Ignorance

Literature and Agnoiology

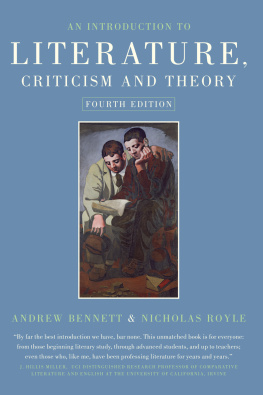

Andrew Bennett

Copyright Andrew Bennett 2009

The right of Andrew Bennett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK

and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

Distributed in the United States exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,

NY 10010, USA

Distributed in Canada exclusively by

UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall,

Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 0 7190 7487 5

First published 2009

18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or any third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Florence Production Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon

Printed in Great Britain

by CPI Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Contents

Acknowledgements

My thanks are due to the Arts and Humanities Research Council and to my colleagues in the English Department at the University of Bristol for enabling me to take a period of research leave in order to write this book. A number of chapters have previously been published in earlier forms: as Authorial Ignorance: Philip Roths American Trilogy, in Tekijyyden Ulottuvuuksia (Dimensions of Authorship), ed. Eeva Haverinen, Erkki Vainikkala and Tuomo Lahdelma (Jyvskyl: Jyvskyln Yliopisto, 2008), pp. 91114. I would like to thank the editors for permission to reprint this material here.

Ignorance is not just a blank space on a persons mental map. It has contours and coherence, and for all I know rules of operation as well. (Thomas Pynchon, Introduction to Slow Learner)

[Y]ou can take interest in what I am doing here only insofar as you would be right to believe that somewhere I do not know what I am doing. (Jacques Derrida, Glas)

Reading demands more ignorance than knowledge. (Maurice Blanchot, The Space of Literature)

In a manner that is more acute for theoreticians of literature than for theoreticians of the natural or the social world, it can be said that they do not quite know what it is they are talking about, not only in the metaphysical sense that the whatness, the ontology of literature is hard to fathom, but also in the more elusive sense that, whenever one is supposed to speak of literature, one speaks of anything under the sun (including, of course, oneself) except literature. (Paul de Man, The Resistance to Theory)

Introduction

This book concerns the way in which literature, particularly as it is defined at a certain historical moment, is bound up with the question of not knowing. And it concerns the question of what literature knows of ignorance. If a narrative is something told, Stanley Cavell speculates very generally in Disowning Knowledge, and telling is an answer to a claim to knowledge, then perhaps any narrative, however elaborated, may be understood as an answer to some implied question of knowledge, perhaps in the form of some disclaiming of knowledge or avoidance of it. In this context I will suggest that ignorance may be reconceived as part of the narrative and other force of literature, part of its performativity, and indeed as an important aspect of its thematic focus what literary texts are about. Concentrating in particular on the Romantic and post-Romantic tradition, I seek to address the question of literary ignorance by attempting to work through some of the consequences of the question of not knowing for our reading of such texts.

The book is also concerned with certain formal, technical, generic and historical questions: with the presentation of both authors and readers as, in their different ways, constitutionally, necessarily ignorant; with the ways in which the formal and indeed linguistic resources of a literary text might resist hermeneutic exegesis (ways in which such a text might resist knowledge, resist our knowing, in that sense); with questions of the novelistic and poetic specificities of ignorance; and with the constitutively literary production of ignorance as a particular kind of historical formation. But it is at the same time concerned with a thematics of ignorance, a thematics that has various dimensions. In this book I explore literary ignorance as having to do with the question of what ignorance feels like, with what it is like to be ignorant. Literary ignorance, for the purposes of this book, involves the question of the ignorance of children or, more precisely, the inability of adults to make themselves understood to children, those beings that they once were, and the fascination that they (adults) have with the ignorance of children. It is concerned with the (philosophical or sceptical) question of other minds and with ways in which the nineteenth-century realist novel in particular might help us to engage with, if not exactly understand, the blank opacities of those other minds, those other people, and indeed therefore to grasp the not-knowing by which the subject is inaugurated. And I am concerned finally with the question of ignorance as a political and moral failing, linked even to the violent abnegation that is articulated or enacted in certain forms of twentieth-century terrorism, but also and at the same time with ignorance as a necessary ethical and political ideal, as that which we need to know, even if we do not (cannot) know it, and with the acknowledgement of epistemological fallibility our own and that of others as the foundation of the ethical, and constitutive even of democracy, of justice, as well as, therefore, of what one might call the politics of poetry.

In addition to these questions, there are various other aspects of the vast, ungovernable and seemingly infinite topic of human ignorance that the book can do little more than touch on or allude to. These include literary representations of the ignorance involved in communities rejecting or denying certain modes of moral or political knowledge, knowledge of the holocaust, for example, or of ethnic cleansing; the (Yeatsian or Foucauldian) question of the relationship between power and knowledge (Did she put on his knowledge with his power/Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?, asks Yeats, famously, of Leda), and the ways in which political and cultural elites are, anthropologically speaking, defined by their control of the dissemination of what is said to be known or what is said to be possible to know, as well as by their claims to superior or special forms of (religious, political, scientific and other) knowing.

Ignorance is, of course, intrinsic to knowledge: in a non-trivial sense, it is through ignorance that knowledge comes about. In order to learn, one has to understand ones ignorance, to know the limits of ones knowledge. And ignorance is growing, exponentially, as they say, with the extraordinary increase in what is known or understood or what is thought to be known or understood, and with the rapidly increasing availability of information, its worldwide dissemination (through the industrialization of printing, of course, but especially with the recent development of the internet and its instantaneous resources, its instant information).