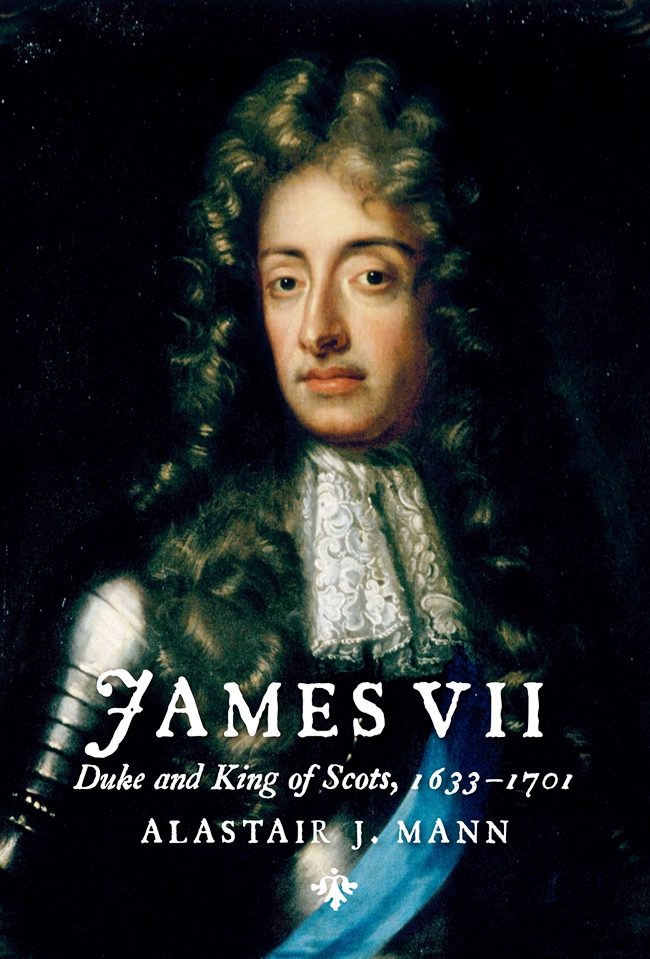

JAMES VII

JAMES VII

DUKE AND KING OF SCOTS

ALASTAIR J. MANN

John Donald

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

ISBN: 978 1 904607 90 8

eISBN: 978 1 907909 09 2

Copyright Alastair J. Mann 2014

The right of Alastair J. Mann to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The publishers gratefully acknowledge the support of the Scouloudi Foundation towards the publication of this book

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh Printed and bound in the UK by Bell and Bain Ltd, Glasgow

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

T his study has been one of long gestation and as such there are many individuals and institutions to thank for their patience and encouragement. Worthy of commendation are numerous archivists and librarians, including the staff of the National Archives of Scotland (now the National Records of Scotland); the Scottish National Library; the National Archives at Kew; The British Library; Dr Williams Library; Bodleian Library, Oxford; Scottish Catholic Archives (visited at its spiritual home of Columba House, Edinburgh), and the Royal Archives at Windsor, where Allisson Derrett was particularly helpful. I am especially grateful to Lady Dunmore and John Douglas Stuart, 21st earl of Moray, for permissions to consult and quote from family papers. Particular acknowledgment is due to the late, ninth Duke of Buccleuch for granting permission to visit the Queensberry archives at Drumlanrig Castle and also to his then archivist Andrew Fisher for guiding me through the large collection. I gratefully acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to consult and quote material from the Stuart Papers in the Royal Archives. Additional permission for the use of pictures from the Royal Collection is also recognised and is specified, along with other permissions, in the separate list of figures.

Intellectual help has been provided by a number of current and former colleagues. A particular debt is owed to Professor Keith Brown at Manchester University, formerly of the Scottish Parliament Project at St Andrews University, for encouragement and guidance in ways mostly unbeknownst to him, and also to patient colleagues at Stirling University, led by Professor Richard Oram, who like many a student, have had to live with the long-term obsession of the biographer. My thanks to the School of Arts and Humanities at Stirling for sporadic but vital research time to complete the archival work and actual writing. I must thank Dr Mike Rapport for very accurate French translations. For assistance with the cost for research trips to Paris, Oxford and London I must thank the Strathmartine Trust for a generous grant. This publication has been made possible by a grant from the Scouloudi Foundation in association with the Institute of Historical Research.

The thanks owed to my family defeats calculation. My sons, Robert and Andrew, have looked on bemusedly over the years and have allowed me to keep my sense of humour. My mother Anna has encouraged with her genuine interest. As for my wife Lesley, she has had to put up with many hardships during the intellectual and practical journey that is the fate of the biographer. I love you all.

AM

Introduction: A Contested Reputation

J ames VII of Scotland and II of England (16331701) is one of the most controversial historical characters of the early modern period. He is a reference point for historical assessment in a range of thematic fields including, to mention but some, the Restoration of the British monarchy from 1660, the Glorious Revolution of 1688/9, the fiscal-military state, the European Nine-Years War (168997), the age of absolutism, the Ancien Regime, and the beginnings of Jacobitism as it unfolded from 1689 to 1746. Perhaps it is for this reason that some of his biographies creak under the weight of the task before them and why no Scottish life has so far been attempted.

The study of King James is not merely multi-faceted but quite perplexing. Too often chapter titles such as rise and fall and study in failure are suggested by a life with many fits and starts. As we shall see, he achieved an almost unbroken string of military and naval successes from 1652 to 1672, although in contrast to later reverses and humiliations. To quote a tepid comment from Jamess autobiography which survives through J. S. Clarkes The Life of James the Second (1816) and is the nearest thing we have to a memoirs, based as it is on a manuscript compilation of his own writings his life was made up of mortifications and crosses, so even the few satisfactions he had, were seldom without a mixture of disappointments.Had James not survived his brother Charles II (16301685) his reputation would have been secured as an honourable military man and not as a Catholic monarch with perceived and sometimes stumblingly real inclinations towards absolutism.

There is, however, some consensus among Whig and Tory historiography on the scale of Jamess political shortcomings, with differences focusing on where weaknesses developed or our subjects personal motivations. These commentators, who look more to parliaments and the Crown respectively, often arrive at similar conclusions by separate paths. The contemporary Whig historian Bishop Gilbert Burnet, an Anglo-Scot who focused mostly on English affairs, led the accusation that James sought to undermine the English constitution in a drive for absolute power. The Revolution that followed this was therefore a constitutional rebalancing. Lord Macaulay, the nineteenth-century grandee of English history, took this same line, as did Trevelyan and others into the twentieth century. Meanwhile, the eighteenth-century historian Edmund Burke, mostly Whig in politics but Tory in much of his history, stressed religion in combination with constitutionalism. Jamess Catholicism led to a crisis and the Revolution was necessary only to correct that misalignment and, yes, to put back in place Parliament, but also the central role of right kingship. As this biography reveals, however, elite groups in early modern Scotland exercised both political and religious motivations in equal measure, as did James himself.

While there are no existing Scottish biographies of King James, those of him as king of England are numerous and provide a firm foundation. One remarkable tour de force of the mid twentieth century is F. C. Turners biography which sparkles with detail, brilliant analytical moments but a familiar Whig-like prejudice. Turner also bridged the two phases of Jamess life. His seeming transformation, hinged at 1685 when he became king and moved from energetic and competent Importantly, and convincingly, Callow rejects the degeneration theory: the same man was the dashing young prince as the defeated old king, and the seeds of Jamess failures were planted in the period of his youth.