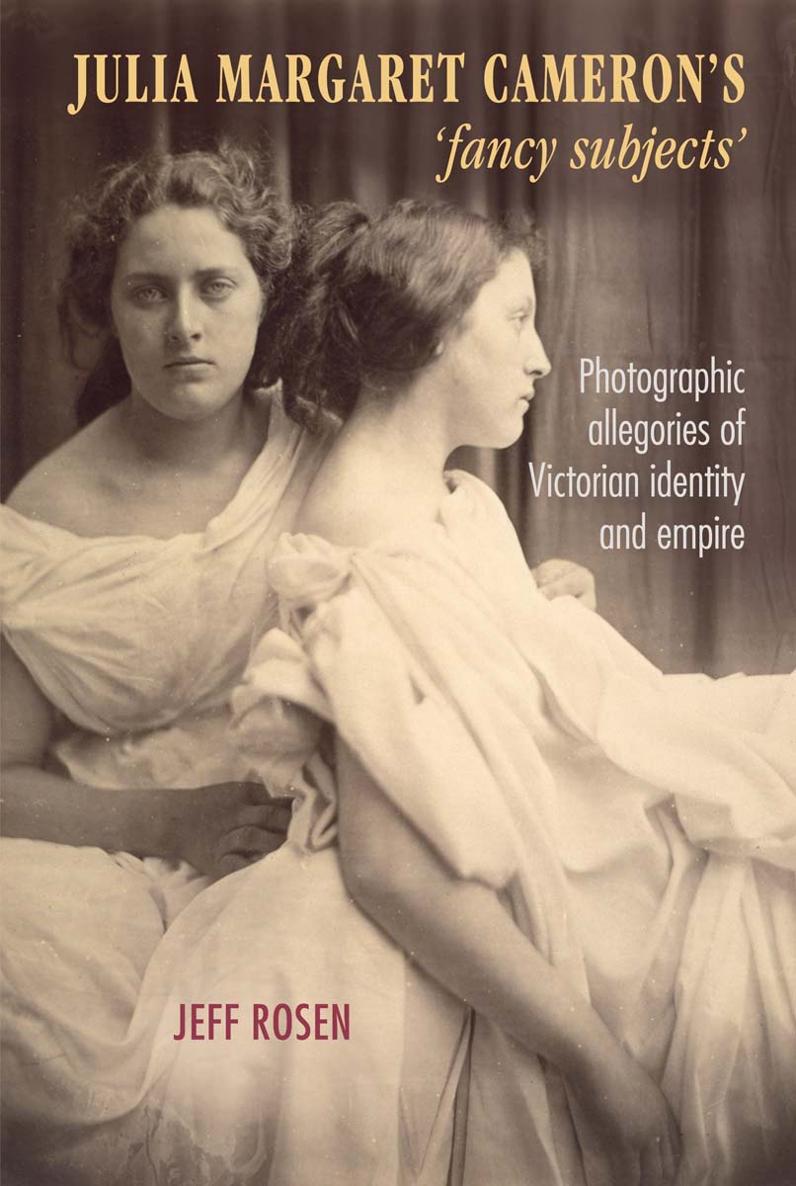

Julia Margaret Camerons fancy subjects

Julia Margaret Camerons fancy subjects

Photographic allegories of

Victorian identity and empire

JEFF ROSEN

Manchester University Press

Copyright Jeff Rosen 2016

The right of Jeff Rosen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 1 7849 9317 7

First published 2016

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset in Monotype Dante by

Koinonia, Manchester

For Lynn

Contents

In the spring of 1985, I took a break from my research in the French national archives and joined my dissertation advisors Susan Siegfried and Rick Brettell at the Centre National de la Photographie to view an extraordinary photography exhibition, Mike Weavers seminal retrospective, Julia Margaret Cameron 18151879. Im grateful to Rick and Susan for introducing me to the possibilities of studying Camerons work and would also like to thank David Van Zanten, Larry Silver, and Holly Clayson for their support during those years. For memorable conversations about allegory, symbolism, and Victorian photography, I would also like to thank Leonard Barkan, Joel Snyder, Anne McCauley, Julie Codell, Debra Mancoff, George Dimock, and Jerry Mead.

