Contents

David Womersley

JAMES II

The Last Catholic King

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2015

Copyright David Womersley, 2015

Cover design by Pentagram

Jacket art by Gisela Goppel

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-141-97707-2

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

Penguin Monarchs

THE HOUSES OF WESSEX AND DENMARK

| Athelstan | Tom Holland |

| Aethelred the Unready | Richard Abels |

| Cnut | Ryan Lavelle |

| Edward the Confessor | James Campbell |

THE HOUSES OF NORMANDY, BLOIS AND ANJOU

| William I | Marc Morris |

| William II | John Gillingham |

| Henry I | Edmund King |

| Stephen | Carl Watkins |

| Henry II | Richard Barber |

| Richard I | Thomas Asbridge |

| John | Nicholas Vincent |

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

| Henry III | Stephen Church |

| Edward I | Andy King |

| Edward II | Christopher Given-Wilson |

| Edward III | Jonathan Sumption |

| Richard II | Laura Ashe |

THE HOUSES OF LANCASTER AND YORK

| Henry IV | Catherine Nall |

| Henry V | Anne Curry |

| Henry VI | James Ross |

| Edward IV | A. J. Pollard |

| Edward V | Thomas Penn |

| Richard III | Rosemary Horrox |

THE HOUSE OF TUDOR

| Henry VII | Sean Cunningham |

| Henry VIII | John Guy |

| Edward VI | Stephen Alford |

| Mary I | John Edwards |

| Elizabeth I | Helen Castor |

THE HOUSE OF STUART

| James I | Thomas Cogswell |

| Charles I | Mark Kishlansky |

| [Cromwell | David Horspool] |

| Charles II | Clare Jackson |

| James II | David Womersley |

| William III & Mary II | Jonathan Keates |

| Anne | Richard Hewlings |

THE HOUSE OF HANOVER

| George I | Tim Blanning |

| George II | Norman Davies |

| George III | Amanda Foreman |

| George IV | Stella Tillyard |

| William IV | Roger Knight |

| Victoria | Jane Ridley |

THE HOUSES OF SAXE-COBURG & GOTHA AND WINDSOR

| Edward VII | Richard Davenport-Hines |

| George V | David Cannadine |

| Edward VIII | Piers Brendon |

| George VI | Philip Ziegler |

| Elizabeth II | Douglas Hurd |

1

The Varieties of Whig History

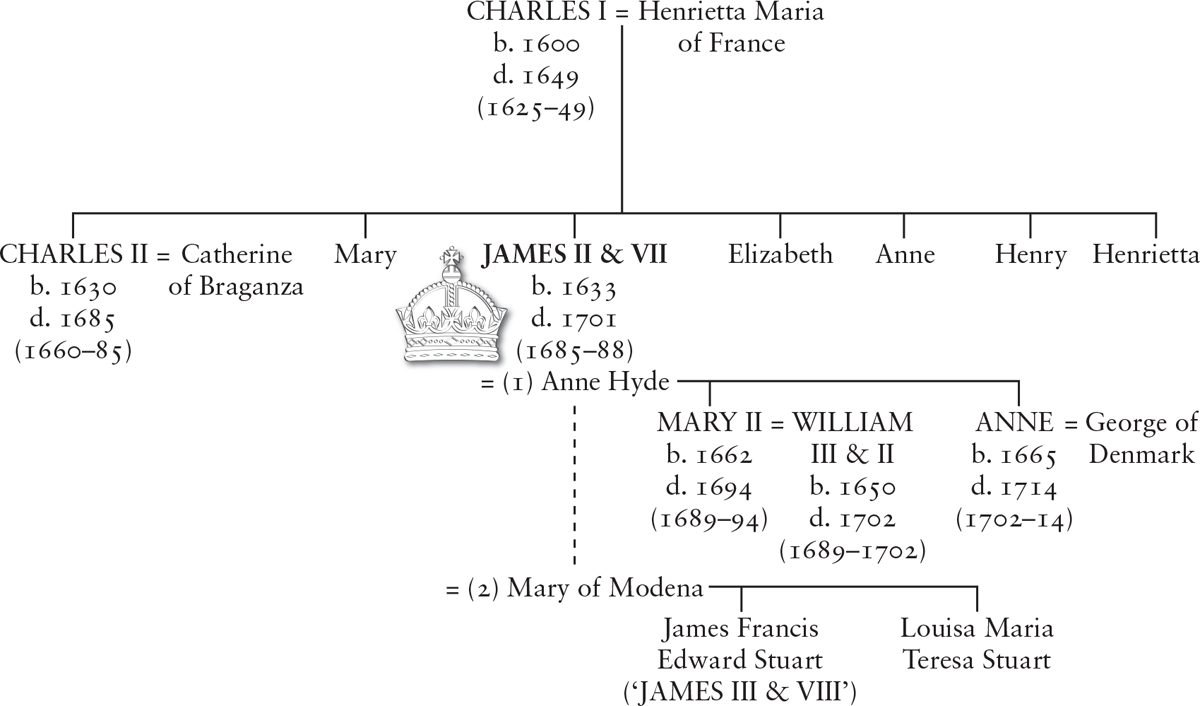

James II reigned for less than four years, from February 1685 to November 1688. Yet his short reign was one of the great pivots of English constitutional history. James ascended the throne with the formidable prerogative powers of the Stuart monarchy intact, and with Parliament as still a junior partner in the governance of the realm (Parliament had met for only eleven of the first forty years of the seventeenth century). After 1688 the prerogative powers of the crown, although still considerable, were acknowledged to be subject to parliamentary curbs. Furthermore Parliament itself had been transformed from an event into an institution, becoming a permanent part of the constitution, and one which met regularly.

