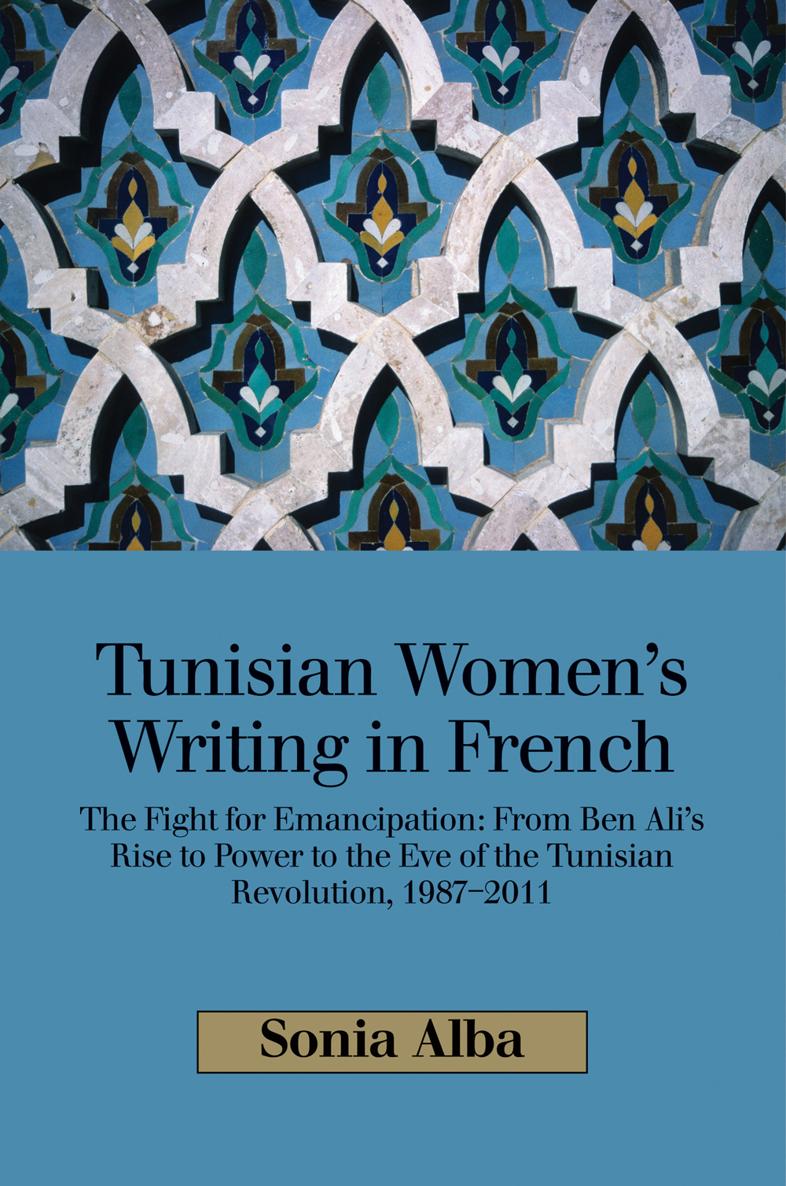

Tunisian Womens

Writing in French

I dedicate this book to my parents

Christine and Santo,

and to my sister

Sandra.

Thank you for your love, caring and continuous support.

Tunisian Womens

Writing in French

The Fight for Emancipation: From Ben Alis Rise to Power to the Eve of the Tunisian Revolution, 19872011

Sonia Alba

Copyright Sonia Alba, 2019.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2019

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139, Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

Distributed worldwide by

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 N. Franklin Street

Chicago, IL 60610, USA

ISBN 9781845199395 (Hardcover)

ISBN 9781782846055 (EPub)

ISBN 9781782846062 (Kindle)

ISBN 9781782845577 (Pdf)

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

Contents

Acknowledgements

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the following for permission to reproduce copyright material. Every attempt has been made to identify the copyright owners for these works and to obtain permission to publish them. The publishers apologise for any errors or omissions in the list below and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in the next edition or reprint of this book.

Bji, Hl. Une force qui demeure. Paris: Arla, 2006.

Ben Mhenni, Lina. A Tunisian Girl. Blog.

http://atunisiangirl.blogspot.co.uk/ 2009 present.

Bessis, Sophie. Les Arabes, les femmes, la libert. Paris: Albin Michel, 2007.

Chamkhi, Sonia. Lela ou la femme de laube. Tunis: Elyzad, 2008.

Zouari, Fawzia. La Retourne. Paris: Ramsay, 2002.

Sonia Alba would also like to thank the following for their permission to reproduce material from their interviews with her: Hl Bji, Lina Ben Menni, Sophie Bessis, Sonia Chamkhi and Fawzia Zouari.

