2020 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Strange, Jason G., author.

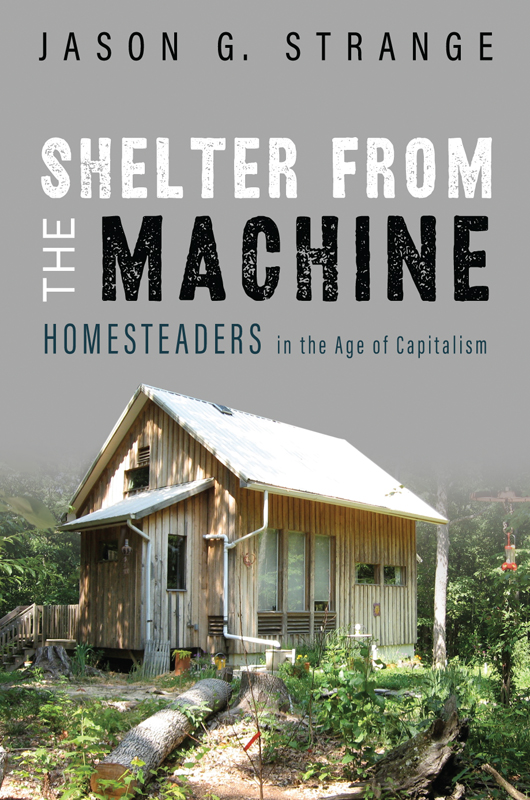

Title: Shelter from the machine : Homesteaders in the age of capitalism / Jason G. Strange.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019032949 (print) | LCCN 2019032950 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252043031 (cloth) | ISBN 9780252084898 (paperback) | ISBN 9780252051890 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Self-reliant livingAppalachian Region, Southern. | Self-reliant livingKentucky. | Frontier and pioneer lifeAppalachian Region, Southern. | Frontier and pioneer lifeKentucky. | Subsistence economyAppalachian Region, Southern. | Subsistence economyKentucky. | Sociology, RuralAppalachian Region, Southern. | Sociology, RuralKentucky. | Appalachian Region, SouthernSocial conditions21st century. | KentuckySocial conditions21st century. | United StatesRural conditions.

Classification: LCC HN 79. A 127 S 77 2020 (print) | LCC HN 79. A 127 (ebook) | DDC 307.7209756/9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032949

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032950

To my parents, who gave the gift of books

Acknowledgments

The one person guaranteed to learn a ton from a book is the one who writes it. Partly thats because of writings unique power to support learning and self-transformationbut its also because the writing process requires so much feedback and support from other people. Acknowledgments abound with heartfelt thanks, and now I know why: it is both humbling and exhilarating when others read your words and suggest ways to make them more accurate, perceptive, and graceful.

Special thanks to those who provided wisdom and guidance the whole way through, or a hand up at crucial moments: James Engelhardt, George Strange, Julya Westfall, Chad Berry, and Dave Zurick. And to those who gifted my drafts with the benefit of their insight and skill: Nancy Sowers, Chris Green, Beth Feagan, Nancy Gift, Broughton Anderson, Mai Nguyen, Michelle Flannery, Amy Harmon, and Kent Gilbert. Steve Fisher and an anonymous reviewer gave the manuscript incredibly generous and helpful reads. The staff at the University of Illinois Press served as gentle, expert guides in a long and complicated process. Finn was an upbeat companion as I wrote and edited, often in different parts of the country in our VW van, and was usually the first to hear a newly finished chapter and offer his dad an encouraging pat on the back.

As the culmination of years of writing and research and thinking and living, this book could not exist without that web of mutual support that makes us humanfriends and family, teachers and mentors. For me, that web includes, in addition to those already named, Debbie Barack, Isaac Bingham, Michael Burawoy, Alice Driver, Patrick and Mary Finn, Alejandro Guarin and Elisabeth Norcliffe, Tim Hensley and Jane Post, Michael Johns, Micah and Zuojay Johnson, Rebecca Lave and Sam DeSollar, Abe and Amanda Lentz, Seth Lunine, Meta Mendel-Reyes, Chris Niedt, Orowi Oliver and Peter Rigden, Jesse and Gina Otterson, Sue Roberts, Jean Perry, Naomi Schulz, Josh Strange, Michael Watts, Althea Webb, Tina West, and Craig Williams. Im sure Im forgetting someone important and dear, but only for a tired moment!

