The History Of Scotland Volume 8

From The Scots Invasion To The Reformation

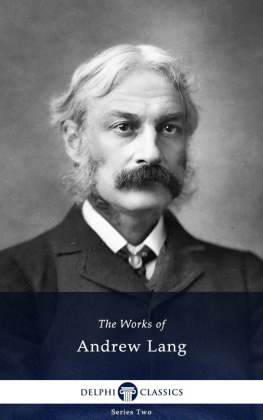

Andrew Lang

Contents:

The Scots Invasion Of England

The Year Of Montrose

THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND VOLUME 8, Andrew Lang

Jazzybee Verlag Jrgen Beck

86450 Altenmnster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN: 9783849604684

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

THE SCOTS INVASION OF ENGLAND

THE presence of a Scottish army at Newcastle, confiscating the patrimony of St Cuthbert and the goods of Catholics or of Anglicans at will, would once have united England in arms. The Scots would have been driven from Tees and Tyne to the Naver, calling on their mountains to cover them. An England united and prepared would have done it: in a few years an England prepared, though not united, did it. But England was now neither united nor prepared. Strafford met the retreating levies of the king at Darlington. Terrified as they were, they were scarcely more uneasy than the Scots had been after their victory at the ford of Tyne. Some 4000 of the Scots army are said to have decamped, homesick no doubt, towards Berwick. Though the numbers are probably exaggerated, Leslie reports (September 2) "the evil carriage of our own soldiers," and " the multitude of runaways, who abandon the army." Says Baillie, who was present, "If Newcastle had but closed their ports, we had been in great hazard of present disbanding," but the garrison was at once withdrawn.

Only the gentlemen of England had fought well. Wilmot had cut down one or two opponents in a cavalry charge: Strafford, from Darlington, reported to Charles, at York, that Wilmot had slain Montrose, a rumour contradicted by Vane on September 3. The counties of Durham and York had begun to show some spirit; even now, had Charles concentrated at York and advanced, the heart of England might have been aroused, whether by victory or defeat. It was not to be. England, apart from all other distractions, was in one of her fits of fear about Popery: as absurd as if Spain had been in terror of a Protestant plot. It was commonly said that whoever was not Scotch was Popish. In place of aiding the king, the chief Puritan peers were in London, agitating and petitioning. They and the middle classes stood towards the invading Scots, as Brunston and Ormistoun, Knox and Glencairn, and the Douglases, had stood of old towards the invading English. They called for a Parliament, for the trial of the king's ministers: while the Scots also now insisted on the punishment of "incendiaries," chiefly Traquair and Hamilton, Strafford and Laud. Baillie, by his pamphlets, was a chief agent in hounding Laud to the block; " We pant," says this clergyman, " for the trials of Laud and Strafford."

