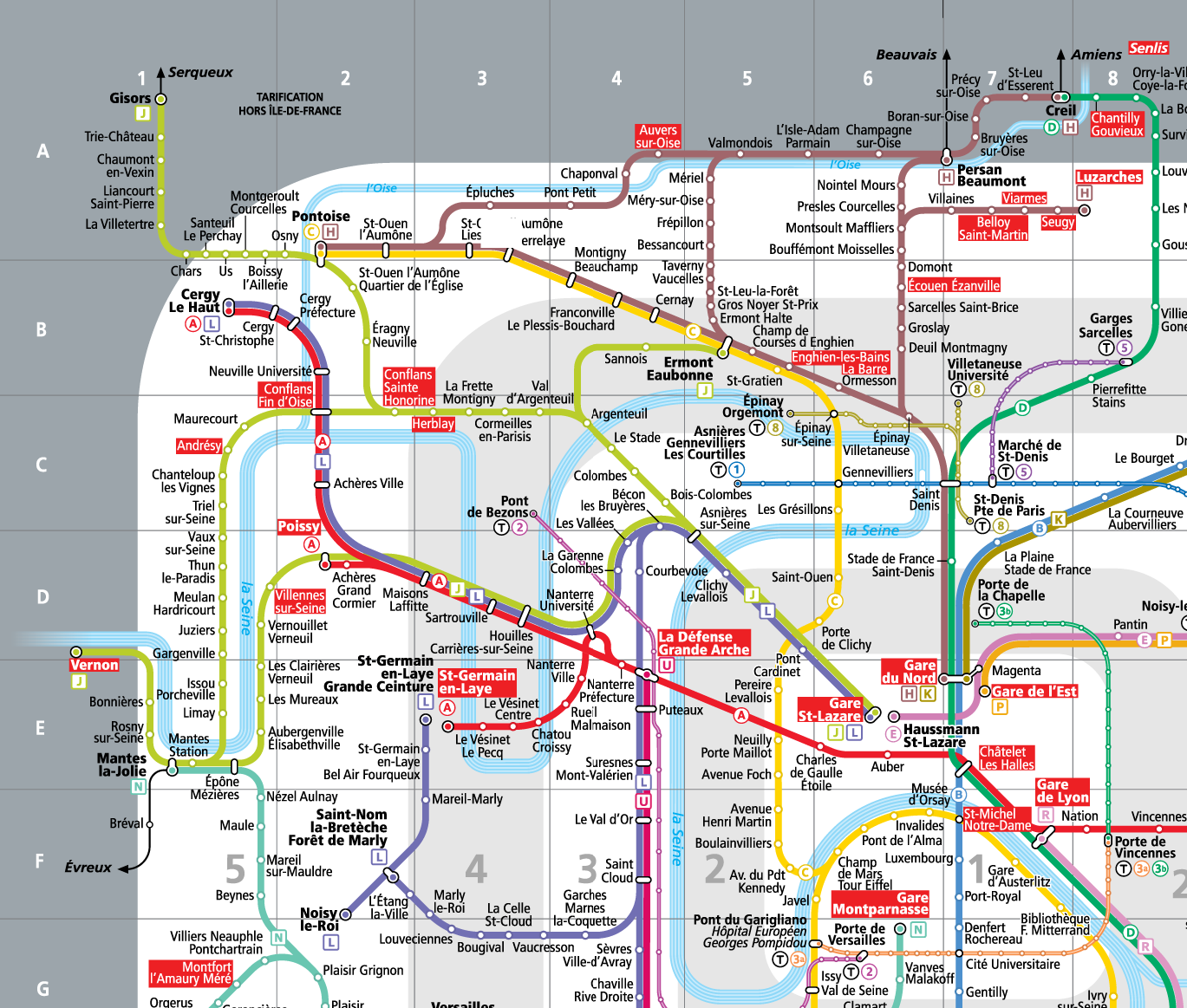

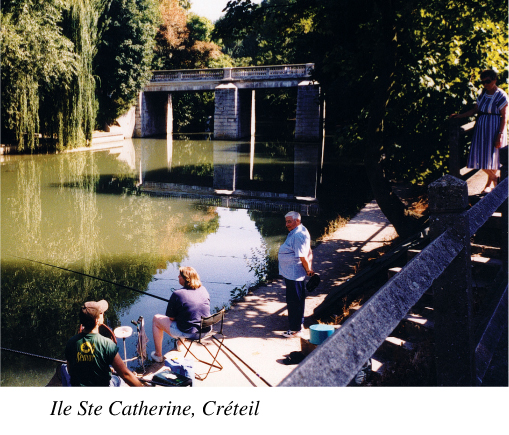

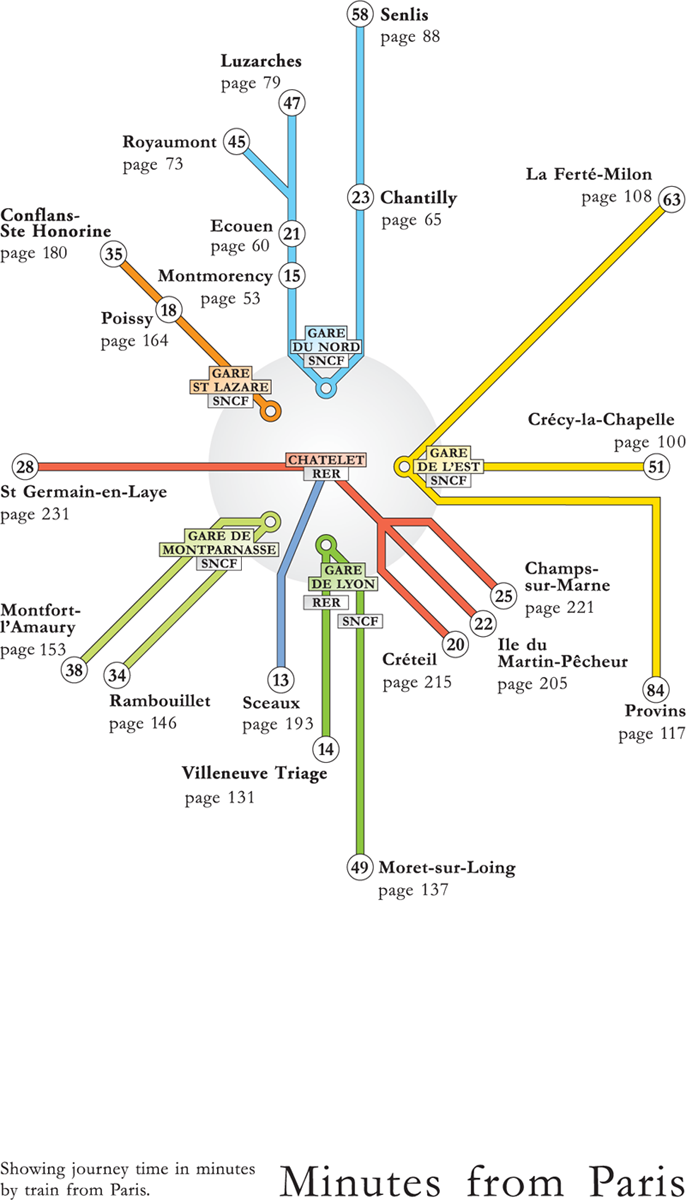

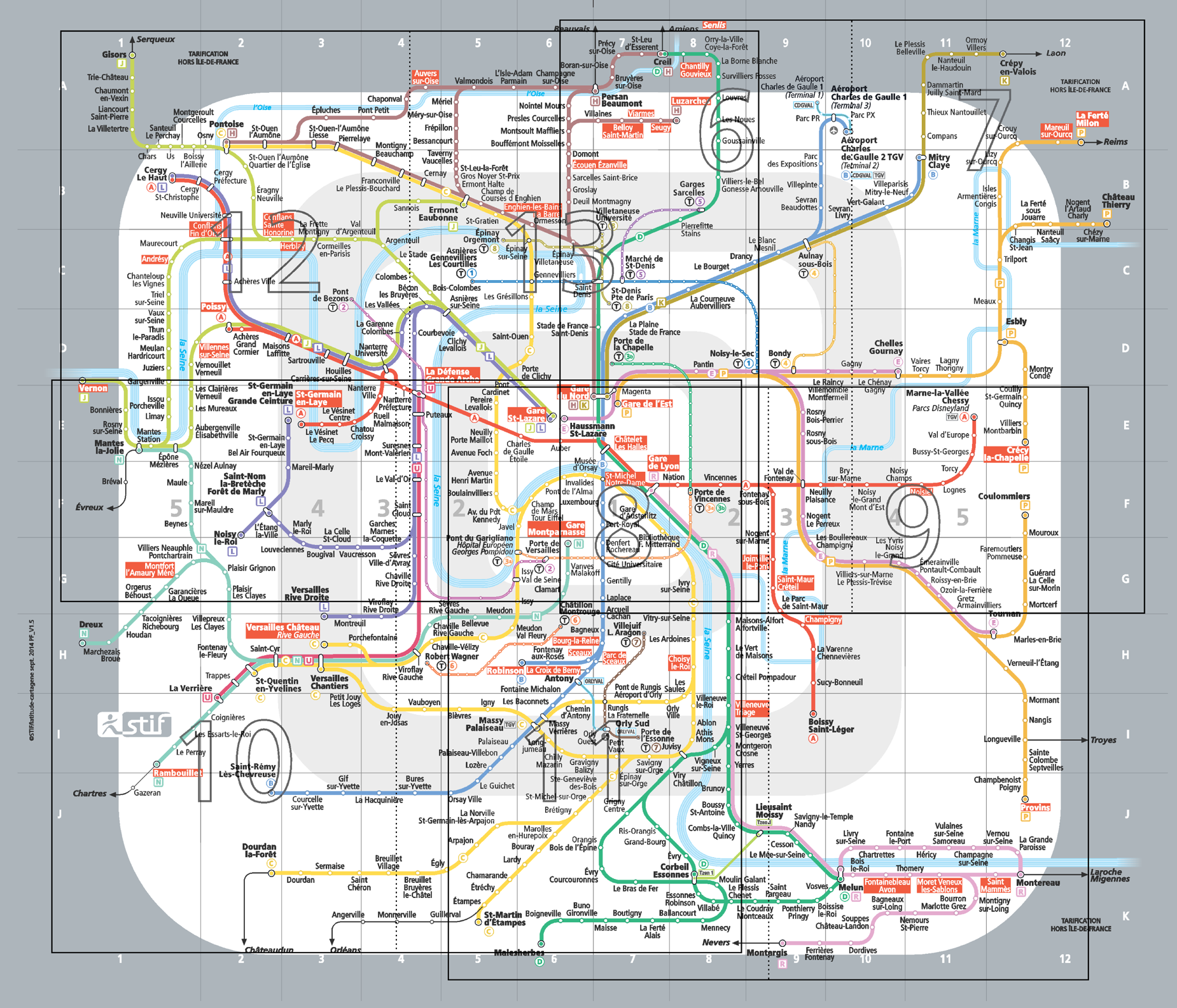

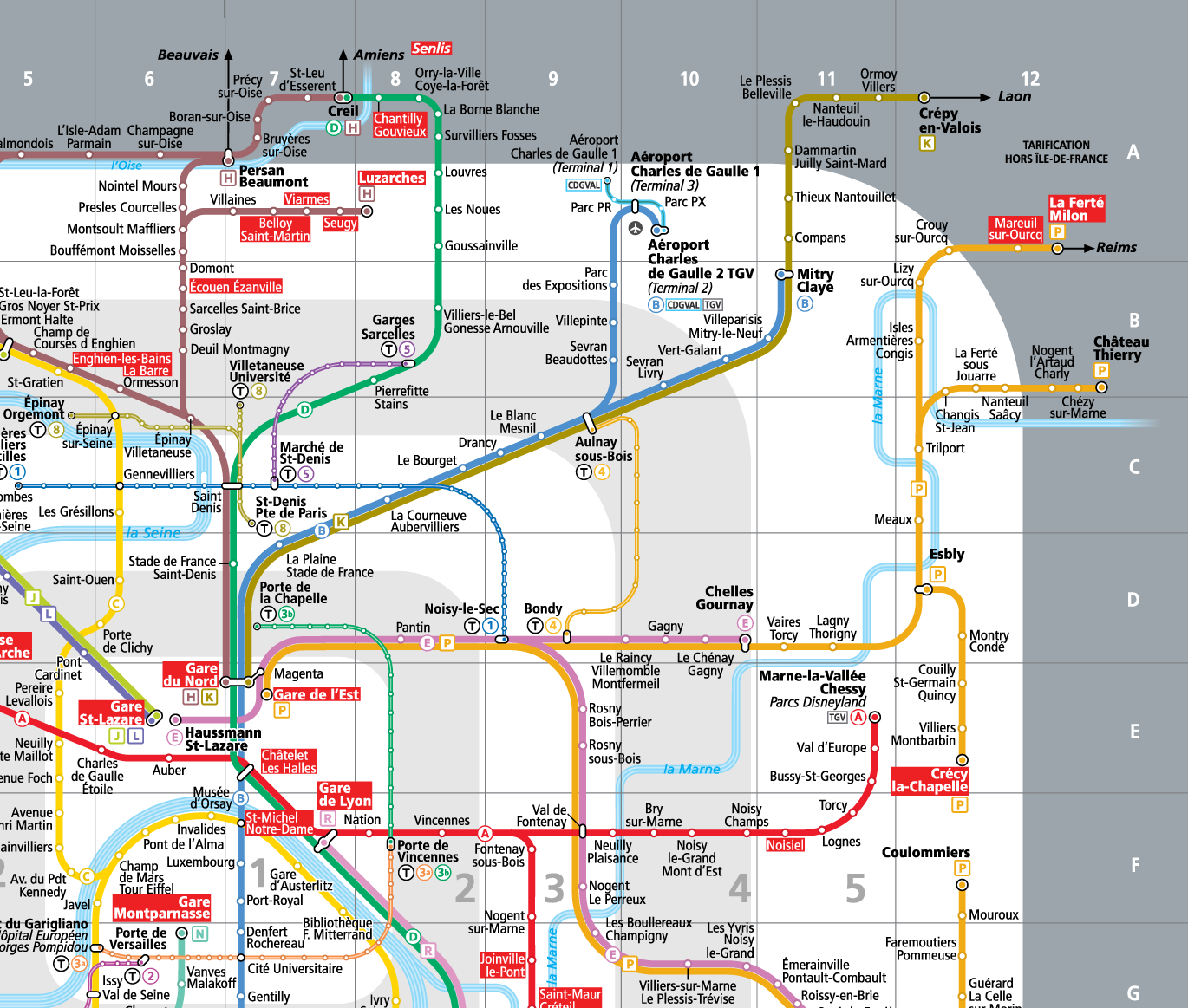

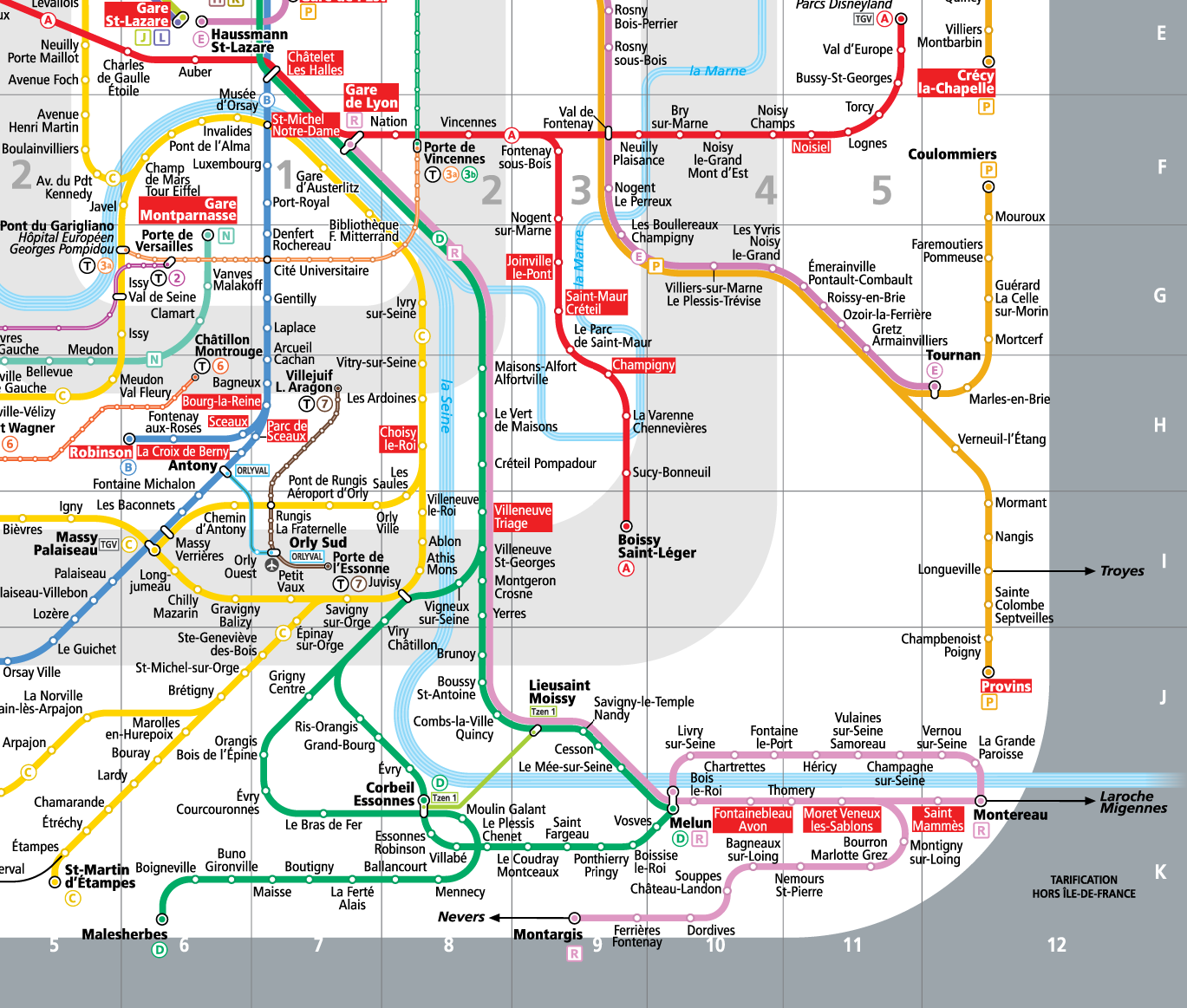

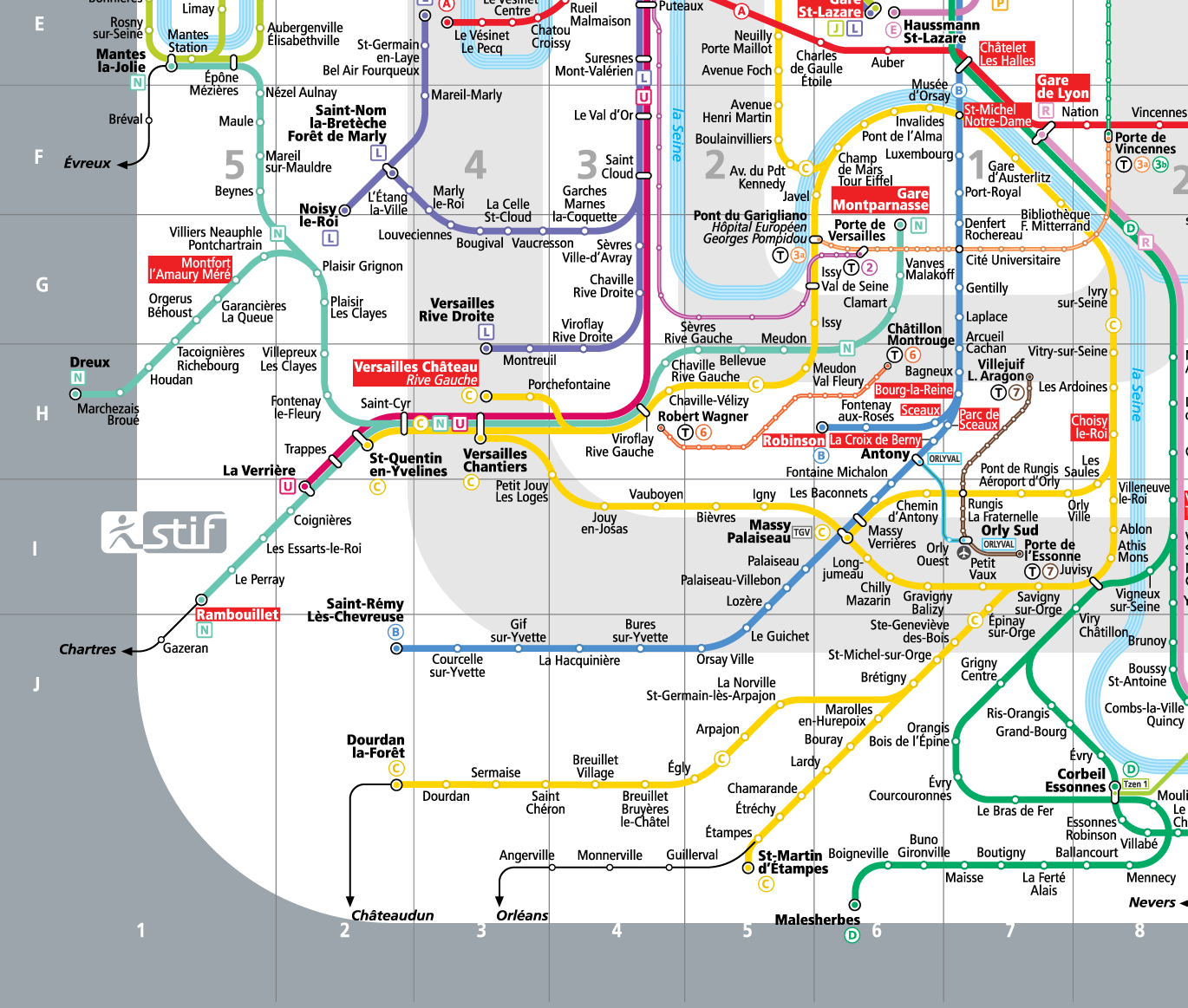

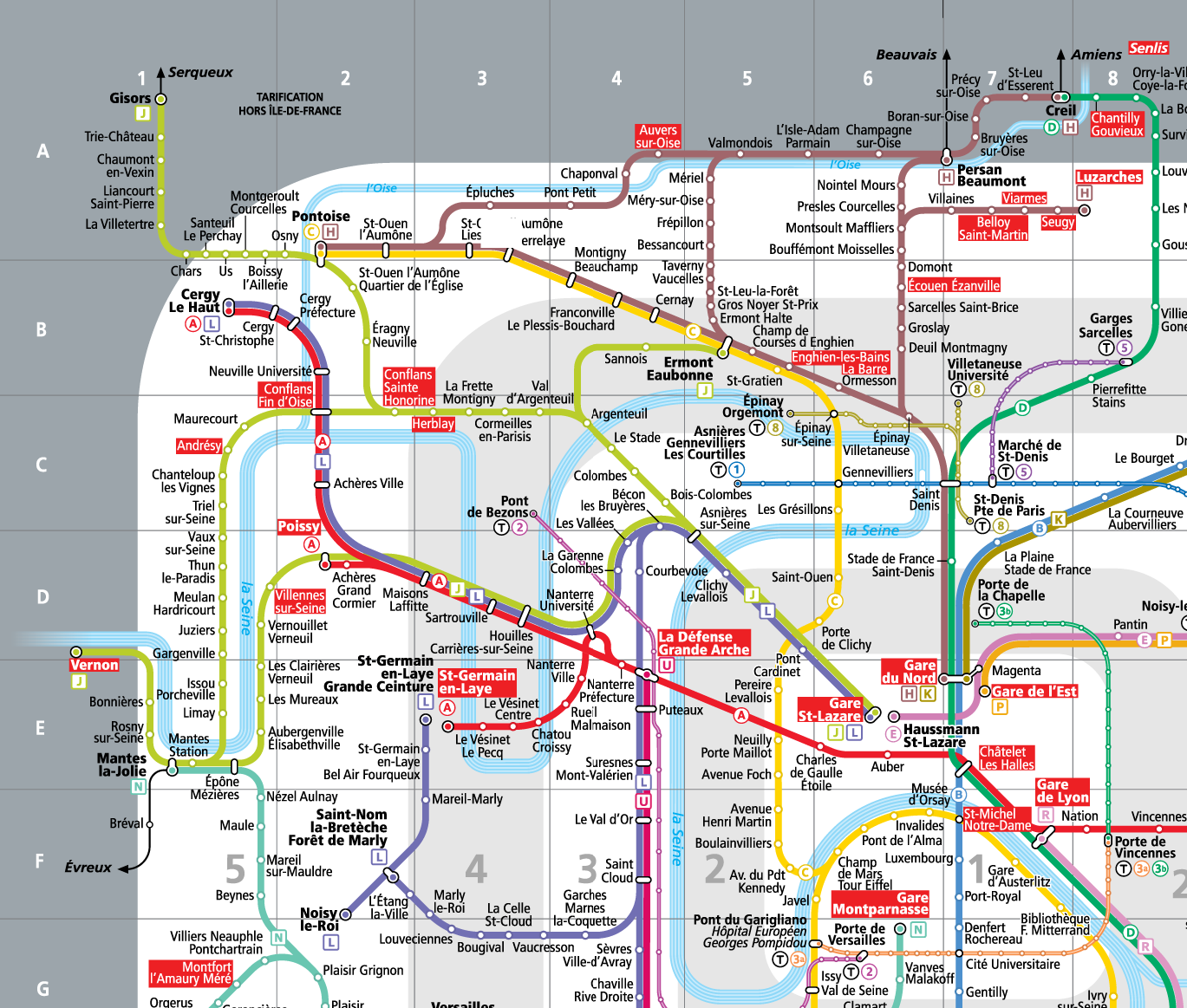

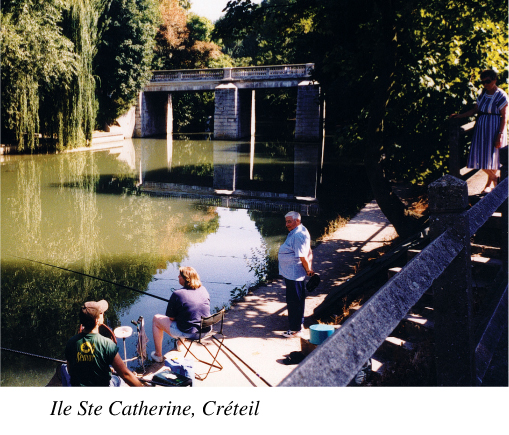

As a result, large parts of the Ile de France, although easily accessible from Paris, have escaped the effects of mass tourism. I began to appreciate