Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

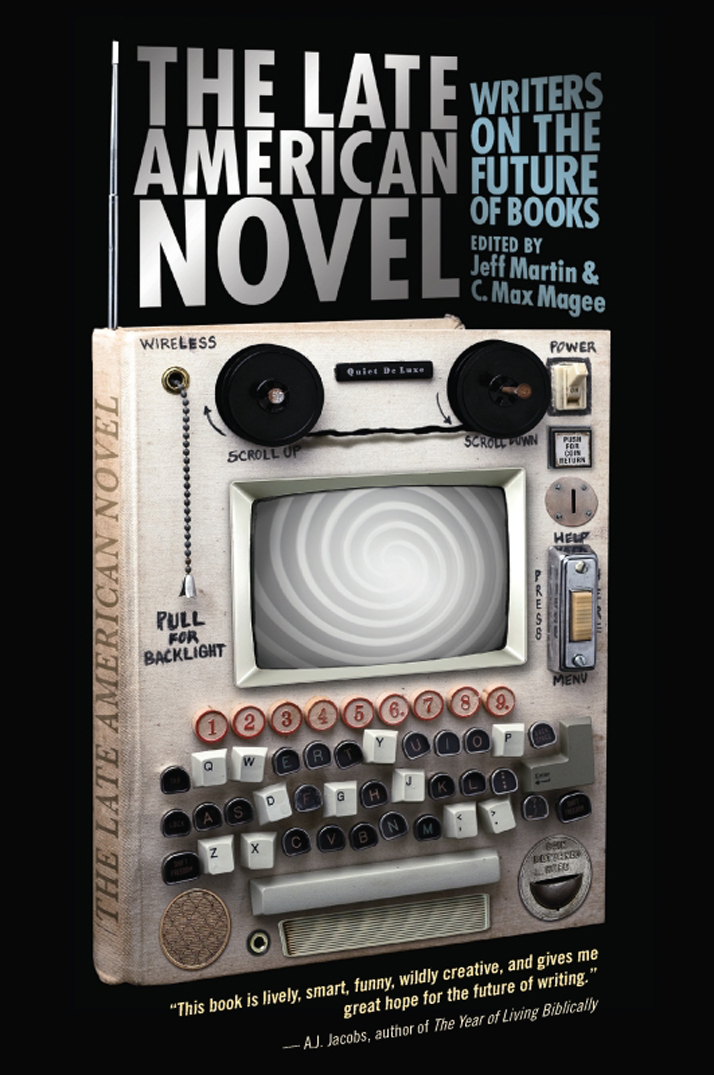

It doesnt matter how good or bad the product is, the fact is that people dont read anymore.

Steve Jobs

If serious reading dwindles to near nothingness, it will probably mean that the thing were talking about when we use the word identity has reached an end.

Don DeLillo

With my eyes closed, I would touch a familiar book and draw its fragrance deep inside me. This was enough to make me happy.

Haruki Murakami

INTRODUCTION

Jeff Martin and C. Max Magee

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously remarked, There are no second acts in American lives. While true in his specific case and dramatic in that Lost Generation sort of way, this statement has been proven wrong time and again. From Richard Nixon to John Travolta, American life is filled to the brim with second acts. Some lucky people even manage a third or fourth (Cher, anyone?). But this phenomenon isnt limited to people; we see it all around us. The LP was declared dead years ago, yet more and more bands are putting new material out on vinyl. The Boomers are dusting off their old turntables and their grandkids are buying new ones. Whats out of fashion becomes retro, then goes vintage, and then comes back into fashion again. It all comes down to one word: reinvention. The word itself conjures up images as evocative of the stereotypical American dream as apple pie, Aaron Copland, or Chevrolet. In America, you can arrive a pauper and leave a prince, or at the very least own a home with a low interest rate and a TV that gets 300 channels. Its been called the Land of Opportunity for quite some time, but a more apt description would be the Land of Reinvention.

Our media consumption over the past century or so looks like a Darwinian chart, a rapid evolution from gears and cranks to miniaturized Space Age sleekness. In that short time weve gone from phonographs to iPods, from 16mm reels of film to Blu-ray discs. But in that time, one format has remained virtually unchanged until recently: the book.

