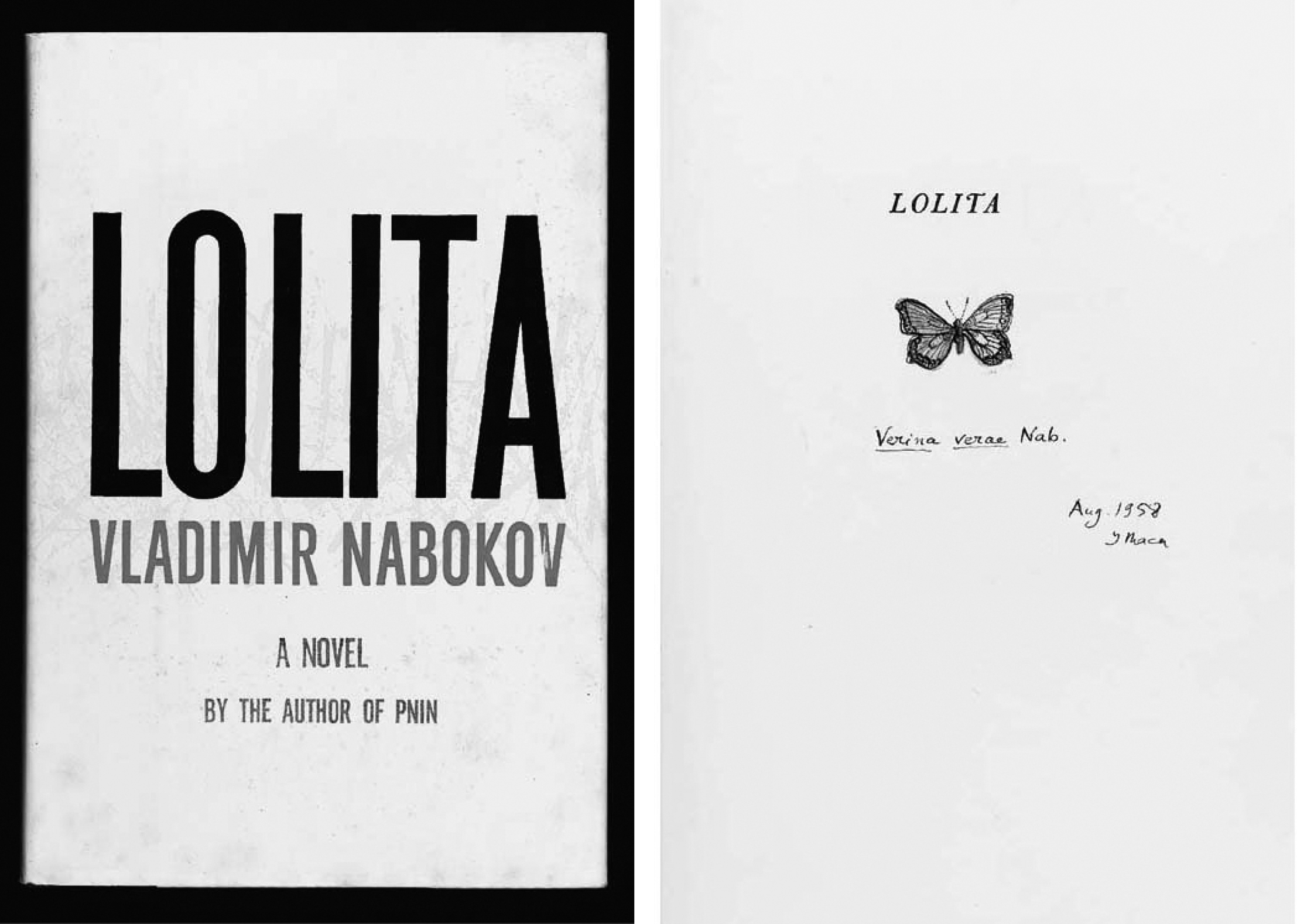

In memory of my father, Walter J. Minton, who was to me Robert Duvall in The Great Santini, Pa from Little House on the Prairie, Jack Nicholson in just about everything, and the valiant publisher of Lolita in America.

Delectatio Morosa

Lauren Groff

Lolita is a paradox: a gorgeous and venomous flying moth, a beating heart with a hole in it, a creature bursting with life and stinking of death. It is unparalleled as a profane and dirty and gorgeous mirror of America. It is also the basest of objects in what it engenders.

By engendering, of course, I do not mean the sterile sticky exertions of our glib pedophile upon his desperate love object, but rather how this most diabolical of novels has brought submerged patterns in the world to the surface and replicated them within even the innocents among us. And when I say diabolical, I mean it: there is something wholly of the devil in this book, not the red-skinned leaping horny long-tailed cloven-footed faun of folktales, but the towering Satan of John Miltons Paradise Lost. Satan, with his arrogance and pride and ambition and true blazing genius, says, after having fallen headlong, flaming into the depths of hell in his failed attempt to rout God, that the mind is its own place and in it self / can make a Heavn of Hell, a Hell of Heavn. Out of the shame and sorrow and murder of soul that Humbert Humbert perpetuates on poor child Dolores Haze, the poet in the pedophile sings a lamentation so beautiful it haunts the reader through life, makes a heaven out of the childs sheer suffering hell. These mixed states of extremity can become, in the impressionable reader, a smudged bleak shadow underlying everyday reality.

