would not have been possible.

I N S ENEGAL, when someone dies, you say that his or her library has burned.

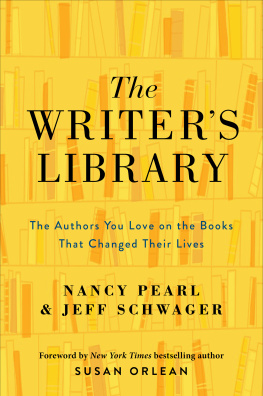

I dont know how I came across this phrase, or what I had googled that led me to it, but as soon as I saw it, I was intrigued, so I scribbled it on an index card and hung it on the wall beside my desk. At the time, I was in the middle of writing about the largest library fire in American history, which occurred in 1986 and nearly destroyed the Los Angeles Central Library. The afternoon I stumbled on the phrase, I was, as usual, puzzling over the fundamentals of my subject. Why did I carewhy should anyone careabout a library burning? If books are just paper and ink, and in the modern era can be reproduced easily, why do we feel the loss of even one book so acutely? Why do books seem so human, so personal? What makes them feel almost alive, as if a book is a person sitting right beside us, whispering a marvelous story in our ear? These are the same questions that propelled Nancy Pearl and Jeff Schwager to undertake The Writers Library, asking writers what books whispered most persistently in their ears.

The Senegalese phrase puzzled me almost as much as it fascinated me. Of course, I love books. The books that have meant the most to me have quite literally changed me. But I still had trouble picturing myself as a human library.

Furthermore, I didnt see what death and a library fire had in common. And yet something about the phrase stuck with me, nagged at me. Day after day, I stared at that index card and tried to figure out what it meant. I read everything that threaded a direct line from bound manuscript to human existence. My favorite observation came from John Milton, who declared in 1868 that books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are. I certainly understood that potency of life: I couldnt bear to throw a book out, even if it was falling apart, and I felt that each book on my shelves had a radiant presence, like a familiar friend. Indeed, books have the capacity to seem more alive than any other inanimate object. They inflect the way we feel and think. For writers, especially, the love of a particular book can be seminal, as Nancy and Jeff learn. For Jonathan Lethem one such book is James Baldwins Another Country. For Maaza Mengiste, The Corpse Washer by Sinan Antoon shook her to her core. For Andrew Sean Greer, Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin lives and breathes. For an eight-year-old Donna Tartt, her grandmother reading her Charles Dickenss Oliver Twist aloud opened her mind to the full force of literature.

But do we in some way resemble books? Do we embody the books weve read throughout our lives? That seemed the harder part of the equation. In the end, the answer made itself clear to me in a heartbreaking way. My mother was responsible for introducing me to the love of books and libraries, and she made sure I was as besotted with them as she was. When I was a child, she took me to the library several times a week, and she treated those visits as a sort of hallowed ritual, and the books we borrowed were as precious as relics. She dreamed of being a librarian. In fact, almost every time we drove home from the library, she punctuated the trip with a long sigh and the announcement that if she could have chosen any profession in the world, she would have been a librarian. The library suited her perfectly, because unlike some avid readers, she didnt yearn to own scores of books. She simply loved consuming them, and she believed that each book she read became part of her, patched into her consciousness. Owning the physical copy of the book wasnt necessary at all.

I knew my mother took pride in the fact that she had indoctrinated me with library love, even though I hadnt ended up fulfilling her dream of becoming a librarian. We often talked about what we were reading, and reminisced about our trips to the library. Then she was diagnosed with dementia. Every time I visited her, it was as if chunks of her memory had been pried loose and fallen away. It was as if the ideas and memories and daydreams and notions that made up who she was were like individual volumes, and over time, they were being pulled out of her internal library and discarded. To borrow the Senegalese phrase, it was as if her library was burningthe essence of who she was and what she remembered, all stored in tidy rows in her mind, was vanishing. Among what was lost were all the stored memories of every book she had read and internalized, gathered over decades, savored and synthesized, now gone, gone, gone.

Never had it been more vividly illustrated to me that we are indeed living libraries. Our consciousness is a soaring shelf of thoughts and recollections, facts and fantasies, and of course, the scores of books weve read that have become an almost cellular part of who we are. In this sorrowful moment of losing my mother, I came to understand that the equation of the human mind and books was correct. At last, I understood how much we all are our books. Their meaning to us doesnt end when we close the last page. What we glean from them alters us permanently; it becomes part of who we are for as long as we live. There is joy in appreciating how much our books are truly aliveon our shelves, on our desks, but most of all in our minds.

The Writers Library demonstrates how for writers, especially, the books we have read and loved and adored are integral to every atom of our beings. The first books that beguile us, the sentences that inspire us, the characters we feel we know as well as our best friendsNancy and Jeff show that these make up who we are and what we try to create so that the next readers can fall in love with books just as deeply as we did.

T HIS BOOK never would have been written had we not met in the spring of 2017, when Jeff was curating an exhibit for the Washington State Jewish Historical Society honoring twenty exceptional women who have made their mark in the state, including Nancy. During our interview for that project, we saw something we liked in each other: a similarity in background, each of us raised in a secular Jewish household whose guiding principles were based on empirical facts, not theology; a love of books and authors, characters and language, and most of all good stories; a shared sense of humor that helped us get through the days of our lives, particularly the darkening days of twenty-first century America; and a basic enjoyment of intelligent conversation. Neither of us would have written this book alone. Without each to spur the other on, we would have stayed home and read.

Having decided to collaborate on a book of interviews with authors, we chose to focus on an essential question that didnt seem, to us, to be adequately, or at least exhaustively, covered in the many interviews each of our subjects participates in every time they publish a new book. That question was, How does the practice of reading inform the life of a writer? While, inevitably, our interviews would drift into the subject of our subjects own work, our primary goal was to get them talking about other writers and other books. Did they come from reading households? What were the first books they read? What books made them realize they wanted to become writers themselves? What did they read for pleasure? What did they read for something more than pleasureknowledge, instruction, comfort, sustenance? The questions came fast and clearyoull see them all as you read these interviews. But they all boil down to the same thing: Why do you read, and how does reading help you write?