The written words last big format change turned out to be a pretty big deal, fomenting revolutions and laying the groundwork for modern civil society, the scientific revolution, and modernity itself. Gutenbergs big coup sent shockwaves through palace halls across Europe (though, it should be noted, moveable type printing had been invented earlier in Asia) and soon reverberated around the globe. With the invention of the bound, printed, mass-produced book, medieval scribes found themselves left with an obsolete skill set. Latin and Greek faded as the linguae francae of the learned classes when printers sprang up and produced books in the local vernacular. Never before had shared knowledge been so accessible to so many. So alien and threatening to the established monopolies of knowledge, power, and morality were these insidious new devices that they set off a struggle that has raged on and on and on, from early sixteenth-century France, when King Francis I briefly made book printing a capital offenceHis Royal Highness reacting to the new technologys facility for inciting religious schismto the bookbanning brigades picketing your local library today.

The proliferation of printed books also led to developments like the standardized spelling of the words youll read in these pagesbecause who cared about spelling previously, when reading was a rarity?and a greater awareness of the rules of grammar, which are nearly impossible to codify without a visual and intellectual understanding of language. The impact of the mechanical reproduction of books, though it did not register as lightning fast as the technological change of today, was nothing short of the remaking of civilization. And even as other media have followed the book and usurped its position at the center of cultural exchange, it still seems vital for us as a species to consider what a change in the essential form of the book might mean for our future.

Because into this heady mix has come something as new and potentially paradigm-shifting as those first German Bibles. With the advent of e-readers, near infinite data storage capability, and a shift to a more sustainable and digitized culture, a sea change is upon us. Will books survive? And in what form? Can you really say youre reading a book without holding one in your hands? These and other similar questions have shaped this collection.

We dont claim to know what will happen to the traditional bound and printed book, but theres no shortage of discussion about the road that lies ahead. We wanted to hear from some of todays most promising literary voices, to find out if they are optimistic, apathetic, or just scared shitless. And as might be expected, there is no general consensus. Some of the writers included in this anthology have devised ingenious schemes and strategies, seeking to mark out future spaces in which books will survive and even thrive. Others expect future generations to encounter dystopian literary landscapes, where the merging of media and digital technology leaves books unrecognizable and somehow diminished in the eyes of readers. Some offer confident prognostications about literatures future in this increasingly digital age, while others candidly admit they have no idea what lies ahead.

So if youre reading these words on a device that requires batteries, charge it up before you get too deep. If youre staring at a dog-eared paperback, nows the time to get yourself a cup of coffee.

Here we go.

THE FUTURE OF PAPER

Rivka Galchen

The avian flu morphs yet again. (Those flu viruses are so adept at evolving.) The pigs had the flu, as did the chickens, the Canadians, the zebra mussels, the horseshoe crabs, maybe even the honeybees (we still dont know as the paperwork hasnt been filed yet). Then the flu spread from live cranes to folded paper cranes, and from there to Laffy Taffy wrappers (some argue that the flu hit the candy wrappers before the cranes, that there was a mix-up in paper/crane taxonomy), and then back to the paper cranes more virulently. But somehow no one was too worried, not then; maybe everyone was even secretly pleased because paper cranes have long seemed hackneyed and sentimental... From there the virus morphed to infect broadsheets and then pamphlets and then magazines and then books. (Yes, debate exists there too, about the order, about who infected whom, but I for one suspect that the tuberculosis hit all paper at once, that we only learned about the origami and the candy wrappers first because we lived more closely with them than with our books and magazines.)

But once the paper started coughing, sputtering blood, acquiring jaundice, etc... once that happenedtruth be told, we hadnt even liked paper that much beforewe realized that, like the passenger pigeon and the woolly mammoth and electric blue, we were going to miss paper when it was gone. The dying look so good. Doc Holliday is a heartthrob. It was good for books to suddenly seem more like Doc Holliday and less like a well-intentioned middle school teacher in a beige vest. We had all been happily neglecting the books; then they became, in their death throes, as Hollywood-compelling, as gala event-able, as, say, AIDS research, or the environment. Which isnt to say we were able to do much, but we sure did documentin digital mediaourselves not doing it.