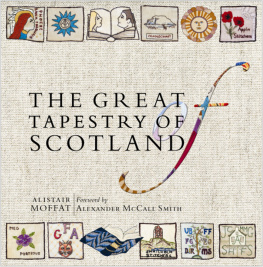

The Great Tapestry of Scotland

Panel 1 stitched by:

KA Two

Linda McClarkin

Carol Whiteford

Stitched in:

Beith, Kilwinning

For all those who have worked on The Great Tapestry of Scotland

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Completed panels from The Great Tapestry of Scotland

copyright Great Scottish Tapestry Charitable Trust

Photographs copyright Alex Hewitt

Panel designs copyright Andrew Crummy

Foreword Alexander McCall Smith

Introduction and other text Alistair Moffat

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-78027-160-6

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-656-4

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Foreword

The tapestry illustrated in this book tells the story of Scotland. As one might imagine, to illustrate the history of a country, even with some 165 panels at ones disposal, is no easy task. Nor is it easy to tell it in a way that brings centuries of a nations existence to life in an entertaining and vivid way. The Great Tapestry of Scotland does all this, and it does it in a way that was instantly recognised and appreciated by the public when it first went on show in the Scottish Parliament in the late summer of 2013. People came in their thousands so many, in fact, that at times the building was thought to have reached capacity and faced the hitherto unthought-of possibility of being closed for a few hours.

I was part of the group of people behind the tapestry project, and I went to the opening with my heart in my mouth. What would the public judgement be on a project that had such large ambitions? Would people find fault with our selection of subjects? Would the artists style fail to resonate with the people of Scotland? I need not have worried for a moment on any of these scores. People stood before the tapestry with wonderment and delight on their faces. Some cried with emotion the greatest tribute, I think, that any work of art can be given. I saw young children gazing at the panels with rapt attention. I saw elderly people recognise images and references and share them with each other with all the joy that goes with discovering something one has long known about but perhaps forgotten or not thought about for a long time. Everybody standing before the tapestry seemed transported by the experience.

The tapestry is the work of more than a thousand people from all over Scotland and beyond. The central artistic vision, though, is that of three people: Alistair Moffat, who selected the subject matter and wrote the text; Andrew Crummy, who drew the designs; and Dorie Wilkie, who supervised and inspired the stitching. All three made this object, but Andrew is the one who must be particularly celebrated as the artist. A man of great modesty, he never seeks praise, but it must be said here that he has, quite simply, wrought a masterpiece.

Then there are the many stitchers who have themselves put their own artistic stamp on the tapestry. Although Andrew designed the main images, he generously left a great deal of scope for individual stitchers to make their own contribution. And they have done so magnificently, adding numerous touches throughout, giving yet more life and colour to this lovely object.

When we started this project, which began with a telephone call I made to Andrew Crummy proposing that we do it, I had no idea that the result would be so lovely and so affecting. I had no idea, too, that in bringing the tapestry to completion so many people would be brought together in friendship. But that has all happened, and now the Scottish nation has something that it can treasure for many years centuries, we hope to remind us all of who we are and all the love, suffering, hope, disappointment, and triumph that makes up the life of a people. I hope, too, that we shall be able to share that with others from other nations, who will see the universal human story written on these panels of linen and perhaps reflect on the ideals of brother- and sisterhood that have always been so important in Scotland and remain so today.

Alexander McCall Smith

Introduction

On a summer afternoon in the 1890s, Donald MacIver drove his pony and trap up the track on the west side of Loch Roag on the Atlantic shore of the Isle of Lewis. A teacher at the school at Breascleit, he found himself completing the last stage of a long journey back into the past. Beside Donald sat an old man. His uncle, Domnhall Ban Crosd, had sailed across the ocean from Canada so that, before he died, he could at last return home. As Donald flicked the reins and the pony trotted up the rise at Miabhig, the vast panorama of the mighty Atlantic opened before them. Below spread the pale yellow sands of Uig at low tide and around the bay lay a scatter of townships.

His by-names hint at Domnhall Bans demeanour. Common enough when used to distinguish the owner of a frequently found name, ban means fair headed but crosd is unusual probably deriving from an English adjective, it is somewhere between obstinate and ill natured. Perhaps the old man set a characteristic stone-face when he gazed on the heartbreakingly beautiful bay at Uig, the water glinting in the summer sun, a sparkle, a sight he had not beheld for fifty years, not since the white-sailed ships slipped over the horizon bound for a new life in Canada.

As Donald guided his pony gently over the rutted tracks, grass growing green on their crests, they came at last to journeys end, the place Domnhall Ban Crosd had seen only in his dreams. It was the township of Carnais, his birthplace, where crofting families had been cleared off the land by the agents of an absent and uncaring aristocracy in 1851. Like many, Domnhall Ban and his people had found good and even prosperous lives in Canada but, in their hearts, there was ionndrainn. It means something that is missing, an emptiness, and, before he grew too old for a long sea voyage, the child of Carnais wanted to see his home place once more. But, when Donald pulled on the reins and braked the trap, there was nothing. Nothing at all to see. The croft houses had been tumbled down, the fences and fields opened to sheep pasture. What had been a busy, living landscape, home to the chatter of children and the day-in, day-out labour of farming families, had simply been obliterated. As he looked around at the desolation, the old mans face at last crumpled and he wept, tears falling for all that experience in one place, all lost and gone, memories that would die with him. Chaneil nith an seo mar a bha e, ach an ataireachd na mara, he said to his nephew There is nothing here now as it was, except for the surge of the sea.

Much moved by his uncles sadness, Donald MacIver wrote his great lyric, An Ataireachd Ard. In memory of loss and change, of the wash of history over Scotland, it begins:

An ataireachd bhuan

Cluinn fuaim na hataireachd ard

Next page