In the Shadows of Glories Past

The title of this volume implies two things: the greatness of the scientific tradition that Muslims had lost, and the power of the West, in whose threatening shadow reformers now labored to modernize in order to defend themselves against those very powers they were taking as models. Copernicus and Darwin were the names that dominated the debate on science, whose arguments and rebuttals were published mainly in the religious and secular journals in Cairo and Beirut from the 1870s. Analysis and interpretation of this literature shows the hope that Arab reformers had of duplicating the Japanese success, followed by the despair when success was denied.

A cultural malaise festered from generations of despair, defeat and foreign occupation, and this feeling transmogrified after 1967 to a psychosis in a significant number of secular writers, educators and religious reformers. The great debate on assimilating science was turned inward where defensive mechanisms of denial spun out perversions of science: the Quran becoming a thesaurus of science; and a more extreme derivative of that, something called Islamic Science, arising as an alternate science that was to be in harmony with the Quran, Sharia and Muslim belief.

This volume reveals the undermining effect of European imperialism on western-oriented religious reformers and secular intellectuals, for whom science and political reform went together, and concludes with a chapter on the state of science in contemporary Muslim societies and the efforts to institutionalize science (before the upheavals of 2011) so as to bring to life an authentic and indigenous culture that would sustain scientific study and research as autonomous pursuits.

John W. Livingston is Associate Professor of History at the William Paterson University of New Jersey, USA.

