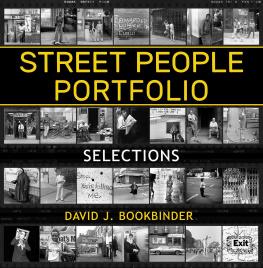

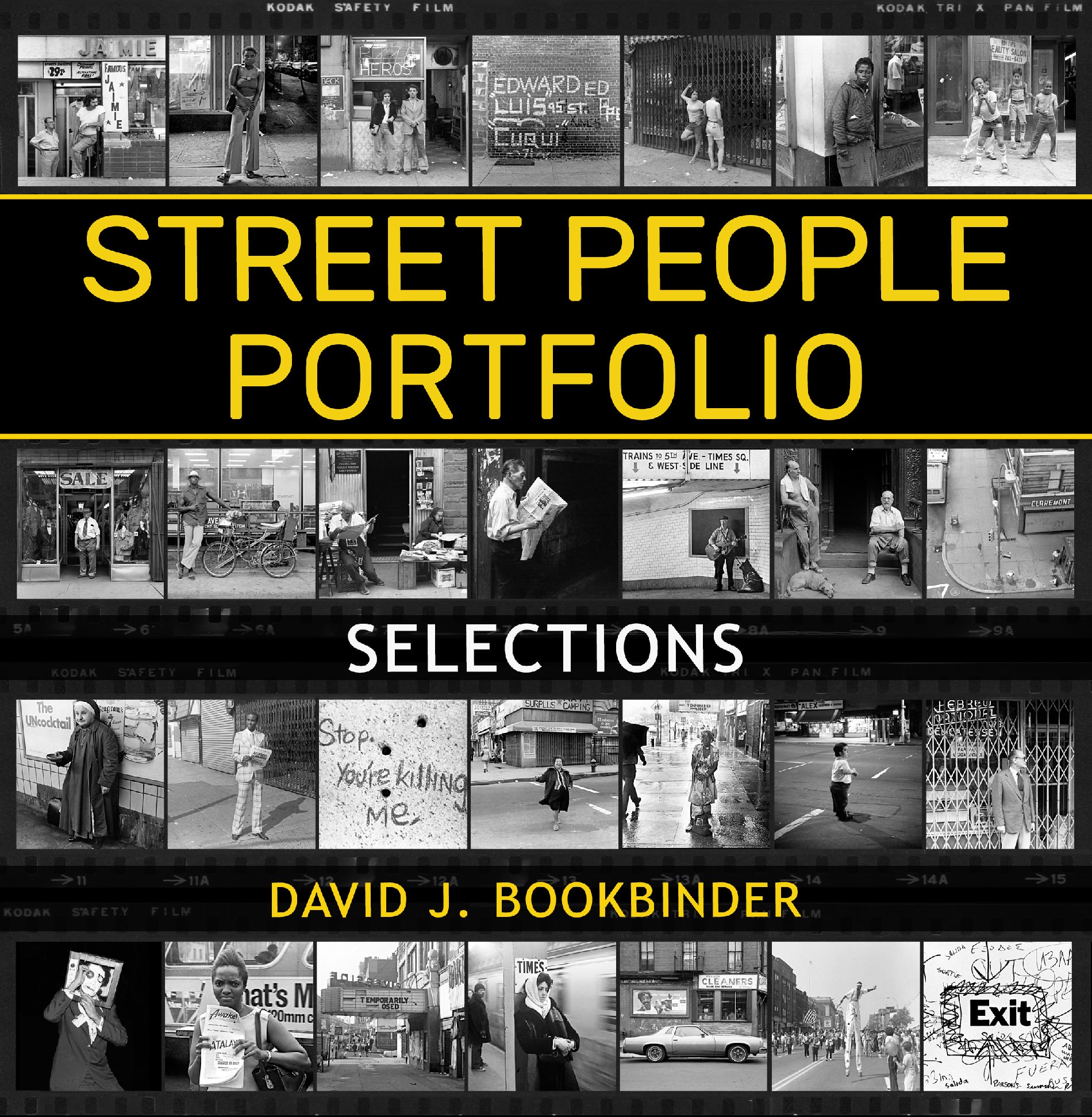

STREET PEOPLE

PORTFOLIO

SELECTIONS

DAVID J. BOOKBINDER

TRANSFORMATIONS PRESS

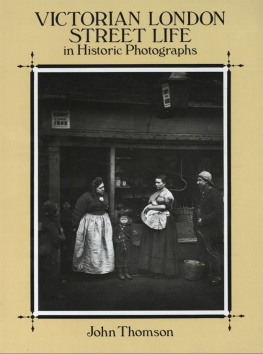

OTHER BOOKS BY DAVID J. BOOKBINDER

What Folk Music Is All About

Paths to Wholeness

The Art of Balance

52 Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas

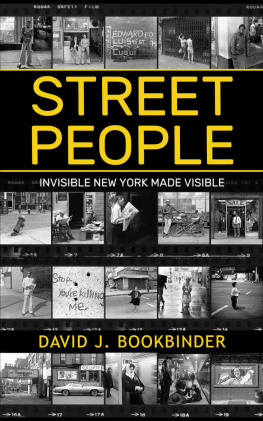

Street People

Street People Portfolio

OTHER TRANSFORMATIONS PRESS BOOKS

Metaphysical Tales

Vienna

O Amazonas Escuro

The House of Nordquist

Maison Cristina

Cotton Moon

Copyright 2022, David J. Bookbinder

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without prior written permission of the authors.

