Sport goes on and on, you see. You have to run on the spot to keep up. Events just keep on coming: moreover they keep coming in exactly the same order, year after year, which is sensible, but also a bit depressing if the sporting calendars rigid cycle dictates your actual life.

Lynne Truss in Get Her Off The Pitch!

How Sport Took Over My Life

In the above quote, Truss is explaining why, after four years, she had had enough of being a sports correspondent for The Times. Im sure shes right about sport, but gardening, if anything, is even worse. At least when Spurs play Chelsea this year, the result may be different from last year; the exact score is almost certain to be. But its hard to persuade yourself that planting your runner beans or pruning your wisteria this year will feel much different from the same job last year. And gardening journalism can feel the same; once youve written one column on what to do in June, do you ever need to write another one?

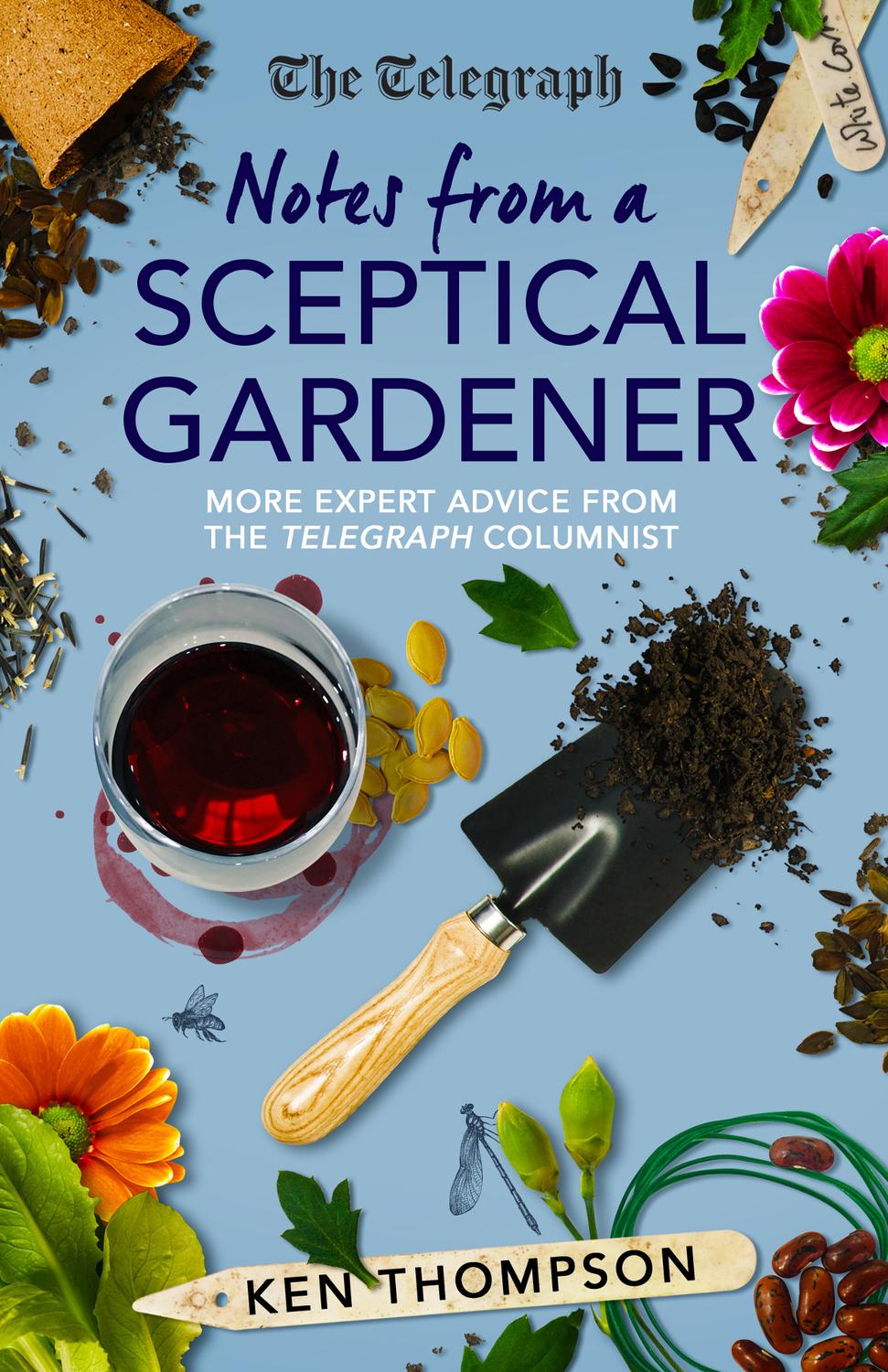

Thus it was, ten years ago, that I set out to write a different kind of gardening column. One that addressed questions with no obvious answer or worse still, answers xiv that are all too obvious, but still turn out to be wrong. One that asked questions that no one in their right mind had even bothered to ask before, such as whether birds understand speed limits, whether foxes really are getting bigger, what (if anything) the plants on the Duchess of Sussexs new coat of arms tell us, and just what are plants anyway? Occasionally, I even write something useful, such as how to make your own slug gel, the best way to stop the needles falling off your Christmas tree, or the best plants to persuade someone to buy your house.

My indispensable partner in this enterprise was, and still is, Joanna Fortnam, gardening editor of The Daily Telegraph. Joanna and I, despite actually meeting only rarely, manage to see eye to eye on the need for a column like mine grit in the gardening oyster. Remarkably, ten years on, there still seems to be an inexhaustible supply of fresh stuff to ramble on about, and even more remarkably, neither Joanna nor the readers of the Telegraph seem to have tired of those ramblings.

After about five years, the columns available at the time were collected in the book The Sceptical Gardener. And now, in what seems like no time at all, here we are again, with a completely fresh collection. As before, I have not attempted to update them. Most dont need it, and in any case the updating itself would soon be out of date. Here and there, I have added a brief footnote that explains where we are xv now (in late 2019). In even fewer cases, a footnote clarifies a topical reference that isnt obvious from the context. Otherwise, the columns are reproduced here in exactly the form in which they were originally written. A handful of columns failed, for one reason or another, to appear in the Telegraph (Joanna and I dont agree about everything), but it seems a shame to waste them (especially as one or two are personal favourites), so theyre here too.

