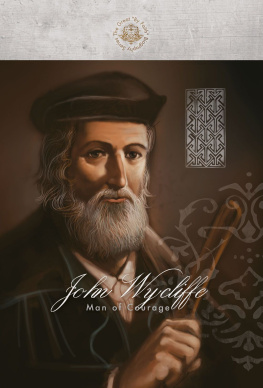

John Wycliffe:Man of Courage

First printing, 2004

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design & page layout by A & E Media Paula Shepherd

Cover illustration by Portland Studios Justin Gerard

Edited by Rebecca Hammond

ISBN: 978-1-93230-727-6

eISBN: 978-1-88989-376-1

Published by the Ambassador Group

Ambassador Emerald International

427 Wade Hampton Blvd.

Greenville, SC 29609USA

www.ambassador-international.com

and

Ambassador Publications Ltd.

Providence House

Ardenlee Street

Belfast BT6 8QJNorthern Ireland

www.ambassadormedia.co.uk

The colophon is a trademark of Ambassador

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1

Papal England

We wait for light, but behold obscurity; for brightness, but we walk in darkness. ~Isaiah 59:9

IN THE MIDDLE AGES AMIDST the nations of Europe, two powers contended for supremacythe Pope and the King.

The Pope, as the Vicar of Jesus Christ, first assumed the title of Universal Bishop, and afterwards claimed temporal dominion over all the monarchs of Christendom. Long and fierce struggles ensued in consequence of this claim, and much blood was shed. In some countries the strife was carried on for centuries, but in England it was happily terminated at an early period. The great man, to whose wisdom, patriotism, and piety the nation mainly owes this happy result, was John Wycliffe.

In the early years of the thirteenth century, the kingdom of England became subject to the Pope. A dispute had arisen between King John and the canons of Canterbury concerning the election of an archbishop for that diocese, in place of Hubert, who died in 1205. Both the canons and the king appealed to the Pope, and sent agents to Rome. The pontifical chair was then filled by Innocent III, who, like his predecessor, Gregory VII, was vigorously striving to subordinate the rights and powers of princes to the Papal See, and to take into his own hands all the ecclesiastical appointments of the Christian nations, so that through the bishops and priests he might govern at his will all the kingdoms of Europe.

Innocent annulled both the election of the canons and also that of the king, and caused his own nominee, Cardinal Langton, to be chosen to the see of Canterbury. But, more than this, he claimed the right for the Pontiff of appointing to this seat of dignity for all coming time.

John was enraged when he saw this action taken by the Pope. If he now appointed to the see of Canterbury, the most important dignity in England save the throne, would he not also appoint to the throne itself? The king protested with many oaths that the papal nominee should never sit in the archiepiscopal chair. He turned the canons of Canterbury out of doors, ordered all the prelates and abbots to leave the kingdom, and bade defiance to Rome. Innocent III smote England with interdict. The church doors were closed, the lights at the altars were extinguished, the bells ceased to be rung, the crosses and images were taken down and laid on the ground, infants were baptized in the church porch, marriages were celebrated in the churchyard, the dead were buried in ditches or in the open fields. No one dared rejoice, or eat flesh, or shave his beard, or pay any decent attention to his person or apparel. It was appropriate that only signs of distress, mourning, and woe should be visible throughout a land over which there rested the wrath of the Almighty--for so did the men of those days account the ban of the Pontiff.

King John braved this state of things for two years, when Innocent pronounced sentence of excommunication upon him, absolving his subjects from their allegiance, and offering the crown of England to Philip Augustus, King of France. Philip collected a mighty armament, and prepared to cross the Channel and invade the territories of the excommunicated king.

At this time John was on bad terms with his barons on account of his many vices, and dared not depend upon their support. He saw the danger in which he stood, and, losing what little courage he possessed, determined upon an unconditional surrender to the Pope. He claimed an interview with Pandolf, the papal legate, and, after a short conference, engaged to make full restitution to the clergy for the losses they had suffered. He then resigned England and Ireland to God, to St. Peter and St. Paul, and to Pope Innocent and his successors in the apostolic chair, agreeing to hold these dominions as feudatory of the Church of Rome, by the annual payment of a thousand marks; also stipulating that if he or his successors should ever presume to infringe this charter, they should instantly, except upon admonition they repented of their offense, forfeit all right to their dominions.

The transaction was ended by the King of England kneeling before the legate of the Pope, and, taking the crown from his head, offering it to Pandolf, saying, Here I resign the crown of the realm of England into the Popes hand, Innocent III, and put me wholly in his mercy and ordinance.

This event occurred on May 15, 1213, and never has there been a moment of more profound humiliation for England.

This dastardly conduct on the part of their king aroused the patriotism of the nation. The barons determined that they would never be the slaves of a Pope, and, unsheathing their swords, they vowed to maintain the ancient liberties of England or die in the attempt. On June 15, 1215, they compelled John to sign Magna Charta at Runnymede, and thus in effect to tell Innocent that he revoked his vow of vassalage, and took back the kingdom which he had laid at his feet. The Pope was furious. He issued a bull declaring that he annulled the charter, and proclaiming all its obligations and guarantees void.

From this reign England may date her love of liberty and dread of popery. At its commencement the distinction that had existed since the conquest between Norman and Saxon was broadly marked, and the Norman baron looked upon his Saxon neighbor with contempt, his common form of indignant denial being, Do you take me for an Englishman? Towards its close there was a drawing together of the two races, and from their amalgamation was afterwards formed the bold and strong English people, who, in the fourteenth century, offered so stout a resistance to the arrogant claims of the Roman See.

But, while feeling a dread of the papacy, the people still held to the doctrines of Rome. Enveloped in ignorance and sunk in social degradation and vice, they had not the Scripture to enlighten their path. The Bible was a sealed book. Freedom of conscience was denied, and the religion of the country consisted in outward ceremonials, appealing to the senses but not influencing the heart. DAubign, the historian of the Reformation, states, Magnificent churches and the marvels of religious art, with ceremonies and a multitude of prayers and chantings, dazzled the eyes, charmed the ears, and captivated the senses, but testified also to the absence of every strong moral and Christian disposition, and the predominance of worldliness in the Church. At the same time, the adoration of images and relics, saints, angels, and Mary, the mother of God, transporting the real Mediator from the throne of mercy to the seat of vengeance, at once indicated and kept up among the people that ignorance of truth and absence of grace which characterize popery.