the incongruity of using efficient commuter trains, uncrowded at weekends, to arrive less than an hour later at some quiet, unassuming place so remote from Paris as to feel like another world. I would be charmed by the back streets of a tiny medieval town, by the French families spending hours over Sunday lunch in a country restaurant or by the discovery of a riverside footpath leading to another village and railway station. Arriving by train makes a difference. Where there are cars, there will be people, so you are actually more likely to have the countryside to yourself, especially on a Sunday, if you arrive by train. I have found that apparently remote parts of the forests in the Ile de France, easily accessible only from a car-park, are far more crowded than the parts of the same forest which are close to a station. And if you are in a car, your perception of a place is unconsciously coloured by where you have come from and where you can get to next. Your time-scale is the one you carry with you, not the one imposed by the place itself, and you are less likely to notice the fascinating details that would strike someone arriving on foot.

I had spent some years discovering the region in this way, using the hit or miss approach of combining the green Michelin guide with the railway map, before I realised that I had the makings of a book which could offer something unique to its readers: a guide entirely conceived with the needs of the foreign visitor arriving by train in mind. Not only would it have clear, detailed instructions and usable local maps which showed the station, it would, where possible, give interesting routes which led from one station to another, rather than the circular route imposed by having to return to a car.

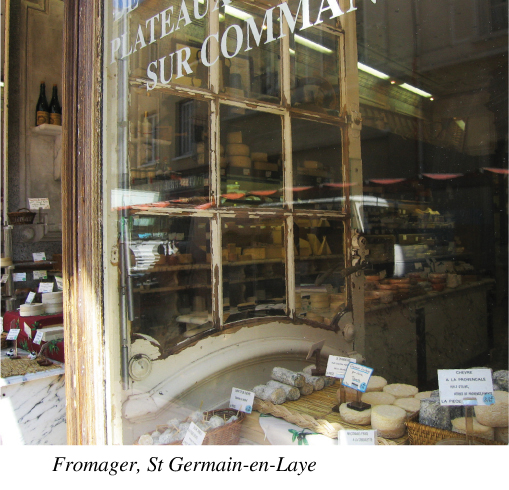

As the book took shape, so did my picture of the kind of reader I had in mind. It was no longer simply someone who did not have a car. More importantly, it was someone who was essentially curious about everything, rather than with a specialist interest in walking, architecture, gastronomy or whatever, someone who was interested in the present as well as the past, who loved the countryside and enjoyed walking, but who also liked stopping at cafs and appreciated the humbler type of restaurant where they would probably be the only foreigner. Above all, it was someone who avoided crowds and pre-packaged experience wherever possible and was happiest when exploring off the beaten track.

This kind of reader would probably not want to use a guide at all, but I felt that it would be worth their while to buy my book for two reasons. They could easily adapt the techniques I had spent years perfecting to find authentic places for themselves, and they could use my book to visit some of the little places I describe. Not only would they be the very people most likely to appreciate these, their presence in greater numbers might also help to halt the process of decline and/or creeping standardisation which is gradually taking hold. After all, Giverny now has a local bus service from the station because a few Americans first started the fashion of going there.

Next page