Editor: Sasha Lilley

Spectre is a series of penetrating and indispensable works of, and about, radical political economy. Spectre lays bare the dark underbelly of politics and economics, publishing outstanding and contrarian perspectives on the maelstrom of capitaland emancipatory alternativesin crisis. The companion Spectre Classics imprint unearths essential works of radical history, political economy, theory and practice, to illuminate the present with brilliant, yet unjustly neglected, ideas from the past.

Spectre

Greg Albo, Sam Gindin, and Leo Panitch, In and Out of Crisis: The Global Financial Meltdown and Left Alternatives

David McNally, Global Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance

Sasha Lilley, Capital and Its Discontents: Conversations with Radical Thinkers in a Time of Tumult

Sasha Lilley, David McNally, Eddie Yuen, and James Davis, Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth

Peter Linebaugh, Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance

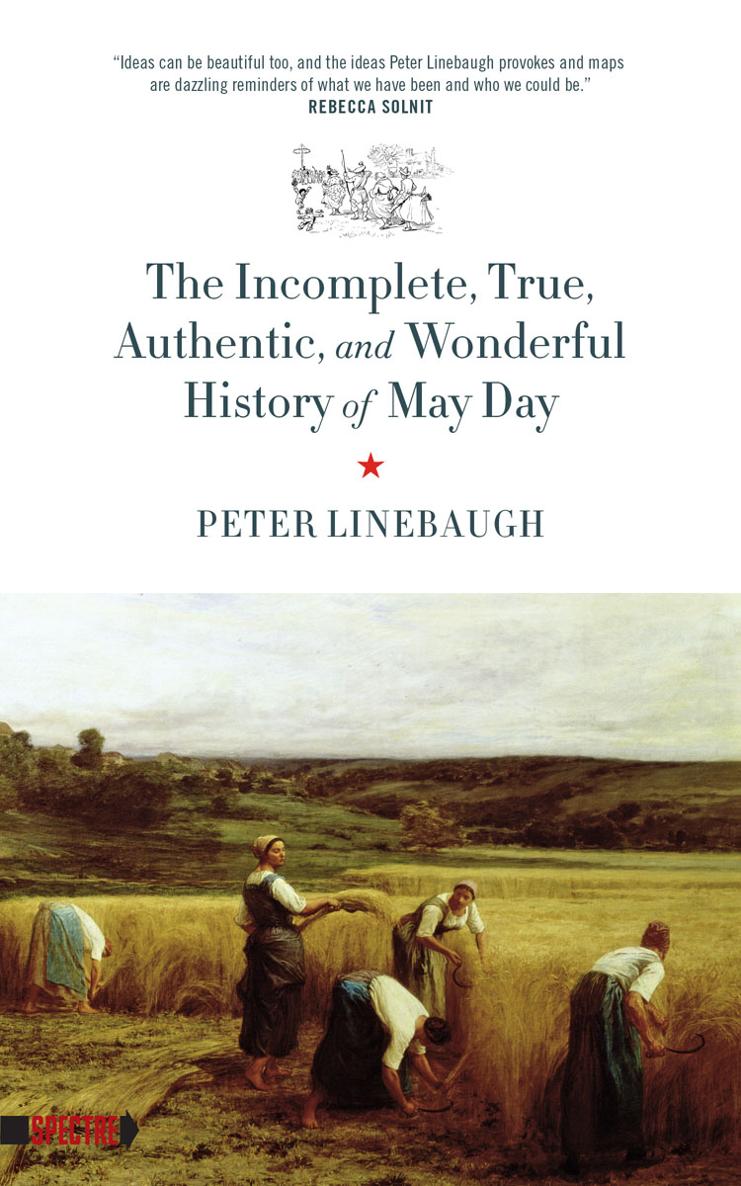

Peter Linebaugh, The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day

Spectre Classics

E.P. Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary

Victor Serge, Men in Prison

Victor Serge, Birth of Our Power

To Robin D.G. Kelley

The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day

Peter Linebaugh

2016 Peter Linebaugh

This edition 2016 PM Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 9781629631073

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015930909

Cover by John Yates / www.stealworks.com

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

ONE | The May Day Punch That Wasnt |

TWO | The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day |

THREE | X2: May Day in Light of Waco and LA |

FOUR | A May Day Meditation |

FIVE | May Day at Kut and Kienthal |

SIX | Magna Carta and May Day |

SEVEN | May Day with Heart |

EIGHT | Obama May Day |

NINE | Archiving with MayDay Rooms |

TEN | Ypsilanti Vampire May Day |

ELEVEN | Swan Honk May Day |

INDEX |

ONE

The May Day Punch That Wasnt

Introduction and Acknowledgements

(2015)

Freight Train sprang up from the crowded picnic bench. Sputtering and dumbstruck he stared the professor in the eye, then leaned across the table ready to throw a punch. Our May Day discussion came to an abrupt conclusion.

