The Glorious History of the English Bible

Copyright 2006 by David Cloud

Updated November 14, 2008

Third edition February 10, 2016

ISBN 1-58318-096-6

Published by Way of Life Literature

P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061

866-295-4143 (toll free) fbns@wayoflife.org

http://www.wayoflife.org

Canada: Bethel Baptist Church,

4212 Campbell St. N., London, Ont. N6P 1A6

519-652-2619

Printed in Canada by

Bethel Baptist Print Ministry

Introduction

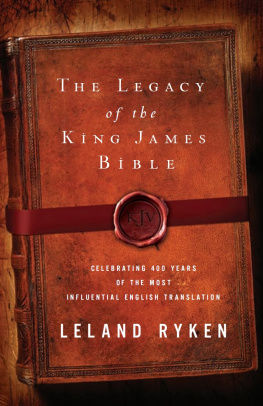

The King James Bible is not merely another translation. Its heritage and the manner in which it was created are unique.

The early record of the English Bible is one of the most fascinating chapters of church history and reads almost like a novel.

The history of the British Empire and of the American nation and of the English language itself are inextricably intertwined with the King James Bible.

The Glorious Heritage of the King James Bible recounts this history, beginning with the Wycliffe Bible of the late 14th century.

Every English-speaking believer should know this history; yet, sadly, even in the staunchest Bible-believing churches it is rare to find someone who is well informed about the great price that was paid to provide us with such an excellent Bible in our own language.

I have studied this history for many years, not only through literature (having built a large and expensive personal library on this subject) but through onsite research in the places where the history took place. By Gods grace Ive traveled to Lutterworth and Oxford and Cambridge, to Little Sodbury Manor and St. Adelines Church and St. Dunstans and Fulham Palace, to Smithfield and Hampton Court and Westminster and the Jerusalem Chamber, to Lambeth Palace and the Lollards Tower and St. Pauls Cathedral, to Vilvoorde and Geneva. Ive handled ancient Waldensian New Testaments at the Cambridge Library and Trinity College Dublin and early edition Tyndale Bibles at the British Museum.

This fascinating research has greatly strengthened my faith in God and in the authenticity and preservation of His holy Word, and I trust that The Glorious Heritage of the English Bible will do the same for each reader of this book.

The Wycliffe Bible (1380, 1382)

The history of the English Bible properly begins with John Wycliffe (1324-1384).

The Scriptures most commonly found among English people before Wycliffe were Anglo Saxon and French, and the few English translations were only of portions of Scripture. (For an examination of the history of the Bible in England prior to Wycliffe see Faith vs. the Modern Bible Versions , available from Way of Life Literature.)

Some modern scholars have tried to make the case that Wycliffe did not do any of the actual translation himself, but older historians did not question Wycliffes role in the work and we believe the evidence supports their view. That Wycliffe had helpers and that the original translation went through revisions no one doubts, but I do not accept the position that John Wycliffe was not involved in the actual translation.

Wycliffes Times

In John Wycliffes day Rome ruled England and Europe with an iron fist. By the 7th century, Rome had brought England under almost complete dominion, and it was under subjugation to the popes from then until the 16th century, roughly 900 years, a period that is called Britains Dark Ages.

King John (who ruled from 1199-1216) tried to resist Pope Innocent IIIs authority in the early 13th century, but he was not successful.

The pope excommunicated John and issued a decree declaring that he was no longer the king and releasing the people of England from their obligation to him. The pope ordered King Philip of France to organize an army and navy to overthrow John, which he began to do with great zeal, eager to conquer England for himself. The pope also called for a crusade against John, promising the participants remission of sins and a share of the spoils of war. Bowing to this pressure, John submitted to the pope, pledging complete allegiance to him in all things and resigning England and Ireland into the popes hands. The following is a quote from the oath that John signed on May 15, 1213:

I John, by the grace of God King of England and Lord of Ireland, in order to expiate my sins, from my own free will and the advice of my barons, give to the Church of Rome, to Pope Innocent and his successors, the kingdom of England and all other prerogatives of my crown. I will hereafter hold them as the popes vassal. I will be faithful to God, to the Church of Rome, to the Pope my master, and to his successors legitimately elected.

The Roman Catholic authorities severely repressed the people and did not allow any form of religion other than Romanism. There was intense censorship of thought. Those who refused to follow Catholicism were persecuted, banished, and even killed.

The popes representatives had great authority and held many of the highest secular offices in the land.

The higher dignitaries in both these classes of the clergy, by virtue of their great temporalities held in feudal tenure from the crown, were barons of the realm, and sat in parliament under the title of lords spiritual, taking precedence in rank for a parliament, archbishops, bishops, and abbots already headed the list. By prescriptive right, derived from times when the superior intelligence of the clergy gave them some claim to the distinction, all the high offices of state, all paces of trust and honor about the court, were in the hands of the clergy. In 1371, the offices of Lord Chancellor, Lord Treasurer, Keeper and Clerk of the Privy Seal, Master of the Rolls, Master in Chancery, Chancellor and Chamberlain of the Exchequer, and a multitude of inferior offices, were all held by churchmen (H.C. Conant, The Popular History of the Translation of the Holy Scriptures , revised edition, 1881, p. 11).

The bishops, parish priests, and even the monks in the monasteries lived in great opulence through the accumulation of property, the ingathering of tithes and offerings, the saying of masses for the dead, and the sale of indulgences.

To the office of the prelates were attached immense landed estates, princely revenues and high civil, as well as ecclesiastical powers; the lower clergy, residing on livings among the people, were supported chiefly by tithes levied on their respective parishes. The wealth of the English monks at this period almost passes belief. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the endowment of monasteries was a mania in Christendom. Lands, buildings, precious stones, gold and silver, were lavished upon them with unsparing prodigality. Rich men, disgusted with the world, or conscience-striken for their sins, not unfrequently entered the cloister and made over to it their whole property. During the crusading epidemic, many mortgaged their estates to the religious houses for ready money, who never returned, or were too much impoverished to redeem them. In this way vast riches accrued to their establishments. They understood, to perfection, all of the traditional machinery of the Church for extracting money from high and low. The exhibition of relics, the performance of miracles, and above all the sale of indulgences, and of masses for the dead, formed an open sluice through which a steady golden stream poured into the monastic treasury (Conant, Popular History of the Translation , pp. 5, 8).

All orders of Roman Catholic clergy were exempt from civil jurisdiction and could provide a safe haven for criminals.