Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

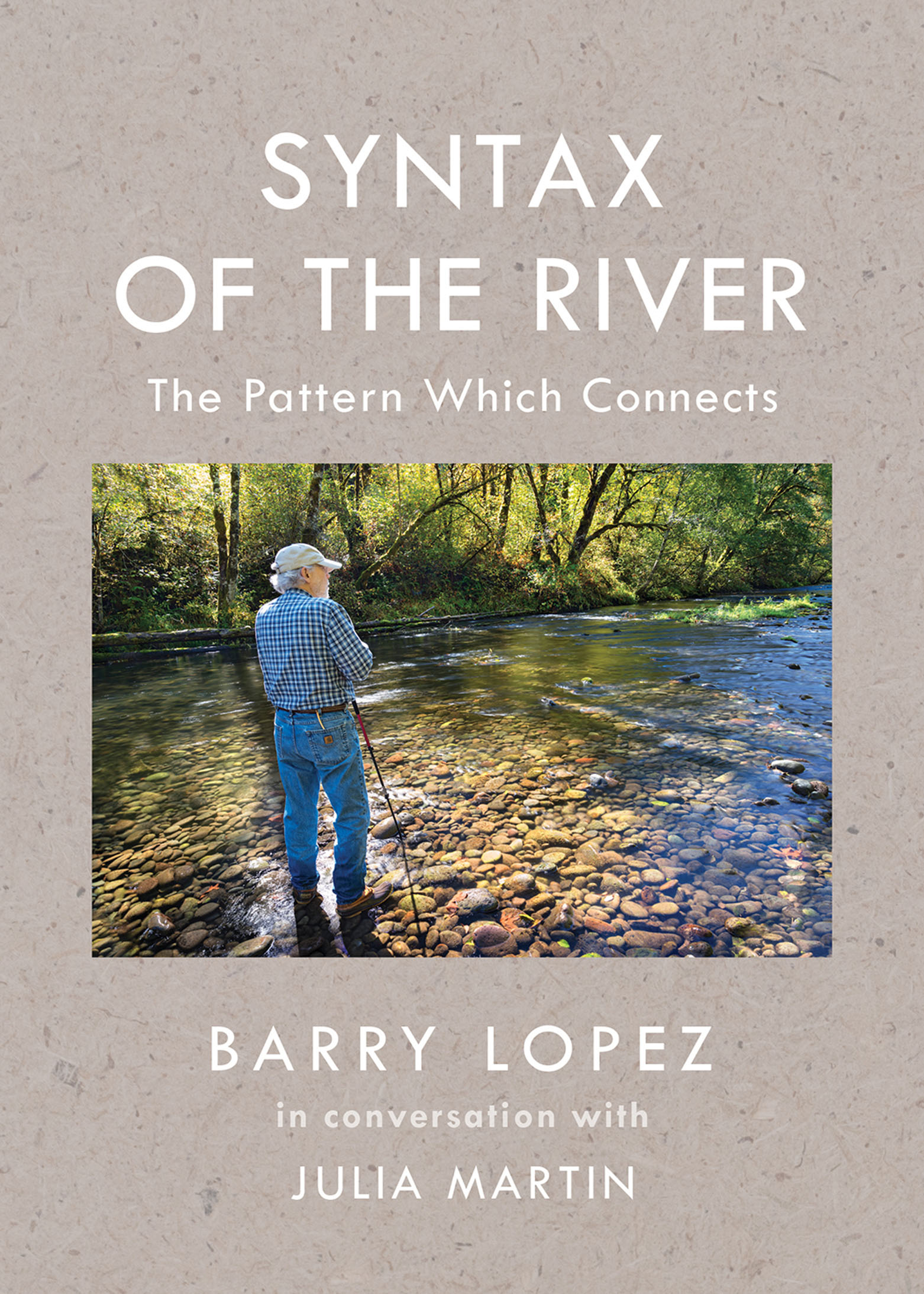

SYNTAX OFTHE RIVER

The Pattern Which Connects

BARRY LOPEZ

in conversation with

JULIA MARTIN

TERRA FIRMA BOOKS /

TRINITY UNIVERSITY PRESS

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

Terra Firma Books, an imprint of

Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2022 by Julia Martin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover design by Rebecca Lown

Book design by Amnet

Cover photo by Tim Giraudier (beautifuloregon.com), used courtesy of McKenzie River Trust

Author photo, Julia Martin and Barry Lopez, 2018, by Debra Gwartney

ISBN 978-1-59534-989-7 paper

ISBN 978-1-59534-990-3 ebook

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all-natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi 39.481992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress

26 25 24 23 22 | 5 4 3 2 1

For Debra and for the McKenzie River

The river is not a thing. [] It is an expression of biological life in dynamic relation to everything around itthe salmon within, the violet-green swallow swooping its surface, alder twigs floating its current, a mountain lion sipping its bank water, the configurations of basalt that break its flow and give it timbre and tone.