Freight Train was over six feet in height and 220 pounds in weight. Professor Elwitt, his senior by two or three decades, was a diminutive and unathletic man. As a possible fistfight it was a mismatch.

They didnt die for me, the professor had said, his lips curling in malice. It was a well-targeted provocation.

Freight Train had just concluded his discourse to the comrades by saying, they died for us. He was being courteous, restrained in his choice of words, but nevertheless direct and to the point. He recited the names of the martyrs, the leaders of the struggle for the eight-hour day. He told of those who fell to the hysterical violence that the government let loose upon the anarchists of Chicago. He spoke of the call for a general strike on May Day 1886, of the meeting on Haymarket Square a few days later when a stick of dynamite was thrown and a cop killed, of the trial of eight anarchists, of the hanging on Black Friday, November 11, 1887, when four were hangedAlbert Parsons, George Engel, Adolf Fischer, and August Spies. These were the Haymarket martyrs, los mrtires, who died for us, as Freight Train said.

We affectionately nicknamed Robert Harmon, the Chicago grad student, Freight Train, because once he got going you couldnt stop him. He loved the IWW and liked to cast himself in a role familiar to young radicals, the last of the Wobblies. He had deep loyalties to the Italian American community of Cicero, Illinois, and hed explain how a combination of the Catholic Church and gangsterism during the 1920s extinguished the hot flame of Italian anarchism. Freight Trains personal mission was to keep that flame alight.

He loved Renaissance history and affected a nonchalance called sprezzatura, described in Castigliones Book of the Courtier (1528). Elwitt had been on his PhD oral examination. Freight Train wanted to explain the birthing stool. So he nonchalantly slid off his chair, spread his arms and legs out wide, starfish style, and from a position nearly on the floor, the heels of his shoes grasping the edge of the examining table and supporting his weight, he illustrated to the astonished examiners the posture of parturition as he imagined it to have been during the Italian Renaissance. This was the way, he explained, that Machiavelli, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the rest came into the world.

At the examining table and the picnic table alike Freight Train could make history come alive.

In the dimming of the day and the onset of evening, Professor Elwitt, the Marxist, made his way over to the table where we were listening to Freight Train. The professor was a socialist, the student was an anarchist, and they each claimed May Day. Elwitt offered fighting words. At a temporary loss for words himself, the anarchist could only act, and he lunged. It was the Red versus the Black.

A storm in a teacup? Or a near-ritual moment, like a wedding or a funeral, worthy of Garca Lorca? It was something of both. There was much to it of the academic spat, worthy of a novel of manners, except that to the participants much more was at stake, the weight of history. Or you could see it in another way: it being springtime there were sexual and generational as well as political energies coursing wildly about, not to mention Dionysus with his overflowing cups. The green budding force of winters end combined with political antagonism of at least a century or two, and the tension was ready to burst. Testosterone bubbled madly in that witchs brew.

Maybe it was the Red and the Green?

We celebrated May Day under a picnic shelter we had rented for the day in the ample and peaceful Ellison Park, Rochester, NY. It was a strictly bring-your-own, potluck affair. We played Capture the Flag across the meadow. Someone with a guitar led us in singing those old labor ballads and civil rights hymns. Beer and wine flowed easily. It was generally laid back, chill. Everyone was usually happy enough. Among the students and workers was the dyer and designer Bethia Waterman, the artist and athlete Joe Hendrick, the brakeman Disco, and arriving on the back of a motorcycle driven by a lesbian physician, the fierce public health advocate, Michaela Brennan, with whom I was to fall in love. We professors had to put aside our theories and abstractions to speak in a way that even children could understand, so another year we organized a skit for them (as theatre it could hardly be called a play). That was the seed that grew into