A huge thank you to Joanna, of course, for putting up with me all this time. And also to Duncan Heath at Icon Books, who not only took a chance on publishing the first collection, but was happy to come back for more. To everyone else at Icon, including Ellen Conlon for her work on the text, Marie Doherty for her typesetting, Lisa Horton for her lovely cover design, and Ruth Killick for publicity, and to Michael Stenz at the Telegraph, for seeing the project through to fruition. Many thanks as always to my wife Pat for putting up with me while I write. Finally, thanks to you, the reader. If these columns are new to you, I hope you like them, and if youve read them before, I hope you enjoy them all over again. I certainly enjoyed writing them. xvi

The fritillarys chequered past

Reading a magazine article recently, I was surprised to find marsh fritillary included among a list of plants. I suppose if you were a plant person, familiar with the common snakes head and other fritillaries of the botanical sort, you might easily assume a marsh fritillary was a plant. In fact, of course, the marsh fritillary is a butterfly, and there are several other fritillary butterflies. Which set me wondering: why are the plants and the butterflies both called fritillaries?

The first thing to notice is that the butterflies and the snakes head fritillary (but not most other plant fritillaries) share a rather similar chequered pattern, black and orange in the butterflies and various shades of purple in the plant. There is a general consensus, shared by Wikipedia and my Shorter Oxford Dictionary, that the name refers to this pattern, and comes from the Latin fritillus, meaning dice-box. But what exactly is a fritillus, and what has it got to do with a chequered pattern?

Well, the Romans were great gamblers, and went to a lot of trouble to prevent players cheating when throwing dice. The simplest solution was the fritillus, which was more of a dice-cup than a dice-box usually a fairly plain cylindrical container in which dice were shaken before being thrown. Often they had ridges or grooves on the inside to help to agitate the dice and further prevent any attempt to interfere with a fair throw.

But this is where things get complicated, because we have several fritilli recovered from Roman sites, and theres nothing remotely chequered about any of them. Maybe the answer is the pyrgus, or dice tower, the ultimate anti-cheating device. A pyrgus, which removed the human element entirely, was a square tower, open at the top. Dice are thrown into the top and descend past a series of baffles, eventually leaving the tower at the bottom, tumbling down a short staircase which mixes them up even more. As long as the dice are fair, the pyrgus completely prevents cheating.

OK, youre thinking, so what? Well, the dice tower had perforated lattice-work sides, probably to allow the players to see the dice inside, and make sure that the dice that left at the bottom were the same as the ones that went in the top. Overkill, you may think, but it looks like the Romans really did have a big problem with people cheating at dice. Crucially, this lattice pattern looks a bit like the chequered pattern of a fritillary, so maybe just maybe this is where the name comes from.