Speeches & Writings of

KATHERINE PATERSON

National Ambassador for Young People's Literature

Clarion Books * Houghton Mifflin Harcourt * Boston New York

Contents

Heart in Hiding:

T HE ART AND CRAFT OF WRITING FOR CHILDREN

BOMC/N EW Y ORK P UBLIC L IBRARY

Heart in Hiding: T HE ART AND CRAFT OF WRITING FOR CHILDREN

BOMC/N EW Y ORK P UBLIC L IBRARY

February 15, 1989

Soli Deo Gloria

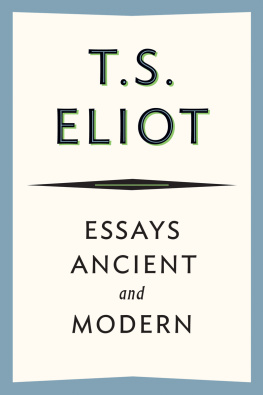

I WAS twenty years old. I remember how hot the room seemed, though it had to have been January, so it was the radiators that made it uncomfortable. It was the first day in a course entitled Nineteenth-Century English Literature. I don't know where I was when we did eighteenth-centuryasleep, perhaps. At any rate, in the fall semester I had revisited the august Milton and fallen in love with John Donne and was sure that nothing of any worth had happened in English lit. since the close of the seventeenth century. Nineteenth-Century was a seminar course, and each of us was to do a paper. The room was hot, and I was sleepy. (Are college students always sleepy?) So when my turn came to say what writer I'd selected, I racked my brain for anyone whom I could remember that might have been born English in that boring century and said at last "Kipling," having been read the Just-So Stories on my mother's lap.

"Katherine," I heard Dr. Winship saying, "you don't want to write on Kipling. You want to write on Gerard Manley Hopkins." I woke up. How could I want to write on Gerard Manley Hopkins? It was the first time in my life that I had ever heard the name, but Dr. Winship said I wanted to write about this person, and in the two and a half years that I had known Dr. Winship I had learned that he generally knew what he was talking about. So on the paper beside my name, I obediently wrote down Gerard Manley Hopkins, without knowing whether to put an "e" in the Manley or not.

That afternoon I went to the library to meet the object of this arranged marriage. I remember all too well the first poem I read. It was "The Windhover."

I caught this morning morning's minion, king

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy!...

I would like to tell you tonight that my first encounter with Gerard Manley Hopkins filled me with ecstasy. Actually, it was more like sheer panic.

If you've read The Great Gilly Hopkins, you'll remember the scene when Gilly, who thinks of herself as a terrific reader, arrogantly opens The Oxford Book of English Verse to read aloud to the old man who lives next door and stumbles into

Sumer is icumen in,

Lhude sing cuccu!

Groweth sed, and bloweth med,

And springth the wude nu

Sing cuccu!

Cuckoo was right. "Wait a minute," [Gilly]

muttered, turning the page.

Bytuene Mershe ant Averil...

She looked quickly at the next.

Lenten ys come with love to toune,...

And the next

Ichot a burde in boure bryht,

That fully semly is on syht,...

She slammed the book shut. They were obviously trying to play a trick on her. Make her seem stupid. See, there was Mr. Randolph giggling to himself. "It's not in English!" she yelled. "You're just trying to make a fool of me."

"The Windhover" didn't seem to be in any English that I knew, but I also knew that Dr. Winship was not trying to make a fool of me. I may well have needed taking down a peg or two, but he wasn't that kind of professor. He had said that I would want to do Hopkins. I ground my molars and squinted my eyes. Dr. Winship not only thought that I should be able to understand this mad poet, but thought I would like him. So, by golly, I would find out why or die in the attempt.

The first thing I did was fetch a dictionary and look up the meaning of every word in the poem that I was fuzzy on, beginning with the word windhover. When I had firmly in mind the literal meaning of every word, I began to read the poem over and over again. At last, in desperation, I read it aloud. The rest, as they say, is history. I went on to write the paper. The next year I did my undergraduate thesis on Hopkins, and through the thirty-six years since that sleepy January morning, I have gone back again and again to my slender volume of Hopkins's poetry for inspiration, for nourishment, for comfort.

Gilly Hopkins is, of course, Gerard Manley's namesake, though I wasn't aware of the relationship until well after the book was published.

I think of my first reading of "The Windhover" whenever a teacher, a parent, or a librarian begins to talk about allowing children to make their own reading choices. I believe in freedom of choice as much as anyone, but, friends, the young don't know the rich variety of choices that are available. Someone whom they trust must be wise and bold enough to hand them something they would never have known to choose, or upon initial meeting would immediately reject, and say with authority: "This is especially for you."

I remember the day I met Gerard Manley Hopkins as a pivotal point in my life. It would be years before I would think of myself as a writer, and though from time to time I try to write poetry, I have never thought of myself as a poet. But something happened to me that day that I find hard to articulate. I learned something about how language works on the mind and the heart and the ear.

Many of you have heard me speak before, and I apologize for repeating myself. It's your own fault. You would come hear me again. But you can read your bibliographies while I talk to the rest of the group about the kokoro. Kokoro is the Japanese word for "heart." But it's not simply heart as the seat of the emotions; the kokoro is also the seat of the intellect. The mind/heart, if you will. Thus the Sino-Japanese character for idea combines the ideograph for the word sound with the ideograph for kokoro for "mind/heart." So an idea is a sound from the heart. If you want to write the character that means "to imagine," you make the ideograph for tree, then you put an eye spying out from behind the tree, then below the eye spying out from behind the tree you again put kokoro, or "heart." Which is why, of course, I named a book about reading and writing children's books The Spying Heart.

Now all of this is to try to explain what happened to me when I began reading Gerard Manley Hopkins. As I read "The Windhover" aloud, something happened in my heart/mind, my kokoro, that I truly understood but that I was incapable of articulating in an intellectual, abstract fashion.

In "The Windhover," Hopkins says:

My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

My heart in hidingmy kokorostirred when reading Hopkins in a way it had almost never done except when hearing certain passages inthe King James Bible.

Hopkins himself explained to me what writing for children was all about in his poem "Spring and Fall: To a Young Child."

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow's springs are the same.

Next page