We need not dwell on the tragedy of Charles, the familiar steps to ruin with dishonour. The petition of the city for a Parliament was added to the petition of the peers. Hamilton was in terror: he wished to fly the country; that being forbidden he helped the Commissioners whom the Scots presently sent to London, with all his might. He "was very active for his own preservation." The Royalist garrisons in the castles of Edinburgh and Dumbarton yielded to scurvy and starvation. The great Council of Peers met, for the first time since Henry VII., at York. They appointed Commissioners to capitulate to the Scots at Ripon (October 2). In the Scottish camp there was trouble. Montrose, " whose pride was long ago intolerable, and meaning very doubtsome, was found to have intercourse of letters with the king, for which he was accused publicly by the General in face of the Committee," says Baillie. Montrose is said to have been betrayed by Hamilton and the gentlemen pickpockets of the king's bedchamber. Burnet says that his letter to the king happened to fall to the ground, and the address was noticed by Sir James Mercer, who picked it up. Wishart, Montrose's chaplain, blames the gentlemen of the king's bedchamber, who acted as spies for the Covenanters. Of these men, Will Murray, of old the king's "whipping-boy," is the most notorious. He is freely accused of being employed, now by Hamilton, now by Argyll; he is mixed up in every intrigue: he was always suspected, never discarded, and could probably have explained many a problem that history cannot unravel. Montrose's letter was a mere protestation of loyalty, such as the Covenanters indulged in publicly. The king was not " the enemy," so Montrose was safe: he had not communicated with " the enemy." Meanwhile, in the meeting of Scots and English at Ripon, the forgery of Savile was detected. He justified himself by patriotic motives; he too was safe; who could denounce him, to whom? The Ripon meeting haggled over the question of how much the Scots would take to remain quietly where they were. In the end they received a considerable sum of money, " brotherly assistance." The inevitable Parliament, the Long Parliament, met on November 3. Baillie, travelling south with the Scottish Commissioners, reports that the inns were " like palaces." The king at this time reprieved a Jesuit, sentenced to death for being one; the anti-Popish agitation went on; the presence of Rossetti, a papal agent, and the queen's futile dealings with him were resented. The utter uprooting of Episcopacy was clamoured for by the preacher Henderson, in a pamphlet which gave great offence to the English: " diverse of our true friends did think us too rash, and, though they loved not the bishops, yet for the honour of their nation, they would keep them up rather than we strangers should pull them down," says Baillie. The Scots cherished the ambition to see all England Presbyterian on their own model, a lovely dream, that came through the Ivory Gate. The Root and Branch party, however, was powerful and very noisy. But Cheshire petitioners on the Episcopal side objected to " the mere arbitrary government of a numerous Presbytery, who, together with their ruling elders, will arise to near forty thousand Church governors." The Cheshire petition was signed by four peers, more than eighty knights and esquires, seventy clergymen, three hundred gentlemen, and over six thousand freeholders and others. The anti-prelatists produced a counter-petition, in which the numbers all round were exactly doubled! The thing was a forgery, or a Presbyterian joke.

In March 1643 the satisfaction of the Scottish demands for money was postponed to the business of illegally condemning Strafford: " pleasure first, business afterwards." The Scots acquiesced in this arrangement. We do not dwell on a tragedy " too deep for tears," not the death of a brave man already near his end, but the moral overthrow and the worm that never dies in the breast of Charles. He appears to have yielded in fear of mob violence, which threatened the life of the queen. In August the arrangement with the Scots was completed, and, much to the wrath of the English Parliament, the king hurried northwards, to forget, if he could, in changed scenes: to save his servant, the incendiary Traquair, if he could; to procure evidence of English treason in inviting a Scottish invasion; to see whether the name of Stuart might yet have a charm, and make Scotland a rallying -point of resistance against the English; possibly to punish Argyll, who lay, as we shall see, under some suspicion of flat undeniable personal treason. Above all, Charles may have hoped to establish the less enthusiastic Covenanters in the chief offices of State.

Already, in England, Catholics were dying for their religion. William Ward, a priest, was hanged at Tyburn, just as a friend of his, for no other crime than his creed, had perished thirteen years earlier. Resisting the fury of the House of Commons, and the pressure of the mob, as he should have done when Strafford was condemned, Charles now rode out of Palace Yard with his face to the north. The man should repent it, he said, who touched his horse's reins. If we may believe the Venetian Ambassador, the Scottish Commissioners had made him loyal promises. He was their native king: Scotland had ever been jealous of his prolonged absences. But if he expected to win Scotland, to awaken Scottish national sentiment, the king was notably deceived. He went to abase himself in the dust, to assent to all that his soul loathed. He had apparently bought Rothes, by money and place, but at this moment Rothes died. " From him his Majesty expected much service at the present conjuncture, he having given many assurances thereof." He was to have enjoyed high office, in England, and to have married the rich Countess of Devon. We have, perhaps, no right to say that Rothes, the chief fomenter of the Covenant, was bought. He may have been pricked in heart and conscience by the situation of the king. However, there were promises and hopes held before him: to Montrose no bribes were offered. To regard his change of party as the result of personal jealousy and self-seeking, is the note of a mind incapable of understanding a noble motive.