Thomas Jefferson, Americas founding father and third president, understood the power of words, not just to inform but also to inspire. In a letter to John Adams, he wrote, I cannot live without books. Nor did Jefferson believe his new country and its citizens could live without a library. Established in 1800, the Library of Congress is the worlds largest library and uniquely American, reflecting this countrys cultural nationalism.

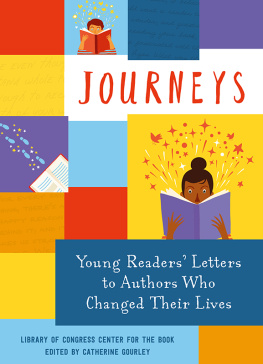

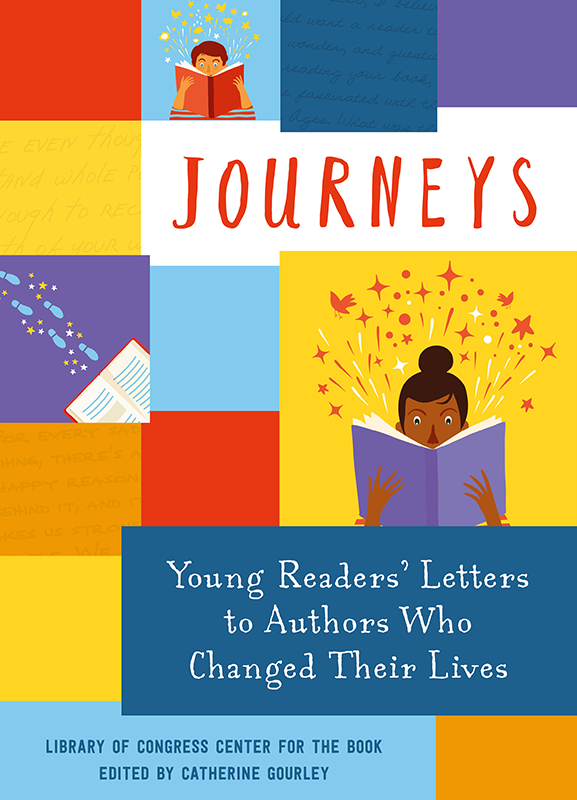

The Center for the Book in the Library of Congress fulfills Thomas Jeffersons philosophy of promoting libraries and the development of lifelong readers through programs that celebrate our countrys literary diversity and leadership. Letters About Literature is one of the Centers most popular reading promotion programs for young people.

The Centers own journey with Letters About Literature began in 1984 with a program called Books Make a Difference, an annual essay-writing contest cosponsored by Weekly Reader. Over time, the program grew into the more personal venue of letter writing something Thomas Jefferson, too, would appreciate. He spent hours each day writing correspondence, what he called his pen and ink work.

Over the years that Letters About Literature has invited young readers to share their personal responses to authors with us at the Center for the Book, we have learned that children often approach reading with reluctance and that writing about what they read is often a challenge and, for some, a struggle.

This volume of letters is a showcase of young minds and hearts inspired and at times healed by the power of an authors words. As the letters so poignantly illustrate, not all books are right for all readers. Likewise, two readers can interpret and respond to the same book quite differently. For some children, finding that right author, that right book, is in itself a bit of a journey. Once a reader finds that author and that book, something remarkable occurs. Readers discover themselves within the pages of the book. They begin to feel and to understand.

Each year, thousands of young readers send us their letters. Their pen and ink work is personal and thoughtful and sincere. Thomas Jefferson would be proud of these young readers not simply because they read books, but because they think about the books they read.

John Y. Cole, Director and Founder

The Center for the Book in the Library of Congress

In a letter to author Veronica Roth, a young reader writes, Books can take you places, places that dont exist but come to life because we all have imagination. You meet the characters, you get inside their heads, know what theyre thinking. And then you get attached to them. They worm their way into your heart and they dont budge. Thats how I know Im reading a great book.

This book is an atlas through some young readers literary journeys, as told in the letters theyve written to authors living or dead, whose works have touched them in very personal ways.

For twenty-five years, the Letters About Literature competition, promoted by the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress, has challenged readers in grades four through twelve to explore how books have changed their view of their world or themselves. Its the Center for the Books most popular national reading program to promote reading among young people.

But why letters? Why do so many twenty-first-century young readers, all of whom are expert at texting and tweeting and social mediating, willingly revert to such an old-fashioned form of communication?

A letter is not abstract or virtual. Like those other forms of communication, it travels through space and time, but oh so much more slowly. That slowness is sweetness. Theres an anticipation for the writer, sending it off, wondering if it has arrived yet. And then theres an anticipation for the recipient, opening the envelope and unfolding the paper. The reader can touch it and perhaps even sense the presence of the writer who formed the words. Letters can be history. Letters, tied in bundles and saved in drawers, have so often been stepping-stones for readers that span decades, even centuries!

A letter is far more private than a status update on a social network. With the private comes the personal, and because letters are so personal, they are insightful. In their letters to authors, the young people represented in this collection tell us what they value and desire as well as what they fear or dread.

Like a drawer of saved letters, this collection is arranged in bundles. Here, the bundles are grouped by upper elementary, middle-school, and high-school letter writers, and, within each of those categories, further grouped by the stages of a journey: destination, realization, and the return home. The title for each passage is a phrase taken from the young readers letter. Each letter is introduced with a short passage about the author and the work about which the reader has written. The letters have been minimally edited so as not to interfere with the writers voice.

Journeys is not about lessons learned. Rather, it is a travel catalog of sometimes exciting, sometimes emotional destinations to which young readers book passage. It illustrates, often poignantly, how reading can take us away from the present and bring us back home again, transformed with new insight into ourselves and our world.

When journeying to Elsewhere, Jonas found bits of joy in the colorful blue sky, a sweet scented flower, or the throaty warble of a new bird. The Giver showed me that even simple things in life are beautiful, such as the rich smell of a chocolate bar or the bright yellow of a leaf in fall.... Its amazing how much a novel that is well written can affect a person. It will not only change the way you think, but if it is good enough, it can change the way you act.

Lucy Dyal in a letter to Lois Lowry about her book The Giver

These times are too progressive. Everything has changed too fast. Railroads and telegraph and kerosene and coal stoves theyre good to have but the trouble is, folks get to depend on em.

So says Pa in Laura Ingalls Wilders The Long Winter, the sixth book of her Little House series, based on her own childhood on the American frontier in the late nineteenth century. Born in 1867 near Pepin, Wisconsin, Laura moved with her family farther westward when she was not quite two years old. Pa and Ma settled for a time in Kansas, then moved once again to Minnesota, and eventually to the Dakota Territory. Laura attended school infrequently. Still, she and her sisters taught themselves, as many pioneering families did during this time. In 1882, Laura received her teaching certificate.