Copyright 2012 by Rick Bass

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bass, Rick, date.

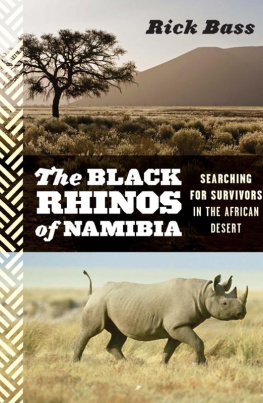

The black rhinos of Namibia : searching for survivors in the African desert / Rick Bass.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-05521-3

1. Black rhinocerosNamibia. 2. Bass, Rick, date.TravelNamibia. 3. NamibiaDescription and travel. 4. Wildlife conservation. I. Title.

QL 737. U 63 B 37 2012

599.66'8dc23

2011051598

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

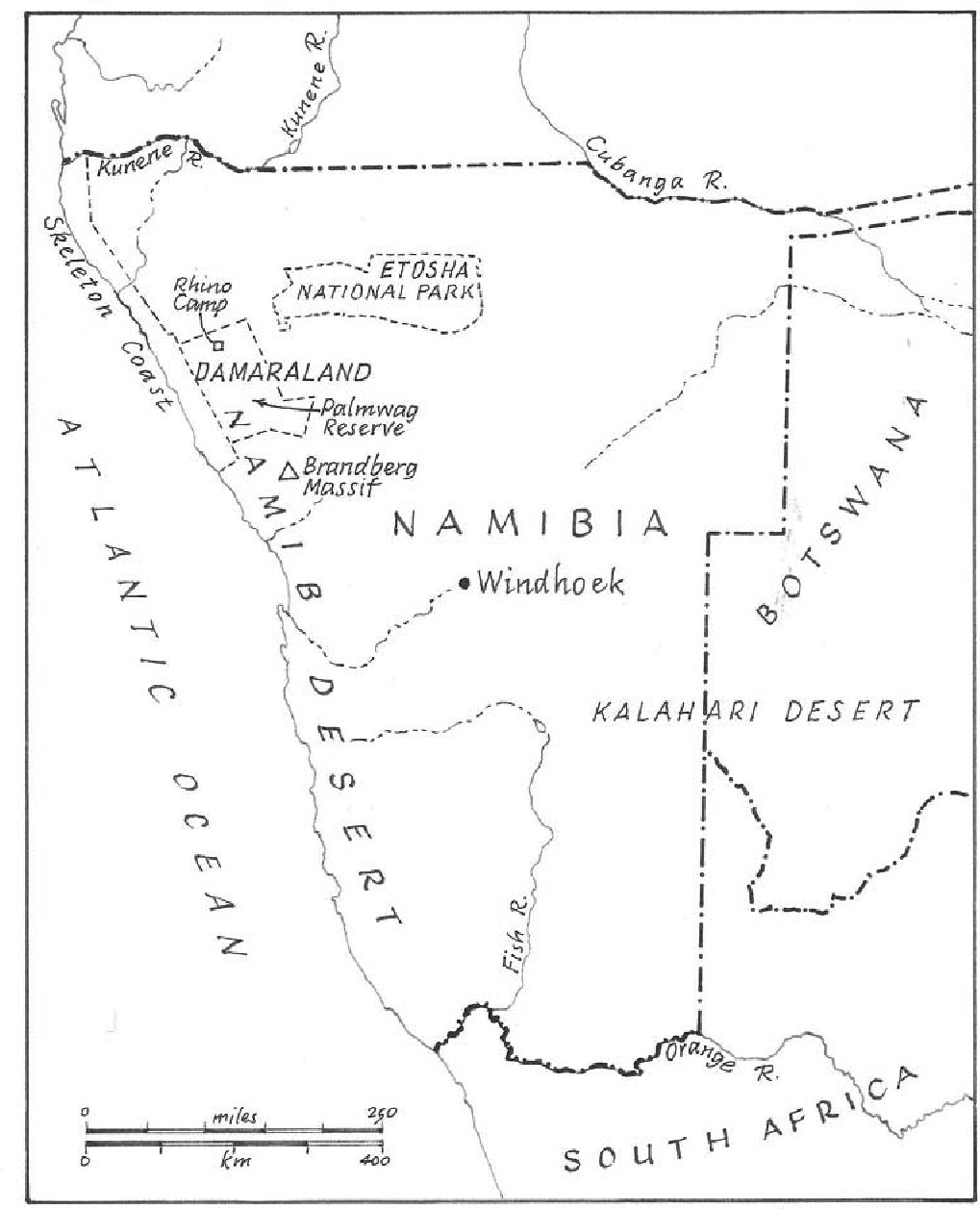

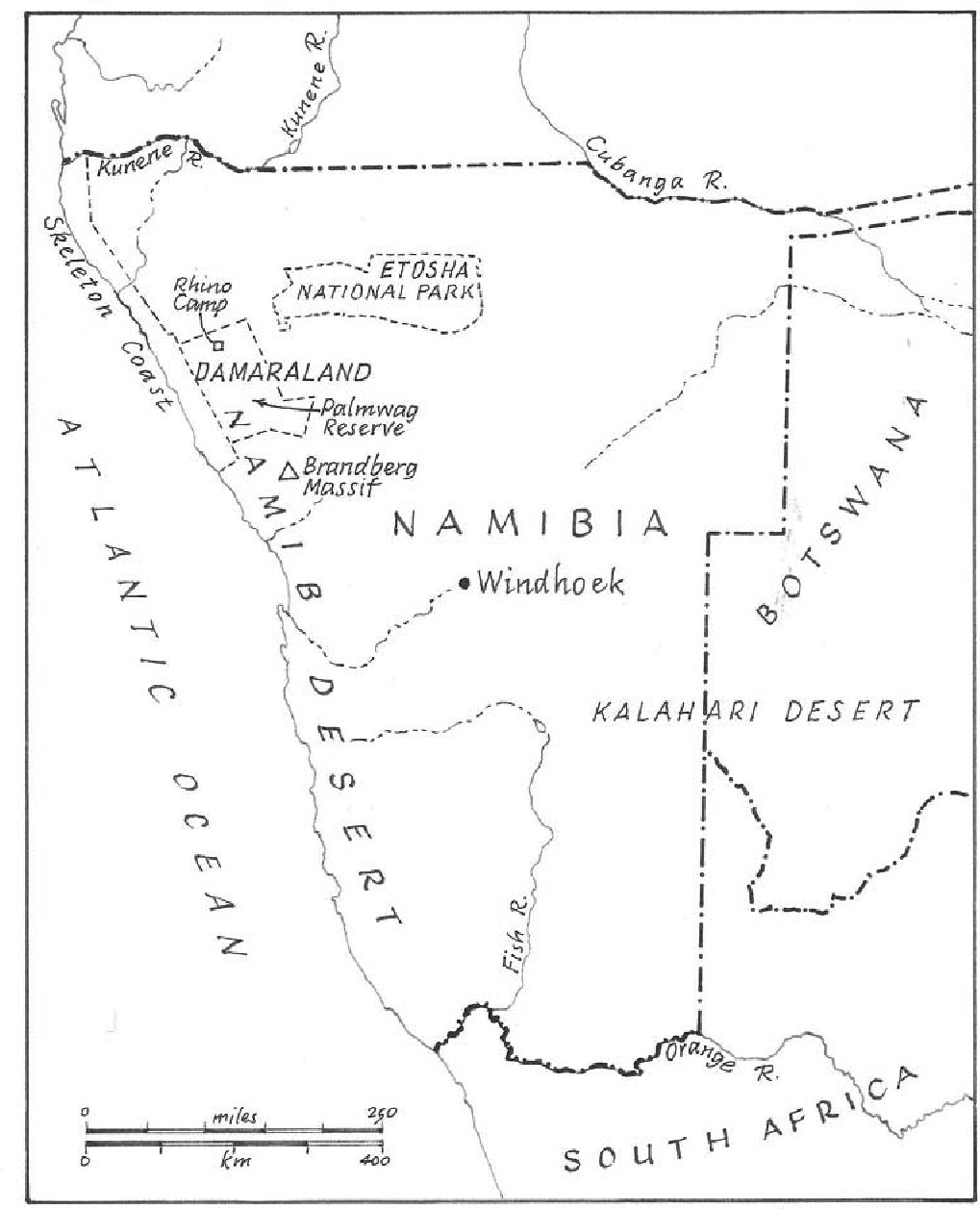

Map by Jacques Chazaud

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Prologue

I had been apprehensive about traveling to Africa, not yet understanding, as I do now, that the world is Africa: that Africa has been at the back of the worlds curve for so long that it is now nearing the front again; that the rest of the world, which came from Africa, is becoming Africa again, as if the secret yearnings of an older, more original world are beginning to stir once more, desiring and now seeking reunification by whatever means possibleperhaps subtly, or perhaps in a grandiose way.

There is less and less a line, invisible or otherwise, between Africa and the world. And rather than arousing alarmor is this my imagination?it seems possible that as Africas long woes and experiences become increasingly familiar to the larger worldradiating, as the origin and then expansion of certain species, including our own, is said to have radiated from Africa, into the larger or farther and newer worldwe are turning to Africa not with quite so much colonial patronizing, but with greater respect, partnership.

There are those elsewhere in the world recognizing now that although Africa cannot by certain measurements be said to have prospered, it has, after all, survivedwhile many in the United States, for instance, exponentially less tested, are already buckling and fragmenting, falling apart at the seams. I am not saying our country yet has a whiff or taste of Africas troublesbut I am suggesting that perhaps our own little sag is creating a space within us for something other than arrogance, and maybe even something other than inattention.