Many curators opened their collections to me, and I would like to acknowledge: David Travis and Sylvia Wolf, formerly of the Art Institute of Chicago; David Wooters, Rachel Stuhlman, and the late Robert Sobieszek of the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House; Maria Morris Hambourg of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Weston Naef and Gordon Baldwin of the J. Paul Getty Museum; Roy Flukinger and Linda Briscoe of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin; Pam Roberts of the Royal Photographic Society, Bath; and Mark Haworth-Booth, formerly of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Research leave, fellowship support, and travel grants came from numerous sources for which I am extremely grateful. I would like to acknowledge the Samuel Kress Foundation, the Art Institute of Chicago Old Masters Society, and the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts of the National Gallery of Art, which made my early research possible. I am also grateful for a sabbatical leave and several professional development grants from Columbia College Chicago; a Fanny Knapp Allen Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the University of Rochester; several grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities Travel to Collections program; and a Fleur Cowles Fellowship from the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

to the North American Conference on British Studies. I am grateful for the feedback of friends and colleagues who shared their thoughts after these presentations, and indebted to earlier published studies of Cameron by Julian Cox and Colin Ford, Mike Weaver, Joanne Lukitsh, Victoria Olsen, and Amanda Hopkinson. All opinions, and any errors contained in this book are of course my own.

Almost thirty years ago, after viewing Camerons photography on the Trocadro, Rick, Susan, and I went to a nearby oyster bar to talk about the exhibition. They might not remember the darkness of that night or the chill in the air, but I still do.

Like many artists before her, Julia Margaret Cameron used evocative titles to identify the subjects of her imagery. But sometimes these references are obscure and she left many photographs untitled. Julia Margaret Camerons fancy subjects examines Camerons pictorial allegories, and the titles that she assigned to her photographs help identify each subject. But precise identification can be complicated because she frequently used the same title for different prints, or gave multiple titles to the same image, or returned years later to some photographs to reprint and retitle them yet again.

For example, she titled several photographs Sappho to refer to the ancient Greek poet. She registered one Sappho for copyright on 19 May 1865; she registered another Sappho, using the same model but in a different composition, on 11 November 1865; and she registered a third image on 18 June 1866, using a different model but containing the traditional iconography used to represent Sappho.

To clarify the pictorial references in the text, this book draws upon the catalogue raisonn of Camerons photographs produced in 2003 by the J. Paul Getty Museum and edited by Julian Cox and Colin Ford. The catalogue raisonn contains a reproduction of every photograph produced by the artist. The digital edition of this publication is available electronically to all from the Getty Publications Virtual Library; the permanent URL is: http://d2aohiyo3d3idm.cloudfront.net/publications/virtuallibrary/0892366818.pdf. Accordingly, references to Camerons photographs within this book follow the citation style (Cox no.) to refer readers to the catalogue raisonn number in this publication. In this particular example, the Sappho registered on 19 May 1865 is (Cox 252); the Sappho registered on 11 November 1865 is (Cox 253); and the photograph registered on 18 June 1866 that depicts a woman in an ancient Greek head dress, representing Sappho, is (Cox 340).

Mrs Cameron is making endless Madonnas and May Queens and Foolish Virgins and Wise Virgins and I know not what besides. It is really wonderful how she puts her spirit into people. (Letter from Emily Tennyson to Edward Lear, 1865)

Fancy subjects

When Julia Margaret Cameron took up photography in 1864, she passionately embraced allegory as her preferred artistic impulse and arranged her sitters in poses taken from classical literature, the Bible, contemporary poetry, and recent history. She called these photographs her fancy subjects, borrowing the term from the tradition of academic painting practised by her friend and mentor, George Frederic Watts. Working methodically, she carefully noted the textual sources that inspired her most valued pictures and gave evocative titles to each photograph she produced for public exhibition, mass production, or inclusion in a photographic album. Camerons avid pursuit of photography apparently won her much esteem from friends and neighbours, but her seemingly arbitrary choice of subjects bewildered even some of her most fervent admirers. Emily Tennyson, for example, was clearly confused by the wellspring of her friends imagination and the purpose of her activities.

This book argues that an organizing principle informed Camerons choice of fancy subjects and that they were not chosen randomly or without design. During a decade of activity that started in the mid-1860s, when the medium itself was still young, Cameron created allegories in photography as part of a sustained effort to represent the countrys national heritage and cultural identity. To nineteenth-century Britain, this was a complex inheritance that traced its National Church to ancient Rome and its parliamentary government to ancient Greece. It based its moral guideposts on the heroic legends and chivalric code of medieval England and established domestic norms upon the familial bonds celebrated in biblical tales. It justified its territorial expansion across the globe as part of a civilizing mission that would spread these very ideas and narratives to new lands and peoples in the