Thoughtful Images

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197650547

eISBN 9780197650561

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197650547.001.0001

In memory of

my grandmother,

Rosa Oleynick Schiller,

who took me to see

The Responsive Eye

many years ago

Contents

Figures

Plates (located between pages 150 and 151)

The question lying at the heart of Thoughtful Images is this: Can the visual artspainting, drawing, etching, sculpture, etc.produce works that function as illustrations of philosophical texts? Since this book presents an affirmative answer to this question, a second issue emerges: What is involved in illustrating a given philosophical idea or theory? More specifically, can a visual artwork actually make an innovative contribution to philosophy? Spoiler Alert: The book also proposes an affirmative answer to this second question, for I see the arts as, among other things, a way to reflect upon philosophical questions or, to use Robert Pippins pregnant phrase, philosophy done by other means ().

Since few philosophers have written about illustration, I want to explain the circuitous path that led me to write this book. I first became interested in illustration as the result of my participation in the debate concerning whether films can make substantive contributions to philosophy. In reflecting upon that issue, I was struck by the fact that both the advocates for and the critics of the idea of cinematic philosophy claimed that a film that illustrated a philosophical theory or claim was not relevant to the debate, since merely illustrating a philosophical position was not the same thing as actually doing creative philosophy. In Thinking on Screen: Film as Philosophy (Marxs theory of alienation seems to have struck a chord with many readers by demonstrating how a comedy could make a serious philosophical point.

As a result of his reading that chapter as well as subsequently talking with me about our shared interest in comics, Aaron Meskin asked me to write a chapter on visual images in comics for the anthology he was editing. The chapter that I wrote compared the images that grace the pages of illustrated books with those in comics. I wound up making the somewhat paradoxical sounding claim that comics do not standardly contain illustrations, a claim that I will explain and defend in the ninth chapter of this book.

Writing that essay fueled my interest in the topic of illustration itself. As I began to research the issue, I discovered that there was very little philosophical literature devoted to the topic. As a result, I decided to teach a seminar on the philosophy of illustration and was pleased that Mount Holyoke College agreed to hire Barry Moser, the well-known book illustrator, to co-teach with me. In preparing the course, I felt it incumbent on me to see whether there were original works of philosophy that included illustrations by established artists. Initially, I was able to find only one such book, Ludwig ; it was published in a beautiful edition by Arion Press that included Mel Bochners illustrations of the text.

Although Bochners illustrations were quite abstract and difficult to understand, after extended study I came to see them as providing illustrations of some of the central ideas Wittgenstein advanced in On Certainty. I wound up writing an essay on some of the images in the book ( of this book.

While preparing to teach the course and then writing the catalogue essay for the exhibition, I discovered other works of art that that illustrated philosophy in different ways.

Next, Nol Carroll and Jonathan Gilmore asked me to write a chapter about art as philosophy for their anthology on the philosophy of painting and sculpture (). While writing that chapter, I realized that there was sufficient material to justify writing a book about art that illustrates philosophy. The one you are either holding in your hands or looking at on your devices screen is the result of that realization.

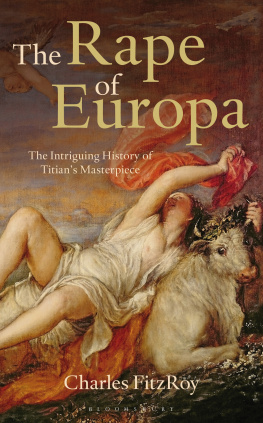

Although my initial idea had been to write a book on the philosophy of (book) illustration, I came to see that the real issue that interested me was the various different ways in which visual artists had engaged with philosophy from the time of the Ancient Greeks to the present. Thoughtful Images is my attempt to document and analyze the rich tradition of interaction between visual artists and philosophy (and philosophers!) that deserves more attention than it has received.

There is one terminological issue that I need to raise. This book includes both written text and images. This makes it problematic to refer to the readers of this book, for they are as much viewers as they are readers. I attempt to solve the problem of how to refer to the books audience members by using a number of different terms. Sometimes, I say reader-viewers to emphasize the dual nature of the text; other times, I talk of the books audience to avoid prioritizing either the text or the images. I do occasionally refer to viewers or readers when I am thinking primarily of a visual or a written text. But throughout, the audience for this book will be simultaneously viewers of its images and readers of its text who integrate both of those roles.

A brief caveat is also in order. The subtitle of this study, Illustrating Philosophy Through Art, suggests that it will be a comprehensive examination of how philosophy has been transformed into art. This is misleading in that both the works of art and the philosophical theories that will be considered belong exclusively to the Western tradition. There are, of course, traditions of philosophy other than the Western one, including those found in China, India, and Africa. I have not included illustrations of philosophy in such traditions primarily because of my own ignorance. I do not know enough about those traditionseither philosophical or artisticfor it to make sense for me to have attempted to include them in this study. I can only hope that others more conversant with those traditions will be inspired by this book to investigate how those philosophical traditions have been illustrated.

I want to thank a number of people without whom this study would never have been written. First, thanks to my friend and co-teacher, the esteemed book illustrator Barry Moser, for many hours of fascinating discussions about the nature of art, as well as for introducing me to a range of illustrations I hadnt known about. Mel Bochner was extremely generous with his time and helped me as I tried to unpack the significance of his own illustrations of philosophy. Andrew Witkin of the Krakow-Witkin Gallery provided me with assistance at an early stage in this project and has continued to be very supportive of my efforts. The entire staff of the Mount Holyoke College Museum of Art assisted me along the way. Although John R. Stromberg, then the director of the museum, came to fear my increasingly demanding requests for his help with my projectwhat began with my simply asking whether the Museum could buy the Arion edition of