Published in Wenham, Massachusetts by Transformations Press.

Email:

Phone: +1 857-264-0312

Books: transformationspress.org

Images: phototransformations.com

Main: davidbookbinder.com

Instagram: @tranformationspress

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book contains selections from Street People Portfolio: Invisible New York Made Visual , a collection of photographs of street people and street scenes that I shot in Manhattan and Brooklyn during 1975-1979.

I hope you enjoy this glimpse into what is on the surface a very different New York City than the one you may know today.

Im grateful youve begun this journey with me. To see more images from this series, go to phototransformations.com . You can learn more about Street People Portfolio and its companion book of related stories, Street People: Invisible New York Made Visible , at Transformations Press .

INTRODUCTION

I took the photographs in this book in Manhattan and Brooklyn in 1975-1979. But the story of Street People Portfolio begins with a single image.

It was the summer of 1969, I was 18, and Id just hitch-hiked into New York City from three days of peace and love at the Woodstock music festival. This was my first visit to the city. Strolling on the Bowery, I saw human beings sprawled along the curb and lying beside buildings like so many sacks of garbage. It stunned me.

I shot this photo of a man passed out in a doorway, his arms extended like Christ on the cross.

The Bowery, 1969

That image stayed with me long after I left New York.

Fast forward six years to the summer of 1975.

At that time, New York was a mecca for artists, writers, and musicians, and a center for high fashion and commerce. It was also a place of grinding poverty and urban decay.

I lived in a cockroach-infested railroad flat on the corner of West 98th Street and Broadway, a neighborhood that was literally falling apart around me. By then Id hitch-hiked through much of the United States, and urban squalor was not new to me. New York, however, was still a shock to my system.

Much of that jolt came from its street life. I saw and interacted with people I had rarely encountered, among them prostitutes, bag ladies, derelicts, drug dealers, beggars, small-time thieves, and con artists. While most New Yorkers kept their gaze fixed ahead with eyes that warned, Dont approach me, mine went everywhere.

In the movie The Sixth Sense , Haley Joel Osment sees dead people. I saw street people. I struggled to understand this attraction. Was it their novelty? Did I identify with them? Was I a voyeur? None of these explanations rang completely true. Only years later did I realize that I was an empath and, like one tuning fork resonating with another, I felt their presence and, often, their pain. It was not empathy, however, that motivated me to photograph and write about street people. It was opportunity.

New York was perhaps the worst city in America for someone with virtually no experience in the field to begin a career in journalism. For more than a year, Id been shuffling from one short-term job to another while I wrote articles and took pictures for neighborhood newspapers, trying to get a foot in the door of the New York journalism world. Id made little headway. I lived a hand-to-mouth existence, never sure where the next meal would come from.

Throughout this period, I also explored the streets and subways of Manhattan, carrying with me an SLR Id bought in high school and a Robot Star II camera. Originally used by the Luftwaffe to record kills, this tiny German device captured square-format images on 35mm film. Its wind-up spring could actuate the shutter multiple times per second. It was the perfect street photography camera.

I saw myself as a correspondent to the middle classes, able to step into a realm invisible to most of my fellow New Yorkers and then return, I hoped, with something of value. I stopped writing newspaper stories and, released from the stricture of assignments and deadlines, I sought to record this undocumented world in my own way, on my own time. I called what I was doing slow journalism.

By the spring of 1976, Id put together a proposal for a book of photographs and stories about street people. I found an agent, and over the next year, he circulated the proposal to twenty-two New York publishers.

Initially, this was a validating, even thrilling, process, but it soon took a disappointing turn. An editor at one press said she liked the idea, but I needed to team up with a sociologist. Another editor would only consider a book about bag ladies. Yet another was interested, as he put it, in the more bizarre and eccentric inhabitants of our streets who perform their wonderful brand of street theater, which, for a lot of us, makes a city a more interesting place to be. Most of the rest returned my materials with a short note stating that although they found the idea intriguing, the subject was too downbeat to be salable. My closest brush with fame and fortune was at Scribners, the publishing home to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and their equally legendary editor, Maxwell Perkins. Perkins successor approved the project, but Charles Scribner IV vetoed it, declaring, Such a book should never be published.

My unemployment insurance was running out, my savings were almost gone, and I was a year behind schedule for a book about folk music I was contracted to write. I retreated to Brooklyns Fort Greene neighborhood, adjacent to Bedford-Stuyvesant, where, in exchange for doing renovation work, I lived rent-free.

Id come to Brooklyn to finish the music book and had figured Id leave within a year, but Fort Greene soon became home. I spoke to people on the street, played with the neighborhood kids, got to know the keepers of most of the local stores. I found myself drawn to the rich visual tapestry of Brooklyns much different street life, and I recorded what I saw.

In 1979, I left Brooklyn, eventually landing in Boston. I attended a graduate program in creative writing and resumed work on the street people project, which now encompassed my time in Brooklyn. Then life happened.