Contents

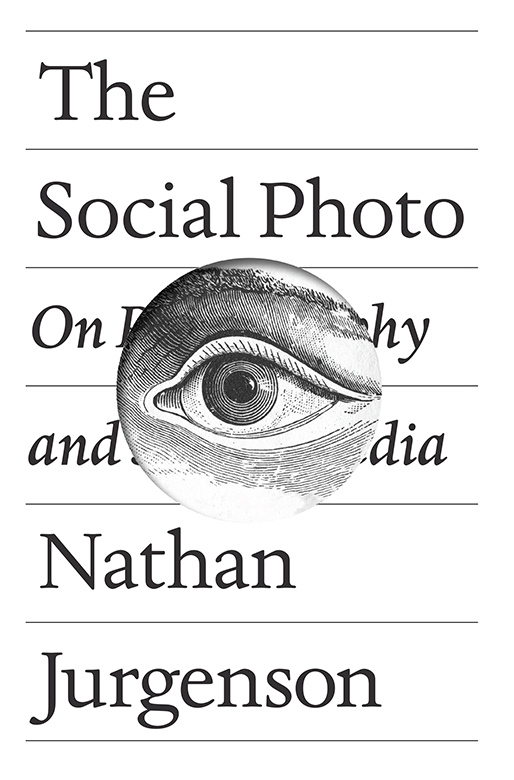

The Social Photo

The Social Photo

On Photography

and Social Media

Nathan Jurgenson

First published by Verso 2019

Nathan Jurgenson 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-091-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-545-7 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-546-4 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jurgenson, Nathan, author.

Title: The social photo : on photography and social media / Nathan Jurgenson.

Description: New York : Verso Books, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018016700| ISBN 9781788730914 | ISBN 9781786635457 (UK EBK) | ISBN 9781786635464 (US EBK)

Subjects: LCSH: PhotographyPhilosophy. | PhotographySocial aspects. | Vernacular photography. | Computer file sharing. | Online social networks.

Classification: LCC TR183 .J87 2019 | DDC 770dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018016700

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Group

For Annette, Cicely, Kim, Tony, and Josephine

Contents

Every day the urge grows stronger to get a hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeness, its reproduction.

Walter Benjamin, 1936

Its the little things: your friend who texts instead of ringing a doorbell. A bus filled with people looking at phones instead of newspapers. And its the bigger things: waves of protesters using these same phones to crowd the streets and overthrow long-established regimes. Even those who do not remember a time before smartphones are born into a world still reeling from the collective vertigo of the dizzying changenot just in the technologies and devices but in interpersonal behavior and political realities. Social norms and understandings try to keep up with the modifications in how we see ourselves, others, and the world as a result of new digital, social technologies. Collectively and individually, in different ways and to varying degrees, we struggle with the personal and social changes that come with redefining visibility, privacy, memory, death, time, space, and everything else social media is currently challenging.

We have conceptual tools to help understand these changes. Operating systems use metaphors like files and folders to make the workings of a computer more comprehensible. Weve developed a spatial understanding of the digital when we say we are going online to a cyberspace; the metaphor makes for good fiction because it frames newness within something familiar. Perhaps less intuitively, the emergence of photography in the mid 1800s can help us understand the contemporary rise of social media.

Photography arrived as a new technology like a kind of magic, allowing you to document the world in new ways and to share these frozen bits of lived experience with people who werent present for them. It changed the possibilities of time and space, privacy and visibility, truth and falsity. The fact of the camera changed how we saw the world and thus changed vision itself. And the advent of photography occasioned many of the same debates and confusions we currently have with social media, amid another sweeping change in the field of vision. How we see, what we can see, what both social visibility and invisibility mean are changing today as rapidly as they did in the early years of photography. Once again, the entire set of ways people make themselves visible to the world, and make the world visible to them, has undergone a substantial reorientation with respect to new devices that capture and share.

The history of photography has much to teach us about understanding social media and thus much of our contemporary social reality. The current claims that the deluge of web content, comments, and social streams is all banal noise without much signal, that the Internet is making us stupid, echoes what poet Charles Baudelaire said in 1859 of photography: If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the multitude which is its natural ally.

To understand social media, we need to understand that vision changes; how we see is historically located and socially situated. We cannot understand photography or social media without stepping back and looking at the deeper impulse that fuels both: the desire for life in its documented form.

Technology and nostalgia have become co-dependent: new technology and advanced marketing stimulate ersatz nostalgiafor the things you never thought you had lostand anticipatory nostalgiafor the present that flees with the speed of a click.

Svetlana Boym, 2007

Snowstorms produce a blizzard of images. The Snow Day is exceptional and thus picture worthy. Each extra inch looks like progress and is thus photographable. Everyday surroundings that usually seem to have exhausted their photographic potential are breathed new productive life. Look how different things are right now. And snow photos look good. The white wash makes the image simpler and more striking by removing extra elements from the frame. The bright snow provides instant contrast, making any subject pop. The flurries in the wind provide movement and texture and depth. The snow itself falls and is blown into beautiful and unpredictable arrangements, wrapping around the contours of objects smooth and lifelike. Even when shot in color, snow photos can appear almost black-and-white. Snow is its own photo filter.

Over New Years 2010, the northeastern United States was blanketed by large snowstorms, and social media streams were covered by photos that captured these white-out urban snowscapes. But beyond the shared impulse to document a dramatic weather event, these images had something else in common: many were similarly faded and grainy, appearing to have been taken on a cheap film camera decades earlier. The sudden influx of retro, faux-vintage images belonged to a new photographic trend, inaugurated by two competing mobile-phone apps: Hipstamatic, named App of the Year in 2010 by Apple, and Instagram, which would eventually emerge as a dominant social photography network. Hipstamatic triggered the popularity of old-fashioned-seeming photos, producing square, fake-aged images modeled after earlier film cameras such as the Polaroid. Instagram came next with a larger set of filters (more flavors of vintage) and a popular network to post them to.

While making an image black-and-white had long been a quick route to making a photograph seem older than the moment it captures, faux-vintage filters offered a wider array of tools for a more flexible approach to nostalgia fabrication. Among other things, filters would fade the image (especially at the edges), adjust the contrast and tint, over-or undersaturate the colors, simulate lens effects and color distortions such as chromatic aberration, blur areas to exaggerate a shallow depth of field, add imitation film grain, and so on. Often, the photos are made to mimic the look of having been printed on physical photo paper.