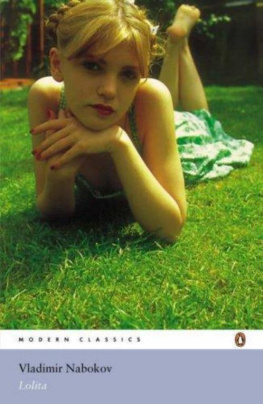

The summer I read Lolita, I turned thirteen, around Lolitas own age at the beginning of the book. I was no nymphet, if such a child truly exists in the world; I was a serious, studious, shy girl, very much still a child in my mind, skinny and nervous as a doe, although by then I had grown to my adult height. In the summers, I loved to climb a willow tree that had been struck flat at the midriff by lightning; I kept a water bottle with sugar-free Kool-Aid up there and an old My Little Pony sleeping bag, and disappeared for whole summer days to read in the cool green willow light by the lake. Sex was a vague, wordless shadow that existed somewhere outside of me, certainly not in my parents or their gross adult friends, but perhaps in the high schoolers in the far wings of the school building who blurred into one loud and seething mass in my terror of them. I was shocked by Lolita at first; and soon I began to be disturbed deep in my flesh by it. By the time I had finished it, the book had turned sex squarely in my direction and attached it to my body.

And when I looked around, I discovered that all around me, the bodies of my little friends, these girls who rode their bikes in their Umbro shorts, who did ballet in pointe shoes, who secretly tried on their aunts sparkle lip gloss, who cried when they watched The Princess Bride during sleepoversthese half-grown girlshad become in my vision unexploded bombs waiting for male desire to light their fuses.

I want to emphasize from the safety of my middle age that there was no real power in our tentative newfound status; but feeling oneself an object of attention can create the illusion of power. After all, there is a currency of attention, as well as a currency of attraction. Perhaps men had looked at us with lust before this, but I hadnt noticed or felt the attention in my body. Now I did. Now I felt strange riding alone in cars with the fathers of the children I babysat, or being out of the water in my bathing suit, though all my life Id been a competitive swimmer. I felt the eyes of men on me. I was cowed by the heat and weight of this attention. In truth, there was a part of me that also loved it, craved their eyes, their heat, their intake of breath.

Perhaps more troublesomely, as my body awoke to sex through Lolita, I felt no reciprocal heat for the boys of my age around me who shyly showed their interest. Rather I turned in my uncertain hunger toward older men in the generation between me and my parents: actors, models, Ernest Hemingway in a passport photograph taken when he was twenty-four and ripped out of The New York Times Book Review. Not incidentally, that selfsame face that looked at me fixedly in my childhood bedroom became the face Humbert Humbert wore when I thought about his novel; the dark glower of Hemingways is still exactly that of the pedophile murderer in my mind. This does color Hemingways work in strange ways for me; I find I have stopped loving even the best of his work, through this sickly association that is not his fault.

What I want to say is that the largest repercussion of having read Lolita at Lolitas age is that the desire of grown men for young girls sank into my bones as truth. There was a return desire kindled less out of hunger than out of a sort of logical reciprocity. And for the rest of my life, this desire has spoken out of me. It has been one of my deepest erotic languages, one that I unconsciously replicated in a great deal of my own written work.

For instance, in my first completed draft of a novel, one that would never be published, there is a teenage girl who wakes up one day with no mouth and no hands. She begins to have a secret sexual affair with her mothers boyfriend, a man in his thirties.

In my second completed draft of a novel, another that would never be published, I wrote the story of Ablard and Hlose as a contemporary love story, somewhat ridiculously in a Scientology skyscraper; a fourteen-year-old girl and a man of thirty who begins as her tutor and becomes her lover.

I abandoned these apprentice novels as they deserved to be abandoned. I wrote two others, which I also abandoned. I went to graduate school and began to write short stories. In my first workshop as an MFA student, I wrote my first story that was accepted for publication, L. DeBard and Aliette. I used the Ablard and Hlose myth again. This time, the girl is sixteen years old and her legs have weakened from polio. A tutor is hired by the girls father to train her body back to full use again by teaching her to swim. It is also the time of the 1918 influenza epidemic. Despite the awkward premise, it came together as a story in a way none of my other stories ever had up to that point.

This was the way I wrote protagonists first sexual encounter, in a pool:

Aliettes cheeks grow plump, and her legs regain many of their muscles. By May, L. is being driven crazy by the touches, leg sliding against leg, arm to knee, foot sliding silky across his shoulder. He immerses himself in a cold-water tub, like a racehorse, before coming out to greet her.

Their flirtation slips. Dawn is pinkening in the clerestory window, and L. is lifting Aliettes arm above the water to show her the angle of the most efficient stroke, when his torso brushes against hers, and stays. He looks at the dozing Rosalind. Then he lifts Aliette from the water and carries her to the mens room.

As she stands, leaning against the smooth tile wall and shivering slightly, he slides her suit from her shoulders and slips it down. To anyone else, she would be a skinny, slightly feral-looking little girl, but he sees the heart-shaped lips, the pulse thrumming in her neck, the way she bares her body bravely, arms down, palms turned out, watching him. He bends to kiss her. She smells of chlorine, lilacs, warm milk. He lifts her and leans her against the wall.