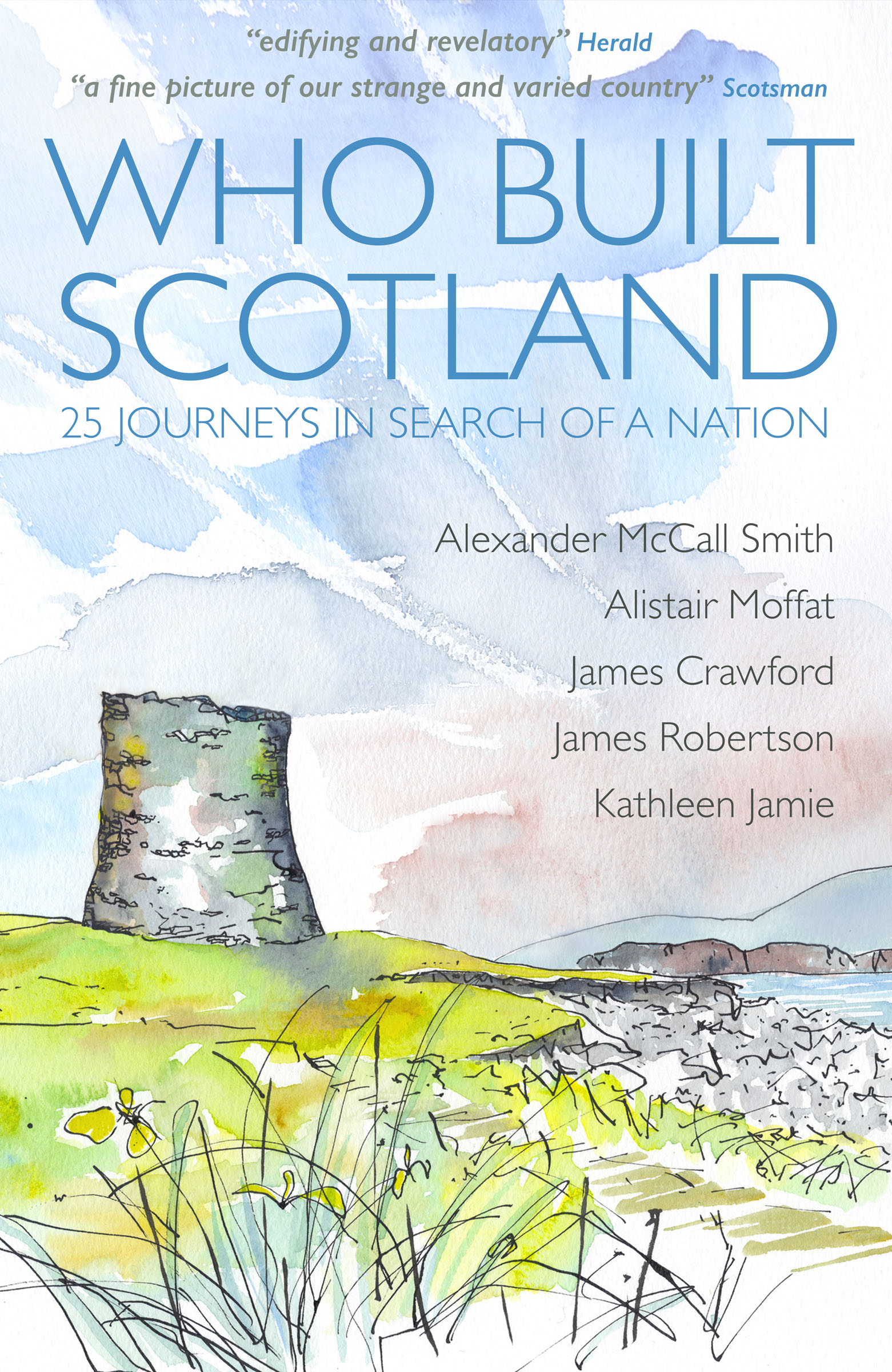

Who Built Scotland

Alexander McCall Smith

Alistair Moffat

James Crawford

James Robertson

Kathleen Jamie

Published in 2017 by Historic Environment Scotland Enterprises Limited SC510997

Historic Environment Scotland

Longmore House

Salisbury Place

Edinburgh EH9 1SH

Registered Charity SC045925

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84917 245 5

Individual chapters remain the copyright of their respective authors:

Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Crawford, James Robertson and Kathleen Jamie

Historic Environment Scotland 2017 Unless otherwise stated all image copyright is managed by Historic Environment Scotland

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of Historic Environment Scotland. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution.

