Relicts of a Beautiful Sea

This book was published with the assistance of the Wachovia Wells Fargo Fund for Excellence of the University of North Carolina Press.

2014 CHRISTOPHER J. NORMENT

All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America.

Designed by Sally Scruggs and set in Calluna by codeMantra.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Complete cataloging information for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-4696-1866-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-1867-8 (ebook)

18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

Portions of Pattiann Rogerss poem, Animals and People: The Human Heart in Conflict with Itself, have been reprinted by permission of the author from Orion 16(1) (Winter 1997); Pattiann Rogers, Eating Bread and Honey (Milkweed Editions, 1997); and Pattiann Rogers, Song of the World Becoming: New and Collected Poems (Milkweed Editions, 2001).

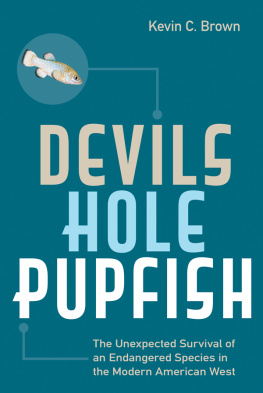

This book is dedicated to those who have worked so hard for so long to protect the voiceless ones, the pupfish, salamanders, toads, and their kintoo many people to name here, but in particular, Phil Pister and Jim Deacon

Contents

Prologue

Oh My Desert

A Cultivation of Slowness

The Inyo Mountains Slender Salamander

(Batrachoseps campi)

Surviving an Onslaught

The Owens Pupfish

(Cyprinodon radiosus)

Some Fish

The Salt Creek and Cottonball Marsh Pupfishes

(Cyprinodon salinus salinus and Cyprinodon salinus milleri)

A Fragile Existence

The Devils Hole Pupfish

(Cyprinodon diabolis)

Swimming from the Ruins

The Ash Meadows and Warm Springs Amargosa Pupfishes

(Cyprinodon nevadensis mionectes and Cyprinodon nevadensis pectoralis)

Exile and Loneliness

The Black Toad

(Bufo exsul)

Epilogue

Hold Steady

Illustrations

Death Valley region

Geological time scale

Inyo Mountains slender salamander

Owens pupfish

Pleistocene lakes and rivers of the Death Valley region

Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

Black toad

Relicts of a Beautiful Sea

Prologue

Oh My Desert

Oh my desert. You have bred the viscid scent of creosote in the searing air, thick spines out of the arid soil, the scuttle of scorpions from the calcined ground, this thermal litany of desiccation and desire: shadscale scrub, Panamint alligator lizard, bursage, tarantula and tarantula hawk, salt-crust playa, Basin and Range, spare hills rising from their own rubble, the long view across the lost miles, a longer view down the corridors of time, a deluge of heat and light. Life takes its path; lineages of reptiles and arachnids, insects and cacti, all at home, drift down the long slope of history, eddy and course through time. The tangled bank yields to naked rock; a ravens guttural croak echoes down some dry wash; a cast snake skin, thick with keratin, lies below a drifting dune; a kangaroo rat, huddled in its burrow, shelters from the solstice sun: in this xeric world these things make absolute sense. But it is more difficult to acceptto believe inthe sweep of fins through a thin film of water, the silent sway of salamanders across moistened soil, a trill of toads in the desert night.

I walk for hours across the hardscrabble ground, beneath a sun-blasted sky, taste salt on my burnt skin. But then I am taken, suddenly, by a trace of seep willow, the rustle of cottonwood leaves, a tiny spring hidden in some rough canyon. I stoop down, cup water in my hands, feel its cool welcome on my face, and then turn a flat rock. A small creature coils, refugee from the deepest past, from another, wetter time. I catch my breath and time spirals. The day is consecrated. All the worlds lost, aching beauty comes flooding in and lifes long skein claims my heart.

Introduction

They are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.

Henry Beston, The Outermost House

Relicts of a Beautiful Sea is a story about the natural world, woven out of science, poetry, aesthetics, and personal experience. It is a tale about the beauty of the Great Basin, its life, and my longing to belong fully to a place and find resonance in its creaturesin other words, to locate myself in this world and so claim a home. And in this age of extinction and collapsing species ranges, my story also is an argument about biodiversitys inherent right to exist. This right was codified by the 1973 federal Endangered Species Act, but many people still wonderwhy should we cherish and protect the many threads of lifes deep and intricate history, and just what are all the lonely and besieged species worth? This story and my argument are built around six desert animals, all of them small and restricted to aquatic habitats: a salamander, four types of pupfishes, and a toad. These animals depend upon the same desert waters that people desire, and so they are rare and mostly threatened. And because they are small and live in a tough and inaccessible part of the world, they also are relatively obscure and carry little of the innate appeal associated with charismatic megavertebrates such as gray wolves, polar bears, California condors, giant pandas, and whooping cranes. And yet in their own right these creatures are as stunning and compelling as wolves and bears, and as worthy of our love and concern. The salamander is one of only two desert salamanders in the world. The pupfishes are considered to be freshwater fish, but some of them can survive in water twice as salty as seawater, at temperatures over 100F. The toad is exiled to an isolated desert valley a world away from its nearest kin. To hold one of these salamanders or toads in your hand, or to watch a small school of pupfish arc through a tiny pool of desert water, is to discover something vital about wonder, and the tenacity of life. And because these animals are rare, and mostly isolated from their nearest kin, they also may teach us something crucial about what it is like to be alone in the world, and how to transcend this loneliness. I know that this has been true for me: living with these rare desert creatures and coming to know their stories has helped heal some of the emotional wounds that I have carried with me out of my childhood.

To fully understand any story you must begin with its settingin this case the spare and aching Great Basin country running east from the Sierra Nevada, a land that rises and falls in an endless iteration of mountains and valleys. A march of desert, 200,000 square miles of it, backlit crenellated hills stretching north and south: a touch of trees in the high places, a drift of luminous clouds across empty territory, of lonely highways through deep and lovely valleys. A threadbare blanket of ragged shrubs draped across the land, the scent of dust and sage in the afternoon air, two or five or ten inches of rain and snow per year. Heat and light in the summer, cold and light in the winter, the waters of the land in pockets and pools, always rationed and rare, running onto salt-pan playas, disappearing into the great empty basins, draining into the gesso ground, alkaline wastes glistening beneath the noonday sun, held beneath the ragged strike and dip of the lost ranges. It wasnt always this way, though. Once there was more water: giant lakes arrayed like fingers splayed in soft sand, tracking the basins. Pinyon pine, juniper, and oak ran across the great valleys; glaciers nestled against the highest peaks; the spoor of mastodon and mammoth littered the ground. It would have been somethingto stand above Death Valley and see a lake 80 miles long and 600 feet deep, cupped between the Panamint and Funeral Mountains. Lake Lahontan, Lake Russell, Searles Lake, Panamint Lake, Lake Manly: gone these last 10,000 years, gone with the giant ground sloths and saber-toothed cats, gone with the glaciers. The gulls that wheeled above the lakes, the fish that swam through the waters, the snails that crawled amid the algae and reedsall the creatures that lived with the waters would have gone elsewhere if they were able, or perished, or followed the dying streams into springs and hidden canyons. And in these places the descendants of these refugees have lived on for generation after generation, wedded to the promise of water flowing from the mountains or rising up out of the ground, a liquid fossil drifting through thick beds of rock and time.

Next page