Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing,

243 5 th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS16CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dakers, Diane.

Title: American life and best sellers from the Catcher in the Rye to the Hunger Games / Diane Dakers. Description: New York : Cavendish Square, 2017. | Series: Pop culture | Includes index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781502619815 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502619822 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: American literature--20th century. | American literature--21st century. |

Popular culture--United States--20th century |Popular culture--United States--21st century.

Classification: LCC PS509.U52 D37 2017 | DDC 810.8'006--dc23

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Kelly Spence Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger Art Director: Jeffrey Talbot Designer: Jessica Nevins Production Assistant: Karol Szymczuk Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images, cover background, Araya Diaz/WireImage/Getty Images, cover; Yellow Dog Productions/Digital Vision/Getty Images, 4; H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images, 9; Ben Stansall/AFP/Getty Images, 11; MANDEL NGAN/ AFP/Getty Images, 14; Walter Bibikow/Danita DelimontPhotography/Newscom, 16; John F. Kennedy Library/Archive Photos/Getty Images, 20; Mel Finkelstein/NY Daily News Archive /Getty Images, 22; Stanley Sherman/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 23; New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Albertin, Walter, photographer./ Library of Congress/File:Martin Luther King Jr NYWTS 4.jpg/Wikimedia Commons, 25; Steve Northup/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images, 29; DWD-Media/Alamy Stock Photo, 32; Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo, 38; INTERFOTO/Alamy Stock Photo, 40; Kenzo Tribouillard/AFP/Getty Images, 47; Charles Knoblock/

AP Images; 49; Eugene Gebhardt/The Image Bank/Getty Images, 52; 20th CENTURY FOX/Ronald Grant Archive Alamy Stock Photo, 54; Lynne Sutherland/Alamy Stock Photo, 57; Joe McNally/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 60; Kaveh Kazemi/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 65; Dan Loh/AP Images, 67; ZUMA Press''Inc/Alamy Stock Photo,

70; Fred Duval/FilmMagic/Getty Images, 73; Jose Luis Magana/AP Images; 76; AF archive/Alamy Stock Photo, 81;

Greg Sorber/Albuquerque Journal/ZUMAPRESS.com, 83; by Alex Wong/Newsmakers/Getty Images, 87; Travel Pictures/Alamy Stock Photo, 89; Charles Sykes/Invision/AP Images, 92; shahfarshid/iStock/Thinkstock.com, 97.

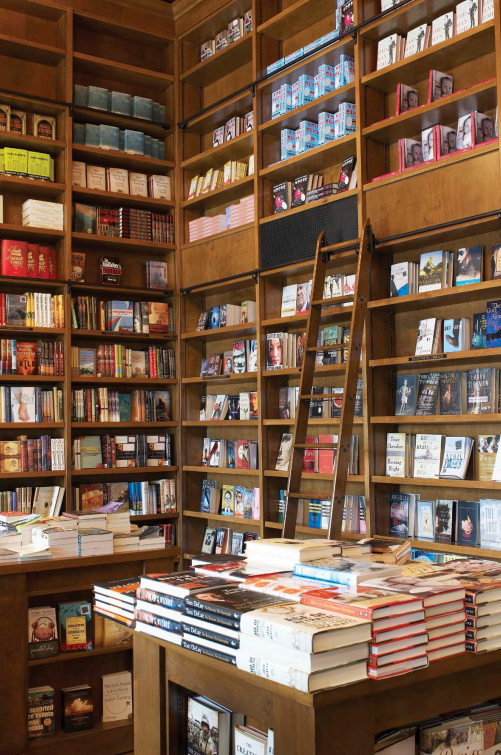

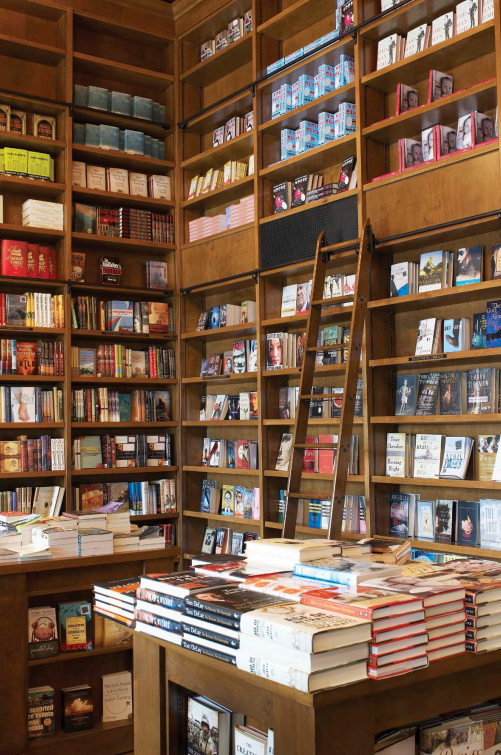

Opposite: For hundreds of years, readers have been thrilled, frightened, educated, and entertained by the books they read. The form that books take may change through the centuries, but as long as there are writers, there will be books and people who read them.

WRITERS HAVE BEEN PUTTING THEIR thoughts on paper for centuries. In the beginning, every copy of every book was handwritten. After the printing press was invented in the 1400s, publishers could produce books in larger quantities. Books became more widely available, but only the educated classes of society knew how to read. So books weren't huge sellers at the time.

As the centuries progressed, and individuals in all walks of life became educated, books became more and more popular.

At the same time, new technologies made it easier and cheaper to mass-produce books. First, it was the printing press. (In the United States, the first books were printed in the 1600s.) Later, writers started using typewriters and word processers. When desktop publishing was invented in the mid-1980s, anyone with a computer could suddenly design and produce books. Today, we have digital, Internet, and e-book technology.

