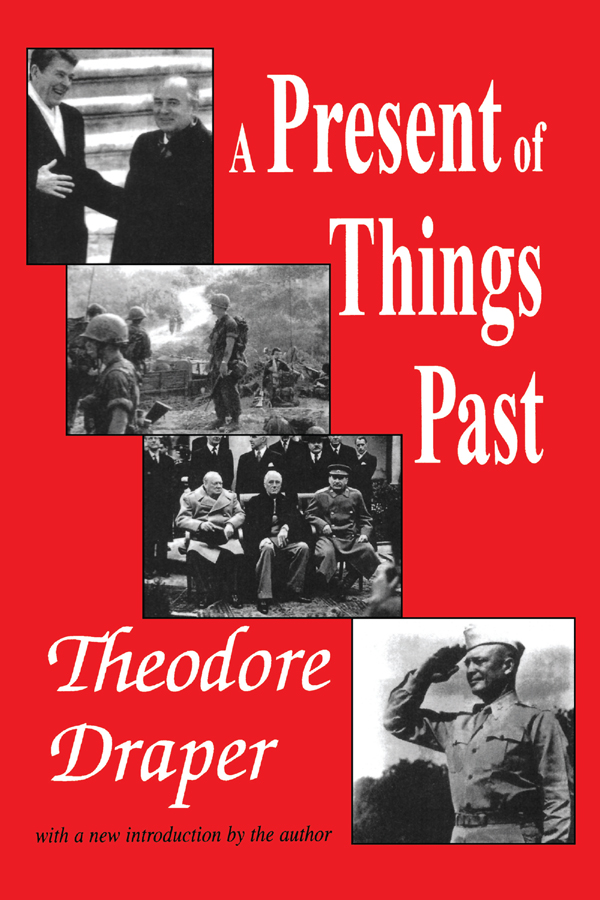

Originally published in 1990 by Harper & Collins.

Published 2002 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2002 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

The author is grateful to the following publications for permission to reprint, in somewhat different form, previously published material: Dissent, The New Republic, The New York Review of Books, and The New York Times.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 00-056796

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Draper, Theodore, 1912-

A present of things past/Theodore Draper.

p.cm.

Originally published: New York: Hill & Wang, c 1990. With new introd.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN: 0-7658-0713-0 (alk. paper)

1. United StatesForeign relations1945-1989. 2. United StatesForeign relationsSoviet Union. 3. Soviet UnionForeign relationsUnited States. 4. CommunismSoviet Union. 5. CommunismUnited States. 6. Soviet UnionForeign relations1945-1991. I. Title.

E840 .D76 2000

909.825dc21 00-056796

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0713-7 (pbk)

IN THIS COLLECTION, the reader will find two essays on American Communism. I wrote them in 1985-1987 in response to a flurry of academic studies of the subject. Now American Communism has attracted new attention as a result of revelations about Communist espionage for the Soviet Union. I have nothing to say about that subject, about which I know no more than I have read, but I do wish to consider an implication which has been drawn from the published material, such as the Venona transcripts.

Broad generalizations have been made that the American Communist Party was an espionage agency for the Soviet Union. This sweeping judgment is rarely based on any intimate acquaintance with the party; it derives from the proven participation of some party members and sympathizers in the Soviet espionage network, mainly in the late 1930s. Yet that period was a peculiarly complex one and needs some explanation

The Popular Front was introduced in 1935 and lasted until 1939. It followed five years of an exceptionally narrow and sectarian policy. It did not originate in the United States; it was the American version of a turn promulgated by the Communist International in 1935, Its principal aim was the Americanization of the American party. The chief slogan was Communism Is Twentieth-Century Americanism. More new members entered the party in this period than ever before. The membership was about 7,000 in 1930, 26,000 in 1934, and 75,000 in 1938.

Yet in the Popular Front years, the most far-reaching purges took place in the Soviet Union. The Old Bolsheviks were condemned in the show trials and liquidated. Stalinism in all its brutality and vindictiveness showed itself at its worst.

I have often been asked why there was so little concern in the American party about the purge-trials in the Soviet Union. There was no considerable exodus or protest. The fates of Zinoviev, Bukharin and many others did not touch most American Communists for whom they were figures from a previous decade.

The basic explanation is that the purge-trials and the Popular Front happened to coincide. The American party seemed to turn away from its obsessive submission to the Soviet Union. The new and old party members were given short-cut lessons in American history. They read about the trials in the Daily Worker, if they read the Daily Worker, and many did not appreciate that what was happening in the Soviet Union was deeply pertinent to their own cause.

I may offer myself as an exhibit. I went to work on the Daily Worker in 1935 as Assistant Foreign Editor. It was en empty title, because there were only two of us on the foreign desk, the foreign editor and myself. I then went on for two years as foreign editor of the weekly New Masses.

In 1935, I was twenty-three years old. I knew nothing about Soviet Russia. I knew that it was the great Communist state which was never to be criticized. But I knew nothing about the history of the American or Russian parties in the preceding fifteen years, and no one cared to bring up the past. This was an apparently new party dedicated to the best interests of the United States, the party of the underdog, the oppressed, the forgotten.

I worked on the Daily Worker and the New Masses while the purges were going on, and yet they meant little to me. My education had not given me any notion of what Zinoviev or Bukharin had stood for in the previous decade, and now my Popular Front consciousness was America-oriented, not Russia-oriented. My subject was foreign affairs, but I never wrote anything about what was happening in the Soviet Union. The civil war in Spain touched me far more intensely than anything happening in the Soviet Union.

At no time did anyone suggest to me anything that implied espionage or doing any other kind of work for the Soviet Union. Of course, I was not in a position to do such work, because I was not in Washington and had not even as yet visited Washington. Still, the fact is that the subject of working in behalf of the Soviet Union in any way never came up, and it is hard for me now to imagine how it could have come up in the normal course of events.

Nevertheless, I once narrowly escaped getting drawn into the Soviet orbit. Some time in 1936 or early 1937, I was chosen to go to the Soviet Union as the Daily Worker correspondent. The resident correspondent had been there for several years and had decided that he wanted to come back home. I was told that I was going to replace him, though I had never been outside the country. In any case, I prepared to go, vacated the rented apartment, sold the furniture, was given tickets on a boat to cross the Atlantic, waited for the appointed day. Just before leaving, I was called in by one of the top officials and told that my trip was delayed and that I would have to wait a while. I was next called in and told that the entire project had been called off.

I was stunned. I soon left the Daily Worker for the New Masses. It was my first great blow in the party. I later found out what had happened. Someone had discovered that my brother, Hal, was a Trotskyist. That was enough to end my career as a Daily Worker correspondent in Moscow. In retrospect, this denouement was a blessing. It did not seem so at the time.