Introduction

Understanding Tunisian

Francophone Womens Writing

A strong tradition of writing in French exists in the Maghrebi countries of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. As Abdelkader Cheref claims, however, it is in Algeria that Maghrebi literature in French has developed the most, thanks to the work of prominent writers such as Kateb Yacine, Rachid Mimouni, Assia Djebar and Mohammed Dib (35). Cheref explains the greater production of literature in French in Algeria as a result of the stronger link that Algeria has had with France compared with Morocco and Tunisia. According to Cheref:

It is in Algeria, much more so than in Morocco or in Tunisia, that Maghrebi literature of French expression is profuse. It is because French occupation lasted longer, schooling in French language started earlier and the impact of French culture on the autochthonous outlook was particularly significant. (35)

Despite this, a rich vein of literature in French also exists in Tunisia and has, over the years, attracted the interest of a number of academics.

The book is structured around three chapters, each dealing with a different form of literary expression: the autobiographical novel and the novel, the politically engaged essay and the blog. The deliberate decision to focus on such varied forms of writing contributes to differentiating this book from other studies which have not combined a focus on three such genres within a single study. Such a choice, it must be noted, challenges notions of high culture and mass culture and merits further discussion. As Stuart Hall claims in his seminal Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (1997), culture is one of the most difficult concepts in the human and social sciences and there are many different ways of defining it (2). In the attempt to define culture, a distinction is often made between those classic works of literature, painting, music and philosophy commonly understood as high culture and more modern, popular artistic productions, often referred to as mass culture, which includes popular music, publishing, art, design and literature, or the activities of leisure-time and entertainment, which make up the everyday lives of the majority of ordinary people (Hall 2). The distinction between high culture and mass culture often carries a powerfully evaluative charge, Hall claims (2). Whereas novels and essays may be classified as high culture and blogs as mass culture, by applying the same analytical tools to the analysis of the selected texts, an attempt is made to challenge this distinction, valuing equally the contribution of each writer within Tunisias cultural panorama. This is not to say that the question of audience has not been considered; indeed, if it is true that members of different social classes consume different cultural products, an additional strength of the approach adopted relies precisely on including such a variety of texts. By focusing both on essays, which may only be accessible to an educated audience, and on more popular forms of writings such as the blog, the argument presented provides a more inclusive analysis of Tunisias literary production than a study of the essay or the novel alone would provide.

The works by a number of writers will be analysed, specifically Fawzia Zouari, Sonia Chamkhi, Hl Bji, Sophie Bessis, Lina Ben Mhenni and an anonymous blogger known as Nadia (hereafter she will be referred to as Nadia). A brief biography of each writer will be provided in the chapters dealing with the authors work. will analyse Lina Ben Mhennis blog A Tunisian Girl and the blog Nadia from Tunis by Nadia. All of the writers, with the exception of the anonymous blogger, have given interviews for the purpose of this study only. Some of the material collected through these interviews will be included in each chapter.

Generational differences between the selected authors, as well as differences in terms of social class affiliation and economic status are evident and will be discussed throughout. Indeed, Bji and Bessis were born in colonial Tunisia and belong to Tunisias elite. Educated in French under colonial rule, they have witnessed the countrys struggle for decolonisation, Bourguibas instauration as the countrys first president in 1956 and Ben Alis coup in 1987. Bji and Bessis, like fellow Tunisian women writers from the same generation such as Souad Guellouz, Jalila Hafsia, Aicha Chabbi, Leila Ben Maami and Hayet Bencheikh were among the first women writers in Tunisia to gain literary recognition, opening the way for succeeding generations of women writers in Tunisia (Godi-Tkatchouk and Andriot-Saillant 116). By contrast, Zouari and Chamkhi were born on the eve of decolonisation and grew up in the post-colonial state. They share more modest origins compared to Bji and Bessis but both were able, like their older fellow writers, to pursue university studies in France up to Ph.D. level. Finally, Ben Mhenni and Nadia grew up under Ben Alis rule and until the day of the Revolution had known no other political governance than the one led by the toppled dictator. Whereas the analysis of the texts in will thus reveal the distinct challenges faced by young people in Tunisia and the tools they have to mobilise against authoritarian and patriarchal authority. Generational and economic differences, but also religious and national differences between the selected writers (indeed, Bessis is of Jewish origins whilst Bjis is half French), lead to a variation in the authors perceptions of womens rights in Tunisia and first-hand experience of daily life in Tunisia as a woman. Such a variety in experiences and consequent impact on each authors writing, supports this books attempt to provide a broader analysis of Tunisian women writing in French.