With the invention of e-readers in the late 1990s, many people predicted the end of the book business as we knew it. Devotees of hardcovers and paperbacks feared the end of libraries and bookstores.

In previous generations, technophobes feared radio would be the death of the newspaper, TV would kill the movie industry, and the Internet would spell the end of television. None of these have come to pass just yetnor has the death of the real book.

Over the centuries, books have helped little children fall asleep at night. They have kept soldiers sane on battlefields during wartime. And they have helped commuters pass the hours on trains, buses, and airplanes.

Books have reflected the politics, society, and culture in which we live. Printed stories have thrilled, entertained, educated, and frightened readers for generations. In one form or another, they will continue to do so. As long as there are books, there will be readers.

And as long as there are readers, there will also be bestseller lists to tell readers what other readers are reading.

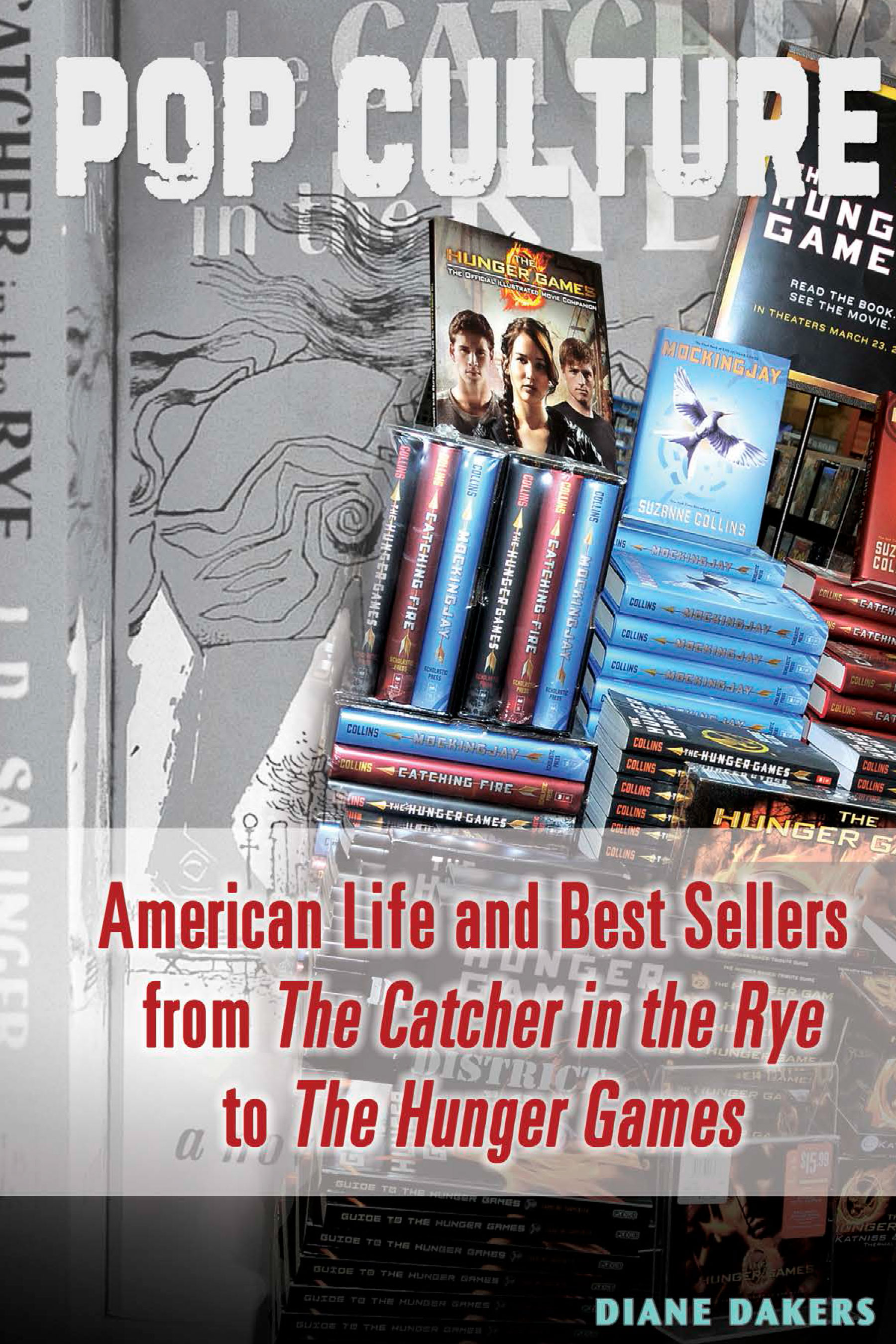

Early twentieth-century best-seller lists simply tallied the top-selling books in local bookstores. Now, they also include online sales. Books that reach the top spots on best-seller lists become must-reads of the day. They are the books people talk about. They are often the books that are made into movies. And occasionally (hint: Harry Potter), they change the direction of cultural trends of the time.

IN THE 1950S, AMERICAN SOCIETY SUFFERED what some might call an identity crisis.

On one hand was a sense of optimism. World War II (1939-1945) was overand the good guys had won! After a decade of darkness, families had been reunited, and life had returned to normal. Men who fought overseas returned to their jobs. Women who worked during the war returned to homemaking. Couples raised large families, bought new cars, and moved to the suburbs.

A fabulous new inventionthe televisionchanged the way Americans viewed their world. By the end of the decade, almost every home had one. TV sets bombarded viewers with advertisements for all the luxurious things they could now afford to buy.