Cover painting by Oliver Brookes

Proofread by Mairi Sutherland

Supported by Creative Scotland

Contents

Kathleen Jamie

Geldie Burn, 800 BC

Alistair Moffat

Cairnpapple Hill, West Lothian, 3500 BC

James Robertson

Calanais, Isle of Lewis, 3000 BC

Kathleen Jamie

Mousa Broch, 100 BC

Alexander McCall Smith

Iona Abbey, AD 563

Kathleen Jamie

Glasgow Cathedral, AD 600s

Alistair Moffat

Edinburgh Castle, 1100s

James Crawford

The Great Hall, Stirling Castle, 1503

James Robertson

Innerpeffray Library, 1600s

James Crawford

Mavisbank House, 1723

James Robertson

Auld Alloway Kirk, 1791

Alexander McCall Smith

Charlotte Square, Edinburgh, 17911820

Alistair Moffat

Glenlivet Distillery, 1800s

Alexander McCall Smith

Bell Rock Lighthouse, 1807

James Robertson

Abbotsford, 1811

Alexander McCall Smith

Surgeons Hall, 1830s

James Robertson

The Forth Bridge, 1881

Alistair Moffat

Glasgow School of Art, 18961909

James Crawford

Hampden Park, Glasgow, 1903

Alexander McCall Smith

The Italian Chapel, 1940s

Alistair Moffat

Inchmyre Prefabs, Kelso, 1948

Kathleen Jamie

Anniesland Court, 1968

James Crawford

Sullom Voe, Shetland, 1974

Kathleen Jamie

Maggies Centre, Fife 2006

James Crawford

Sweeneys Bothy, Eigg 2014

Introduction

Look around you, wherever you are right now. Maybe you are reading this while browsing in a bookshop in a city; or you are on a bus or train rumbling through a town centre; or you are in an armchair in a tenement flat or a semi-detached house or a cottage out on its own, surrounded by nothing but fields and stone dykes. Stop for a moment, and take in all the things you can see. There may be roads and pavements, long lines of concrete and tarmac filled with cars and pedestrians. There may be streetlights, shining down on row after row of houses, stretching off into a suburban distance. Perhaps you are in a hotel, ten storeys high, with a view that takes in a whole city, other buildings far below, thinning out towards hills and a river that widens to the sea. Maybe you are in a village on the coast an old village with a hook of stone harbour and, beyond, out on a promontory, a tall, whitewashed tower with a spinning light, standing alone. Or you are high in the mountains, far away from any urban hum, in a basic, tin-roofed stone bothy for climbers and walkers, reading by the light of a fire youve lit yourself among the ashes of a soot-blackened hearth.

Now think someone, at some time, built all of this. A process was started, long ago, to put things into, and on top of, the land. Permanent things. Things that might, and in many cases have, lasted far beyond the lives of their makers. In simplest terms, at some point, we stopped being just travellers, and we became builders. The fires we made to keep us warm no longer moved from place to place. We put walls around them and roofs over them. We made homes. Places for families places to eat, work, sleep, love, fight and argue. Places to live.

You can still see some of these places today. Travel to Orkney then catch a ferry or if youre brave, a ten-seater twin-prop plane to the northernmost island, Papa Westray, and then head on to a place on the west coast called the Knap of Howar. There, fringed with grass and wildflowers and directly overlooking the sea, are two holes in the ground. From above, seen side-by-side, they look like two footprints: two footprints that were hidden beneath the earth until a storm in the 1930s tore at the sand and soil and exposed the tops of walls made of interlocking stone. Now you can climb down to the shore side, stoop low to pass through a doorway. It is a journey of just a few metres, but also of 5,000 years. You are inside the oldest building still standing in northern Europe. You are sheltered from the wind, but it still whips the air above you, in the empty space that once held a roof. The entry doorway frames perfectly the shore, sea and sky. The sun sets on that horizon. There is a fireplace and the remains of ancient furniture and cupboards. And as you stand there, you realise that it is not so much distance that you feel from the people who built these homes who lived in them for generation after generation as intimacy. Our modern living rooms and kitchens, with sofas and smart TVs and electric ovens and microwaves, arent really so different. You can pull on the thread between now and then and feel it taut and strong.

What we build always reveals things that are deeply and innately human. Because all buildings are stories, one way or another. They each offer their own threads to pull, threads that lead you to ideas, emotions, hopes, dreams, fears and conceits. So go on, look at everything around you and think, really think , about how it got there. Who planned it, who designed it, who paid for it, who actually got their hands dirty making it? Who lived in it, or worked in it, or worshipped in it, or learnt in it, or was born in it, or died in it? Its a dizzying prospect, vertigo-inducing even, when you attempt to peer over the metaphorical parapet at the layers of history upon which all of our lives are built.

In this book, we have picked just twenty-five buildings to take us from a beginning to an (open) end. As a result, we will, inevitably, have missed both the obvious and the obscure. But it is the nature of the journey that is important. Starting with the earliest hearths left behind by our nameless ancestors, we will move steadily forward, and in the process tell a new history of Scotland, rooted in the roots themselves, the things that we have raised up in stone, wood, steel, glass and concrete and that still persist in the landscape, whether hunkered down with unshakable tenacity, or reduced to the faintest of traces. Our five authors have been all across the county in the process, from city centres to remote glens and lonely island peninsulas. They have travelled to these buildings and where they have been able walked inside them or through them or on top of them, to reflect on both their histories and how they relate to personal stories and experiences. This book, then, is an account of twenty-five individual journeys, which come together to form a narrative of a nation. But it is also an invitation to you, the reader, to get out and explore Scotland, to look anew at everything that you see, to reach out to the stones and feel them coarse or smooth to the touch and to find the seam that leads you onwards, on your own journey.