Berea College students in two fieldwork classes conducted and transcribed more than twenty archive-quality interviews with both country and bohemian homesteaders, which form part of the empirical foundation of this work. Thanks and props to Maryam Ahmed, Huda Al-Sammarraie, Lucas Bates, Duncan Blount, Dalton Brennan, Courtney Conyers, Kahndo Dolma, Mirline Duphresne, Jessica Elston, Anna Harrod, Dondlyn Jackson, Lakeya Jackson, Travis Jones, Erika Mamani, Barry Manley, Ruthnie Mathurin, Keyahdah Muhammad, Bradley Niederriter, Kody Noonan, Katrina Owens, Jazzmine Ramey, Darian Shakelford, Josiah Thomas, Shelby Wheeler, and Shawn Williams. Also, a shout-out to Terry Allebaugh for the wonderful series of interviews he conducted in Disputanta, Kentucky, in the 1970s.

Generous funding is crucial for research and scholarship, and I gratefully acknowledge the support of a Graduate Research Fellowship and a Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, both from the National Science Foundation; the University of Californias Labor and Employment Research Fund Dissertation Fellowship; UC Berkeleys Chancellors Dissertation Year Fellowship; and, in so many ways, Berea College.

Last but certainly not least, deep gratitude to all the homesteaders who shared the stories of their fascinating lives. I had the honor and pleasure of trying to capture some of that wealth in wordsbut I didnt create it. This book is truly theirs.

Introduction

Heaven in a Flower

Even though this book is set in eastern Kentucky, I wrote much of it on my familys three acres in a remote part of northern California. Those three acres represent what I call a homesteada piece of land on which people grow food and build a home and otherwise provide for some of their own needsand its beautiful. The Trinity River flows across the foot of the property, clear and cold and swift from the mountains. Bears leave their wide pawprints pressed into the sandy riverbank, beneath ten-foot-high thickets of Himalayan blackberry. Above the rivers edge are fields full of cropssummer squash and heirloom tomatoes, red potatoes and sweet corn. Theres a jungle-patch of brown turkey figs, and pomegranate trees covered in flowers shaped like scarlet ballerinas. There are things I cant grow at home in Kentucky, like apricots and peaches and Asian pears. My nine-year-old nephew wanders the farm like Mowgli, hair down his back, barefoot and shirtless, feeding himself on blueberries and swimming in the river. My mother stocks the pantry with jars of jam, salsa, and canned salmon from the smokehouse. WOOFersyoung people who work on farms in exchange for room and boardtravel from Poland and Chile and Quebec to learn about homesteading.

But there are problems. In one corner, a straw-bale house sits empty and abandoned. The bales were laid too close to the ground, and fungus threaded itself through the walls. Thousands of sweet cherries withered on the branch just as they ripened, victims of a new invasive insect. On shelves in the pantry, dozens of last autumns butternut squashes molder, rat-chewed and wasted. The jars of smoked salmon are almost used up; a couple of years ago, an inexperienced visitor burned down the smokehouse. Yesterday, just as the temperature hit 103, the controller on the irrigation pump shorted out, and the plants droop in the fields. My family works late, scrambling to bring in money to cover the mortgage. Then they get up early, scrambling again to keep the cherries sprayed and the chickens watered and the rats trapped. Their homestead is by no means a failure; its a work of art, a living sculpture. At the same time, its like a broken-winged bird that cant quite get off the ground. Is the labor worth it? Does it make economic sense? Why do they persist?

Questions about homesteading have been with me a long time. When I was nine, my parents bought fifty acres of wooded hills at the end of a gravel road near our hometown of Berea, in Appalachian Kentucky. They dreamed of building their own home, of gardening, of living in peace and beauty outside the system. They werent alone. Together with the neighbors, we raised pigs and split firewood and sawed out lumber. We drove country roads to work parties and pottery firings and Harvest Moon celebrations where back-to-the-landers danced all night beside the bonfire. We played volleyball at potlucks, in pastures balanced on hillsides, where an errant ball would scatter the chickens and send a bare-chested hippie leaping down the mountain in pursuit, braid dancing behind him like a horsetail.