One country in Africa, Namibia, is fixing one problemand I will not label it a small, medium, or large problemwith creativity and resolve. Thats one problem solved, with a near eternity of problems still remaining. But its a start.

We in the United States, on the other hand, are moving backwards: removing nothing from our checklist of either social or environmental woesstill proceeding, with the absurd premise that there is a wall between the twoand, in fact, adding to our lengthy checklist of unsolved problems and crises. Often we create new problems as we go, trudging into the next century with considerable unease, as if not only poorly sighted but possessing none of the other sensors at all, compassion included. Moving forward into the twenty-first century, but backwards into time and history, while some countries in Africa (and elsewhere) inch forward.

What is the individuals duty in a time of warecological and otherwise?

What is the individuals duty in a time of world war?

Always, the two most time-tested answers seem to arise: to bear witness, and to love the world more fully and in the moment, as it becomes increasingly suspect that future such moments will be compromised, or perhaps nonexistent.

And yet: one would be a fool to come away silently from the Namib Desert, having seen what Ive seenpeople in a nearly waterless land continuing to dream and try new solutions that are land- and community-based, and who move forward with pride and vigor and, perhaps rarest and most valuable of all these days, the vitality of hope.

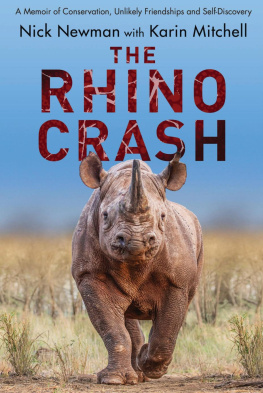

The rhinoguardian of this hard edge of the world, pushed here to the precipiceis giving them hope.

Part I

PASTORAL

H AVING ALWAYS BEEN SOMEWHAT CLUMSY IN THE WORLD , and growing more so as I begin to age, I agreed to travel to Africa with my friend Dennis with some apprehension. Dennis, a burly fellow whose presence in the worldhaving had his arm nearly whacked off at the shoulder by a float plane propeller, and having been charged and knocked down by grizzly bears, enthusiastic rugby players, and othersis still, even after a half century, sometimes extremely exuberant. He tends to see only the positive lights of the worldthe bounty over the next risewhereas I am a practical worrier. And knowing of my clumsiness, I worried that I might make mistakessimple errors in local customs, out in the bushthat would conspire then to be our undoing. I wasnt so concerned for myself, but was keenly aware of my responsibilities as a parent, of the need to stick around for my girls.

And yet: I wanted to see a rhino. And not just any old rhino. The white rhinos of South Africa were at that time prospering, inhabiting the brush and veldt country, gigantic and mythic creatures whose appearance, sudden or otherwise, amid the leafy, thorny scrub, or seen grazing at dawn on the pastoral green of a bedewed meadow, should have pleased the desires of any middle-aged man beginning to wonder at what he might not yet have seen or known in the world.

But a white rhino evidently wasnt good enough. Dennis and the staff and students of his Round River Conservation Studiesa nonprofit group he founded about twenty years agowere participating in a study of black rhinos. They are rarer and more estranged from the world, you could say, inhabiting the edge of the spooky and surreal Namib Desert, caught between the uninhabitable superheated giant sand dunes (some nearly two hundred feet high) that plunge down into the South Atlantic Ocean, and the scrabbling swell of human communities that cluster farther inland.

In this space between humankind and the uninhabitable abyss lived, and live, the last of the black rhinos, and the first of the black rhinosthe recolonizing stock, if the black rhinos are to ever be restored to the world they once strode in almost unimaginable numbers and with what must have once seemed like almost limitless distribution.

There is perhaps no greater animal that has been relegated and confined to so small and finite a space. Surely it would be an amazing sight to any traveler to witness, like a voyeur, the grace, elegance, and dignity with which these last rhinos inhabit the austere country that the world has bequeathed to them.

The Namib Desert is one of the oldest unchanged landscapes on earth. A meandering contour of basalt prairie that rests like the fuzzy light between dream and wakefulness, in this ribbon of land between the oceans dunes and the last of the human communitiesthe out-flung, hardscrabble goat-herding villagesthe rhinos desert, known informally in recent times as Damaraland, is almost identical, meteorologically and geologically, to how it was more than 130 million years ago.

Because it receives between only one and five inches of rain per yearyear in and year out, across the eonsthere is little vegetation that grows there, and, as with much of sub-Saharan Africa, life revolves, like a tiny model of our earth, around the presence of water. It is the nearly eternal absence of water that has shaped and sculpted everything in this part of the worldcrafting each individual species, and then the movements of populations and cultures, and the relationships between these things, with such godlike intricacy and sophistication that it seems surely some foreknowledge must exist: for surely such intricacy of fit and design cannot be random or crafted on the fly, but instead was laid out earlier, as if by some ancient and celestial cartographer.

Next page