If Jamess brief reign was momentous in its political consequences at the time and during the following decades, it has for later generations proved to be no less of a battleground in English historiography. In 1931 the Cambridge historian Herbert Butterfield famously took aim at what he However, it would be a mistake to think that there was only one kind of Whig Interpretation of the reign of James II. To pause for a moment over the different kinds of Whig historiography will bring out the key issues which any account of the years 16858 must address.

Nine days after his defeat at the Battle of the Boyne the exiled James II landed at Brest and immediately began trying to persuade Louis XIV to entrust him with another army for the reconquest of his lost kingdoms. The campaign in Ireland, he urged, had depleted England of troops. Nothing could now withstand French forces, and furthermore his contrite people were eager to make amends for the disloyalty and ingratitude they had shown to their rightful monarch.

Louis was too polite to utter an outright refusal, but he was also resolved not to accede to Jamess request, and so he feigned illness in order that the unpleasant subject could not be raised. Macaulay describes the undignified position in which this left James:

During some time, whenever James came to Versailles, he was respectfully informed that His Most Christian Majesty was not equal to the transaction of business. The highspirited and quickwitted nobles who daily crowded the antechambers could not help sneering while they bowed low to the royal visitor, whose poltroonery and stupidity had a second time made him an exile and a mendicant. They even whispered their sarcasms loud enough to call up the haughty blood of the Guelphs in the cheeks of Mary of Modena. But the insensibility of James was of no common kind. It had long been found proof against reason and against pity. It now sustained a still harder trial, and was found proof even against contempt.

This portrait of James as a man both stupid and despicable is a dominant feature of Macaulays History of England, which throughout lays a heavy emphasis on Jamess incurable faults of head and heart. Jamess Declaration of 1692 a document consisting largely of lists of those of his former subjects, some designated by name, others designated more generally by reference to particular failures of conduct, who were to expect no mercy in the event of his restoration Macaulay regarded as entirely characteristic: the whole man appears without disguise, full of his own imaginary rights, unable to understand how any body but himself can have any rights, dull, obstinate and cruel.