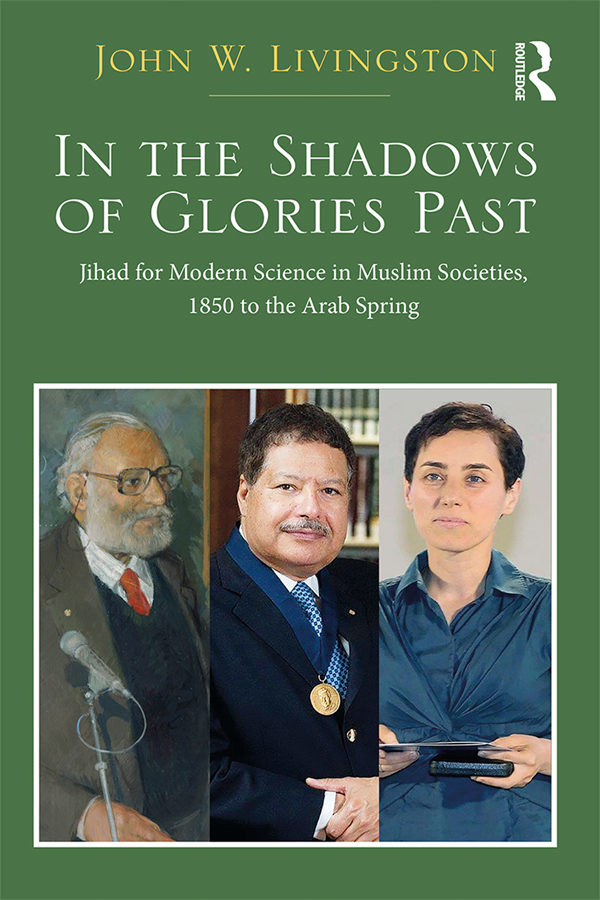

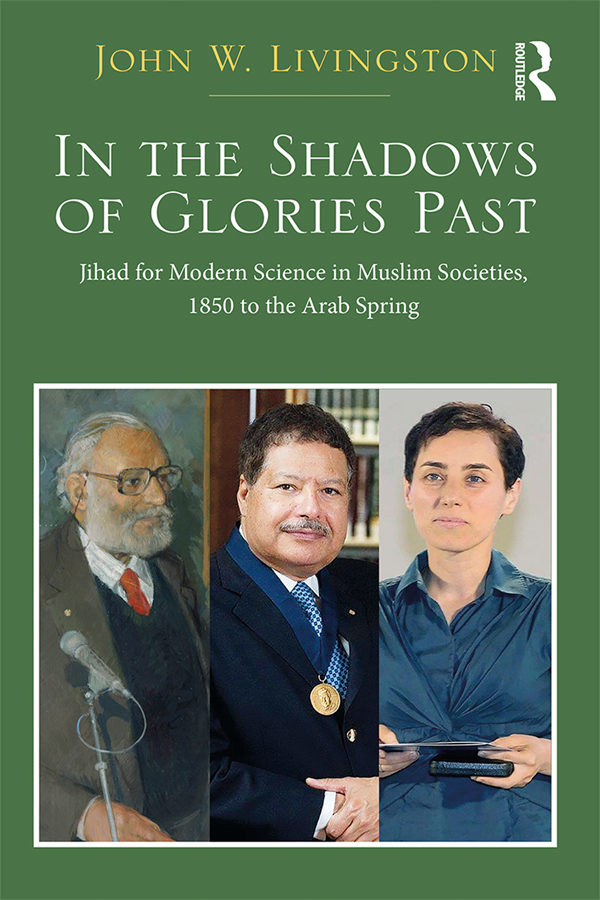

Cover images: Muhammad Abdus Salam (left side of the 3 images), Pakistani, Nobel Prize winner, 1979, in particle physics; died 1996. Image from the portrait collection of St. Johns College, Cambridge University, UK. Ahmed Zewail (middle image), Egyptian, Nobel winner, 1999, in chemistry; died 2016. Image from the portrait collection of the American Chemical Society, Philadelphia. Maryam Mirkhani, Iranian (right image), Fields Medal winner in pure mathematics, 2014; died 2017.

In the Shadows of Glories Past

Jihad for Modern Science in Muslim Societies, 1850 to the Arab Spring

John W. Livingston

First published 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 John W. Livingston

The right of John W. Livingston to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Livingston, John W. (John William), 1932author.

Title: In the shadows of glories past : jihad for modern science in Muslim societies, 1850 to the Arab Spring / John W. Livingston.

Description: New York : Routledge, 2017. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019730 | ISBN 9781472447340 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781315101491 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Islamic modernism. | Islamic renewal. | ScienceIslamic countriesHistory. | Islam and scienceHistory.

Classification: LCC BP166.14.M63 L58 2017 | DDC 297.2/65dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019730

ISBN: 978-1-4724-4734-0 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-10149-1 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

I dedicate this book to my long deceased professor and friend, Martin Dickson. Martin was a professor of Persian language and Iranian history, specializing in the Safavid period and Islamic mysticism, at Princeton University, from 1958 to 1991, the year of his death. He was a mentor and inspiration in learning and life, to me and to many other of his students and those who were fortunate enough to become his friend. His memory lives on, carried by his former students who now teach in universities across the country. Like the mystical poets he studied, and emulated, Martin had a knack of turning the prism to see the universe revealed in unexpected lights. It was my good fortune, my best fortune I should say, to have had him as a friend. With him always in mind, I wrote this book.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Part I

Copernicus, Darwin and Islamic intellectual reform in Muslim societies during the last half of the 19th century

Part II

Science, society and government in the modern Muslim world

In addition to Martin Dickson, to whom this book is dedicated, I would like to thank William Paterson University for two decades of financial assistance in my research for this book; and also the library, whose interlibrary loan librarians were able to locate and provide me with hard-to-find, centuries-old books in Arabic and Ottoman Turkish.

I should also like to thank the American Philosophical Society for a research grant I was awarded, which helped cover expenses for a year in the National Library of Egypt and the library of the American University at Cairo. I also wish to thank Dr. John McClain, formerly in the Department of Physics at the American University of Beirut, who meticulously went over every sentence I wrote, correcting grammar, punctuation, word choice and errors in the science. Professor George Robb of the History Department of William Paterson University is as well to be thanked for the time and effort he graciously put into reading the book and giving critical and insightful recommendations in organization and in deleting what could be deleted and what could be written in shorter form.

Lastly, I would like to thank Melissa Williams for her uncanny ability to put into type a most messy, illegible, hand-written copy covered with crossed-out lines, a dozen arrows stretching across the scrawl-crowded page indicating where to insert a wild artistry of words within bubbles that might have won a prize in a Jackson Pollack imitation contest. How she did it is a mystery, and I am forever indebted to her for it.

Before Sultan Mahmud IIs long, eventful and traumatic reign, an elite circle of ministers and reformers were convinced that in order to survive, the empire had to change drastically by adopting innovations from the West. By the end of his reign, the circle of reformist believers had widened to embrace a large section of literate society. That something had to be done and done quickly, and that the West had the answers, was no longer whispered by a few at the head of government who were living in perpetual fear of accusations by conservatives of treason and heresy one moment and Western demands, threats and ultimatums the next. Europe was not the only threat. The dire weakness of the empire, having suffered the humiliating loss of Greece, and then defeat and loss of Syria at the hands of the governor in Egypt, had made what had been unthinkable during the century following the Tulip Period very thinkable and acceptable, even inevitable, and so between the late 1830s and mid-century, the West as a model to be followed had become generally accepted. Once the Janissaries had been crushed, respected members of the high ulema emerged from the veil of fear to publicly advocate innovative change and an active pursuit of reason in human affairs and social organization, rather than passively relying on Gods will. Fatalism, they now agreed, had been disastrous for both religion and empire.

![Blackford - Freedom of religion [and] the secular state](/uploads/posts/book/167779/thumbs/blackford-freedom-of-religion-and-the-secular.jpg)