Barry Lopez, The Naturalist

CONTENTS

THE SOUND OF WATER

JULIA MARTIN

There was a little black plastic bear on the dashboard of the truck when Barry Lopez fetched me from the airport. I noticed because it was just like the one Id been carrying in my backpack since arriving in the United States. The polar bears elsewhere in the truck, he said, the big mother.

Bears in the old Toyota truck seemed about right. For decades Barry had pondered the conundrum of human peoples relation to other beings, traveling across the world to explore the mystery, and returning to write luminous prose that somehow combined lyrical observation with a great deal of information. His writing spoke directly to work in literature and ecology that Id been doing in South Africa for some years. And after we met through our mutual friend Gary Snyder, Barry became a dear friend too, even a teacher.

So in fall 2010, I visited him at his home in Finn Rock, Oregon. The formal part of the visit involved recording a conversation about his work that extended over three days. For this, we sat at the window of a small wood cabin at the edge of the McKenzie River, with my little black bear on the table beside us. During the rest of the time we drove for hours through deep green forests, slowing the truck to a walk so as to get out and look at Douglas fir cones with the little mouse tails peeping out, a piece of horsetail snapped off and used for cleaning teeth, wild garlic chewed, mushrooms in the damp near a waterfall, a Townsends chipmunk, a chickadee, a marten crossing our path. And we told many stories: stories of bear and elk and mountain lion passing through, stories of home and away, and stories of the interwoven joys and sadnesses of our lives. In all this, Barrys capacity for openness, focus, and seriousness were unrelenting. It was an intense time, and I felt at once exhausted and elevated, the recipient of something irreplaceable. Three words in my journal noted what seemed like the heart of it: respect, kindness, suffering.

On returning to Cape Town, I had the recording transcribed. The typist noted that the sound of water was continuous in the background throughout the interview and said working on it had been a gift of peace at the end of the year. This was good to hear, and I sent the text to Barry to edit, hoping to publish it soon. But there it sat. He kept meaning to work on the conversation, but it was really long, and rather more rambling in structure than hed have preferred. And of course other things kept intervening. His massive book project, Horizon, which was finally completed in 2018, took up most of his writing energy. Then there was a serious cancer diagnosis, and the years of diminishing strength and determined courage that followed. Curiously, the deferred publication of the interview became a background thread to our contact over the years, a conversation in itself. Barry would feel remorseful that he hadnt done it, and I would remind him that the main thing was the opportunity the visit had given us to be together.

Two years now since his death on Christmas Day of 2020, the deep blue agapanthus I planted for him are flowering again, and it feels at last time to share our conversation. His wife, Debra Gwartney, whom I met on a later visit and who became a dear friend, is keen for others to read it. And I think Barry would have been too. His words from a letter in 2015 are a poignant nudge to complete the project. Ive no intention of letting that interview slide, he wrote. We worked hard on it and Im determined to do my part with it. It is a beautiful record of our time together, yes, but there is something else there more than worthy of our continued attention. The ball is in my court and one day I will surprise you by returning your serve.

CONVERSATIONS

DAY 1

PATTERN

The quality of Barrys attention was extraordinary. He had the capacity to speak thoughtfully and at great length without a pause, his gaze held in earnest focus. And he could just as well remain quite still and silent for long spaces: listening, seeing, touching, breathing. In all this, he lived anchored in the being of one particular place. For all the journeys of intrepid exploration and adventure across the planet that we know from his writing, it was to this place that he always returned: the thirty-eight acres of deep forest and the reach of the McKenzie River below the house where he lived for fifty years. This negotiation between silence and speech, seclusion and engagement, made for a very fine and highly informed capacity for awareness as well as a powerful desire to communicate it. For while his inclinations were profoundly contemplative, there was also a strong sense of urgency to speak, to share the vision, to write, to help.

On the first day of our conversation, he begins by contemplating awareness itself. Reflecting on a lifetime of watching the river, he describes something of the quality of attention he has learned from intimacy with the place itself: a finely tuned sense of the distinction between silence and stillness, of the rich complexities of the present moment, of the syntax of myriad things in their lively interrelationships. In all theres a perception of the river as a living animal and of the pattern which connects. The stream of thought then meanders from stories about the miracle of Chinook salmon who return on the same day each year to the same place in the river, into the terrifying craziness of a human society focused on me and mine, the suicidal impact of the profit motive, and on to the wonders of the Prado, the Louvre, a glorious symphony.