Copyright 2014 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10987654321

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-4587-5

A Note on Money

In the late twelfth century Alfonso VIII of Castile issued the gold morabetino or maraved in imitation of Almoravid gold coinage. By the fourteenth century the maraved was a money of account. Thereafter the principal gold coin was the dobla, or double maraved, known as dobla de la banda under Juan II, castellano under Enrique IV, and excelente under Fernando and Isabel. Their respective values were 335 maravedes, 435 maravedes, and 870 maravedes. The standard silver coin was the real valued at 30 maravedes. Gold coins imitating the Venetian ducat and the Florentine florin also circulated. Many everyday transactions involved velln (copper-silver alloy) coins known as blancas, usually two or three to a maraved. For further detail, see Miguel ngel Ladero Quesada, La hacienda real de Castilla, 13601504 (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 2009), and Angus MacKay, Money, Prices and Politics in Fifteenth-Century Castile (London: Royal Historical Society, 1981).

Introduction

Castile and the Emirate of Granada

Ever since the Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century, the Christians had fought to expel them. The present volume describes the ebb and flow of that conflict, known as the reconquest, from the middle of the fourteenth century until its completion in 1492. Accorded crusading status by the papacy, the struggle continued long after serious attempts to recover the Holy Land had been abandoned, and so can rightly be called the last crusade in the West.

The Reconquest: From Abeyance to Completion

Not long after the Muslims destroyed the Visigothic kingdom, independent Christians in the northernmost reaches of the peninsula expressed their hope of recovering the land that had been lost. The idea that the kings of Castile-Len, as heirs of the Visigoths, ought to reconstitute the Visigothic realm, including the ancient Roman province of Mauritania in North Africa, gained early currency and persisted until the close of the Middle Ages. The achievement of that lofty goal was slow, but in the late eleventh century the balance of power shifted in favor of the Christians who drove the frontier south of Toledo on the Tagus River. Invaders from Morocco, first the Almoravids and then the Almohads, temporarily halted that advance but failed to regain lost territory.

Acknowledging that the war against the Moors (as the Christians called the Muslims) was in the interest of Christendom, successive popes offered participants the crusading indulgence or remission of sins, and various personal and proprietary legal protections. The papacy also provided financial aid from ecclesiastical income. As Portugal and Aragn reached their fullest extent by the mid-thirteenth century, only Castile, after conquering Crdoba

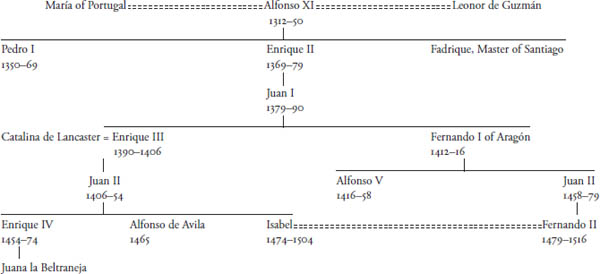

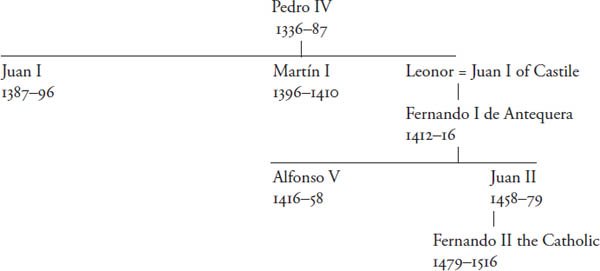

Marinid decline isolated the Narids, but, as they posed no significant threat, the Castilians felt no urgency to attack them. Consequently, the reconquest fell into abeyance. No longer troubled by a possible Moroccan intrusion, Pedro I concentrated on war with Aragn and the opposition of his half-brother, Enrique of Trastmara, but never undertook a sustained campaign against Granada. The Trastmara monarchs, concerned to secure their throne, arranged a series of truces with the Narids extending into the early fifteenth century. The rupture of the truce enabled Infante Fernando, as regent for Juan II, to capture Antequera in 1410, but his election as king of Aragn diverted his attention from Granada. Quarrels with the nobility disturbed the long reign of Juan II, who defeated the Narids at La Higueruela in 1431 but failed to gain any territory. His son Enrique IV ravaged Granada early in his reign, but increasing discord with the nobility and a dispute over the succession thwarted his efforts to subjugate the emirate. These intermittent crusading efforts are essential to a full understanding of the Castilian conquest of Granada and ought not to be passed over lightly.

After so many years of sporadic military operations, Fernando and Isabel, the Reyes Catlicos or Catholic Kings, made the conquest their chief priority. After bringing the fractious nobility to heel, they provided an outlet for their aggressiveness in the war against the Moors. With public order and the prestige of the monarchy restored, they marshaled the resources of the realm and of the church to support the war. Despite the expense and the exhaustion of their people, the king and queen, armed with crusading bulls, persisted in their task for ten years, using artillery to reduce one stronghold after another. Following the capitulation of Granada in 1491, they entered the city in triumph in January 1492. The reconquest was over. As a political entity Islamic Spain was no more. However, the incorporation of thousands of Muslims into the Crown of Castile proved to be a most arduous task.

Granada Around 1350

Mountain ranges intersected by valleys and plains dominated Narid Granada and impeded the conquest. Dotting the landscape were walled cities, each with its citadel (alcazaba) and a string of dependent castles controlling the surrounding region. Countless watchtowers provided early warning of enemy movements in the contested no-mans land between Castile and Granada.

The Mediterranean Sea defined Granadas southernmost boundary. East of Gibraltar the ports of Estepona, Marbella, Fuengirola, Mlaga, Vlez Mlaga, Almecar, Salobrea, Adra, and Almera marked the coastline until it turned northward to Vera and Aguilas adjacent to Castilian Murcia. North of Gibraltar Castellar, Jimena, and Arcos de la Frontera established the western Castilian border before shifting eastward to Olvera. Opposite that line was Ubrique on the edge of the Sierra de Grazalema. Ronda, adjoining the Serrana de Ronda, was the most important Muslim fortress in the west. Between there and Mlaga were lora and Con. The deep valleys and inaccessible terrain of al-Sharqiyya (Ajarqua) provided a strong defensive bulwark for Vlez Mlaga and Mlaga. On its northern edge was Alhama. From Olvera the northern frontier ran eastward through Antequera, Archidona, and Loja and then extended just north of the capital.