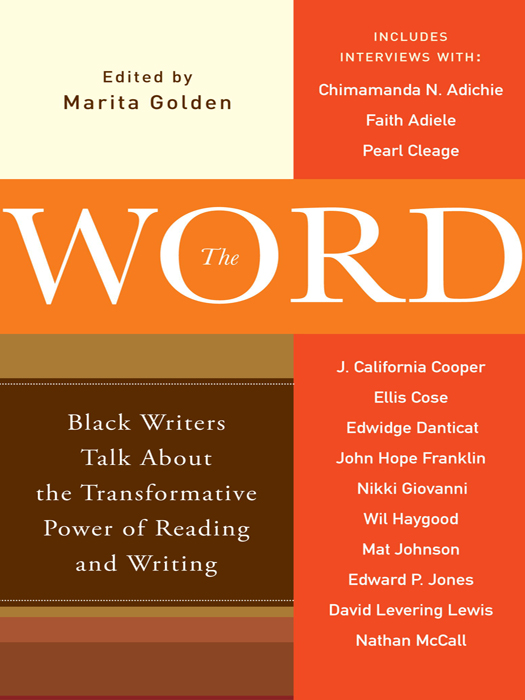

Copyright 2011 by Marita Golden

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Broadway Paperbacks, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Broadway Paperbacks and its logo, a letter B bisected on the diagonal, are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The word : Black writers talk about the transformative power of reading and writing : interviews / edited and with an introduction by Marita Golden.

p. cm.

1. American literatureAfrican American authors. 2. African AmericansLiterary collections. 3. African AmericansIntellectual life. 4. African American authorsInterviews. 5. ReadingUnited States. 6. AuthorshipUnited States. I. Golden, Marita.

PS153.N5W67 2010

810.80896073dc22

2010003391

eISBN: 978-0-307-72077-1

Cover design by Nupoor Gordon

v3.1

To Clyde McElevene, my friend and bibliophile par excellence, who has generously nurtured my love of reading and books, and whose passion for the word is singular and inspiring. Thank you for making me a better reader, writer, and thinker.

Contents

Lets imagine theres an earthquake tomorrow in the average university town. If only two buildings remained intact at the end of the earthquake, what would they have to be in order to rebuild everything that had been lost? Number one would be the medical building, because you need that to help people survive, to heal injuries and sickness. The other building would be the library. All the other buildings are contained in that one. Reading is at the center of our lives. Without the library you have no civilization.

R AY B RADBURY

If you open up scripture, the Gospel according to John starts: In the beginning was the Word. Although this has a very particular meaning in Scripture, more broadly what it speaks to is the critical importance of language, of writing, of reading, of communication, of books as a means of transmitting culture and binding us together as a people.

B ARACK O BAMA , then U.S. senator from Illinois speaking before the annual conference of the American Library Association, June 23, 2005

Introduction

T HIS IS A book about stories. An extended meditation in a choir of voices, all remembering and recounting how stories defined and made possible creativity, community, and a meaningful life. Reading and writing are the twin pillars of modern civilization, endeavors that exist as a kind of oxygen necessary for the transformation of both individuals and societies. Global in their potential impact, reading and writing are, however, among the most intimate, even secretive, acts we can perform.

Both are so deeply woven into our understanding of communication and reflection that we take them for granted, often unaware of the myriad gifts they render unto us. From both acts we gain self-knowledge, empathy, catharsis, information, and answers to questions we had not yet felt trembling on the margins of our dreams. We are launched into our next adventure, be it a journey to another land or a new job, because a book told us we could do it. We give our fantasies a dry run on the pages of a diary or in the words of fictional characters, each single word we write drawing us closer to what words have suddenly made quite chillingly real.

Books have marked some of the most important passages of my life and positioned me in continuous dialogue with strangers whose work influenced my values, mirrored my inner turmoil, provided me with delight and moments of bliss. There are stories we need that often only a book can tell.

I AM huddled, as I often am as an adolescent, in the attic of our house. Seeking isolation. Alone time. I am reading. Oliver Twist, Jane Eyre, Vanity Fair. I am boisterous and shy, moody and misunderstood. But in the attic, none of that matters. Books are a magic carpet I ride to a place outside myself, into worlds seductively strange yet familiar. A classmate at school is as vain as Vanity Fairs Becky Sharpe. I have felt in my bones Jane Eyres self-doubt all too well. I have seen newspaper photos of children as poor as Oliver Twist. I tremble with anticipation each time I open a book. I smile with satisfaction when I read the last page.

1968. I have discovered that Black people live in books and have done things momentous and historic in the world. Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bobby Kennedy are dead, made martyrs by assassins guns. My faith in America has been cremated and cast to the winds. In my grieving I turn to stories that complete the history barely begun in my classes at school. Slave revolts. W.E.B. DuBois, Timbuktu, Nat Turner. Bessie Smith. Ida B. Wells. Books turn me bitter, then they make me proud, and then they make me brave, putting flesh and blood on the bones of a past my Afrocentric father kindled for me in spurts. Books make me a Black Woman.

I AM weeping, too distraught to continue. I cannot imagine actually completing the text. Halfway through Beloved, Toni Morrisons meditation on the price some of us will pay to be free, I am torn asunder. Speechless, I am utterly amazed by the terrible beauty and grandeur of this tale. My tears have been shed in Auschwitz, on the Middle Passage, by rape victims, men dying in trenches, and children lit by the fires of Hiroshima. Yet in the end, the tears leave me replenished, fortified with a courage I have never known. I open the book. I can bear anything.

M Y MARRIAGE has become a prison. I am seriously considering divorce and find myself reading Madame Bovary, Gustave Flauberts ode to illusion, fleeting romance, marriage, and adultery. Because I love life much more than the novels heroine Emma Bovary does, and I have a child to live for, unlike Emma, there will be no suicidal exit from my dilemma. Still, Emma Bovary knows more about me at this moment than anyone else. She alone knows the perimeters of the tomb my life has become. In this, my darkest hour, this fictional character is my best friend.

E ACH OF those books enlarged me. Growing up in Washington, D.C., in a close-knit African-American community, in the waning days of segregation, nineteenth-century British classics were my first international passport. While much of the history of African Americans had been marginalized by mainstream history books, a band of dedicated Black and White historians had, nonetheless, worked to fill in the missing pages of my and my countrys complex, compelling story. Beloved plunged me into the deepest end of the ocean of our inhumanity toward one another and our redemptive impulses that manage, somehow, to ennoble our souls. Reading