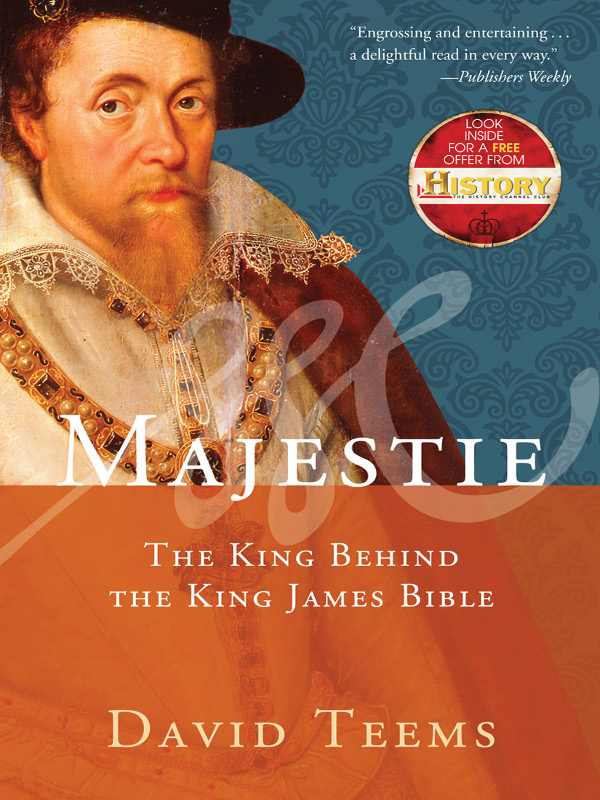

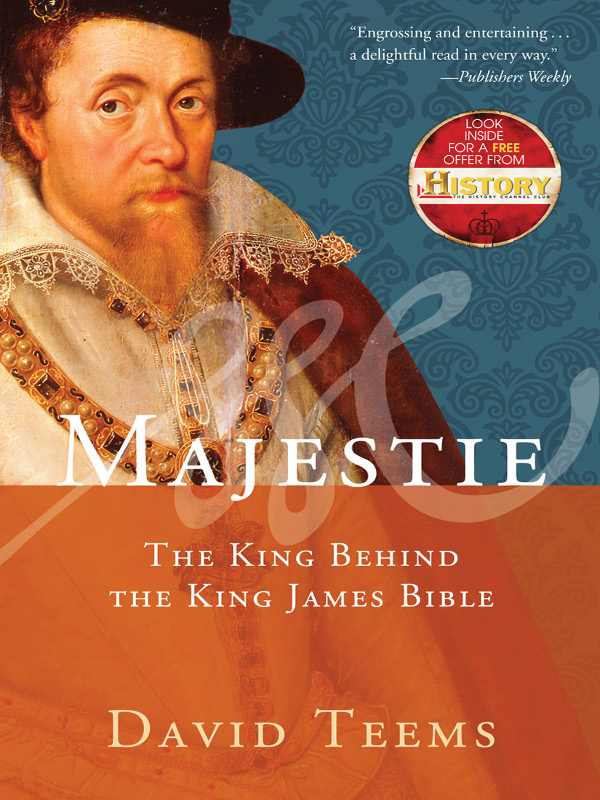

MAJESTIE

MAJESTIE

THE KING BEHIND

THE KING JAMES BIBLE

DAVID TEEMS

2010 by David Teems

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Published in association with Rosenbaum & Associates Literary Agency, Brentwood, Tennessee.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fundraising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Teems, David.

Majestie : the king behind the King James Bible / By David Teems.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59555-220-4 (alk. paper)

1. James I, King of England, 1566-1625. 2. Great BritainHistoryJames I, 16031625. 3. Great BritainKings and rulersBiography. 4. ScotlandHistoryJames VI, 15671625. 5. ScotlandKings and rulersBiography. I. Title.

DA391.T44 2010

941.06'1dc22

2010020907

Printed in the United States of America

10 11 12 13 RRD 6 5 4 3 2 1

To be a king and wear a crown is a thing

To be a king and wear a crown is a thing

more glorious to them that see it than it is

pleasant to them that bear it.

ELIZABETH I OF ENGLAND

FOR ALL LOST BOYS

Contents

Contents

Prologue: For a Pennys Worth of Hamlet

20 Finishing Touches

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

For a Pennys Worth

of Hamlet

1603. There is a discernable hum about the city. The swarm and tread of a long forgotten life, a life far removed from our owna large, teeming, and animated life, fluid, and slightly opaque, like the Thames that winds ventricle-like through its heart. The market at Smithfield is effuse with a smell that might be burnt brick, tallow, or sea coal. The slow moan and shuttle of livestock. There are the alehouses and ladies of sale. The bear-baiting precincts of Southwark and the great Globe itself, pulsing with life deep in the afternoons. The bustle of theatre cues for a pennys worth of Hamlet.

