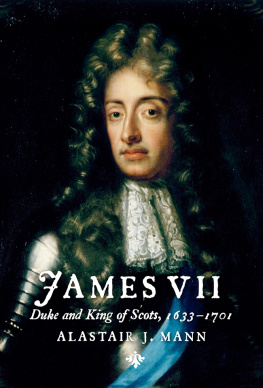

About the Book

As the son of Mary Queen of Scots, James had the most precarious of childhoods. By the time James was one year old, his father was murdered, possibly with the connivance of his mother; Mary was in exile in England; and James was King of Scotland. By the age of five, he had experienced three different regents as the ancient dynasties of Scotland battled for power. For the rest of his life, he would be caught up in bitter struggles between the warring political and religious factions.

Yet Jamess caution and politicking won him the English throne on Elizabeths death in 1603 and he rapidly set about trying to achieve the Union of the two kingdoms. Alan Stewarts impeccably researched new biography makes brilliant use of original sources to bring to life the conversations and the controversies of the Jacobean age. In doing so, he uncovers the extent to which Charles Is downfall was caused by the cracks that appeared in the monarchy during his fathers reign.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781448104574

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Pimlico 2004

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3

Copyright Alan Stewart 2003

Alan Stewart has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in Great Britain by

Chatto & Windus 2003

Pimlico edition 2004

Pimlico

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SWIV 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Limited

18 Poland Road, Glenfield,

Auckland 10, New Zealand

Random House South Africa (Pty) Limited

Isle of Houghton, Corner of Boundary Road & Carse OGowrie,

Houghton 2198, South Africa

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780712667586 (from Jan 2007)

ISBN 0-7126-6758-X

www.vintage-books.co.uk

Contents

About the Author

Alan Stewart is the author of the acclaimed biographies Philip Sidney: A Double Life and Hostage to Fortune: The Troubled Life of Francis Bacon (with Lisa Jardine). He is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, and Associate Director of the AHRB Centre for Editing Lives and Letters in London. He lives in New York City.

Acknowledgements

Work on this book started at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC and finished at the British Library in London, and I am indebted to the librarians and staff of both these great institutions. I am immensely grateful to the Folger for giving me a Short-Term Fellowship in 2000, and to Tom Healy and my colleagues at Birkbeck for allowing me generous research leave. Maggie Pearlstine and John Oates at Maggie Pearlstine Associates encouraged me throughout. At Chatto & Windus, Rebecca Carter was a supportive and challenging editor.

I could not have written The Cradle King without the insights of those scholars who have broadened and deepened our knowledge of all things Jacobean since D.H. Willsons 1956 biography of James. I learned particularly from the work of (in alphabetical order) G.P.V. Akrigg, Leeds Barroll, David Bergeron, Caroline Bingham, Antonia Fraser, Jonathan Goldberg, Maurice Lee Jr., Roger Lockyer, Maureen Meikle, Stephen Orgel, Curtis Perry, David Stevenson, Roy Strong and Jenny Wormald. For ideas, suggestions, comments and help of many kinds, I am grateful to Tom Betteridge, Warren Boutcher, Tricia Bracher, Jerry Brotton, Stephen Clucas, Erica Fudge, Donna Hamilton, James Knowles, Gordon McMullan, Steven May, David Norbrook, Alex Samson, James Shapiro, Bruce Smith, Sue Wiseman, Heather Wolfe and Elizabeth Wood.

Finally, my sincere thanks go to the friends who saw me through: Patricia Brewerton, James Daybell, Will Fisher, Eliane Glaser, Andrew Gordon, Lisa Jardine, Simon Lloyd-Owen, Lloyd Meiklejohn, Kirk Melnikoff, Chris Ross, Richard Schoch, Goran Stanivukovic, Garrett Sullivan and especially Tyler Smith.

List of Illustrations

Prologue

IN 1603, JAMES I, King of England, made a visit to one of the most southerly of his new possessions, Beaulieu, in the New Forest. All the local nobility and gentry turned out to get their first glimpse of the King of Scots who had just become their own sovereign. Among them was the eighteen-year-old John Oglander, a son of the local landed gentry. Over fifty years later, Oglander jotted down his memories of that royal visit. By then, his life was consumed by the fight to save Jamess son, the embattled King Charles. But his image of James was far from complimentary. King James I of England was the most cowardly man that ever I knew, he started. When James came to Beaulieu, he recalled, he was much taken with seeing the little boys skirmish, whom he loved to see better and more willingly than men. The pantomime of juvenile combat suited the King far better than the real, very bloody thing. He could not endure a soldier or to see men drilled, to hear of war was death to him, and how he tormented himself with fear of some sudden mischief may be proved by his great quilted doublets, pistol-proof, was also his strange eyeing of strangers with a continual fearful observation.

Why would Oglander, a staunch royalist, write such a thing? His other notes on the King were positive enough. Otherwise, he wrote, James was the best scholar and wisest prince for general knowledge that ever England had, very merciful and passionate, liberal and honest. He was a great politician and very sound in the reformed religion. He spoke much and as well as any man, or rather better. And he was the chastest prince for women that ever was, for he would often swear that he had never known any other woman than his wife. Although he was known to be excessively taken with hunting indeed, he was notorious for it he did not, or could not, according to Oglander, use much bodily action, so that his body for want of use grew defective. In Oglanders eyes, this was a King for whom theory and rhetoric were never matched by practice. If he had but the power, spirit and resolution to have acted that which he spoke, or done as well as he knew how to do, Solomon had been short of him.

For Oglander, the answer to this paradox lay in the Kings fearful nature. Throughout his life, James was noted, and lampooned, for his fear of war, weapons, loud noises and unexplained strangers. He referred to them, in his usual grandiose style, as his daily tempests of innumerable dangers. Speaking to the English Parliament after he survived perhaps the greatest threat of all, the Gunpowder Plot of November 1605, he made his own diagnosis as to the cause of his fearful nature. They could be traced and dated, he told the Parliament, not only ever since my birth, but even as I may justly say, before my birth: and while I was in my mothers belly.