Her language is as alive as her streets, as deathless and penetrating as the smell, as opulent and full of pomp as the fashions they wearthe silk, the lace, the excess, the ornament. Her English is without rule or harness, feral, wanton, a hungry creature. And she purrs in the hands of her masters.

This is early modern London, the London of Shakespeare and John Donne, of Francis Bacon and Sir Walter Raleigh, of Sir John Falstaff and Mistress Quickly, of the Mermaid Tavern and Puddle Dock, of Fleet Street and Pudding Lane. That filthie toune, as the new Stuart king would come to call it.

It is a lyrical age, the age of the sonnet and the rhymeless pentameter, of pamphleteers and playmakers, of three-hour sermons and two-hour plays. Of severed and unsmiling heads mounted aloft the parapets of London Bridge. An age of child kings, and the pox.

Religion can be dangerous, and spelling is a matter of taste.

And rising out of the clamor, out of the fogs and charred winds, comes her king, our king, as we will refer to him, born some four hundred miles to the north, born in a mask, a man more to be pitied than admired, more to be mocked than loved, a man who sleeps with sermons under his pillow. A prince to be feared indeed, but only for his distractions, for his precarious and bungling politics, and perhaps his bad manners.

But like the tragic Lear, he is every inch a king.

Truth is, I have no idea what the market at Smithfield was like, or any other London marketplace for that matterthe smell, the movement of traffic, if it hummed or whined. As animated as the above text may be, as alive and as effervescent as any treatment of Elizabethan London should be, as convincingly as I can ever hope to express it, it is an interpretation, a reckoning by way of story. At such a distance, it can hardly be anything else. It is a distillation of sources I have plundered, a kind of translation, I suppose, and as any translation does, it clarifies and teaches us how to perceive. The preface to the 1611 King James Bible says it this way:

Translation it is that openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most Holy place.

The King James I went looking for was not the King James I found. I went looking for the buffoon, for the jester, the lottery winner who came riding into town in a golden pumpkin, the spoiled boy who could not possibly have replaced the great Elizabeth.

I went looking for the Scot whose tongue was too big for his mouth, who dribbled when he drank, who drank too often, and waddled when he walked even when sober. I went looking for the caricature, for the Saturday morning cartoon. What I found was an uncouth, improbable, and yet somehow enchanting king.

I found all the other as well. With a few exceptions, James is all of that. He is as good as any play. He is an entire theater. And for all the fascination with his mother, the Queen of Scots, or his English predecessor, Elizabeth, or any one of the great spirits that trafficked the age, it is James who fascinates me.

It is not enough to salute King James as an original he was also one of the most complicated neurotics ever to sit on either the English or Scottish throne.

It is not enough to salute King James as an original he was also one of the most complicated neurotics ever to sit on either the English or Scottish throne.

G. P. V. AGRIGG,

LETTERS OF KING

JAMES VI & I

The life of James Stuart is a study in contradiction. Intellectually astute, he can dazzle with the polish of his rhetoric one minute, and speak with the vulgarity of a tavern bawd the next. Speaking Latin and Greek before he was five, King James is an amusing mix of bombast and imperium, of sparkle and grime, of smut and brilliance, of visionary headship and blunder.

He wasnt much to look at either. His parents were beautiful, stormy. He was James. Like them, he might have been taller had his body been a bit straighter or the plumb of his legs a little truer. We might imagine the young king with his hands on his hips (a pose he liked), his great hat on his head at a fashionable tilt, a lack of shine on his boots, as he appeared when he first saw Anne of Denmark. Like me, she didnt know what to make of him at first.

We call it the Jacobean Age because the Latin form of James is Iacobus , that is, Jacob ( Ya`aqob yah-ak-obe' [Hebrew];

Ya`aqob yah-ak-obe' [Hebrew];  Iakob ee-ak-obe' [Greek]). The biblical Jacob was a twin. He was a dissembler, a man of cunning, a creature of artifice who was chosen to father a great people. I am not sure there could be a more appropriate name.

Iakob ee-ak-obe' [Greek]). The biblical Jacob was a twin. He was a dissembler, a man of cunning, a creature of artifice who was chosen to father a great people. I am not sure there could be a more appropriate name.

Next page

To be a king and wear a crown is a thing

To be a king and wear a crown is a thing

It is not enough to salute King James as an original he was also one of the most complicated neurotics ever to sit on either the English or Scottish throne.

It is not enough to salute King James as an original he was also one of the most complicated neurotics ever to sit on either the English or Scottish throne. Ya`aqob yah-ak-obe' [Hebrew];

Ya`aqob yah-ak-obe' [Hebrew];  Iakob ee-ak-obe' [Greek]). The biblical Jacob was a twin. He was a dissembler, a man of cunning, a creature of artifice who was chosen to father a great people. I am not sure there could be a more appropriate name.

Iakob ee-ak-obe' [Greek]). The biblical Jacob was a twin. He was a dissembler, a man of cunning, a creature of artifice who was chosen to father a great people. I am not sure there could be a more appropriate name.