The Spanish quinqui film

Delinquency, sound, sensation

Tom Whittaker

Manchester University Press

Copyright Tom Whittaker 2020

The right of Tom Whittaker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN978 1 5261 3177 5hardback

First published 2020

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

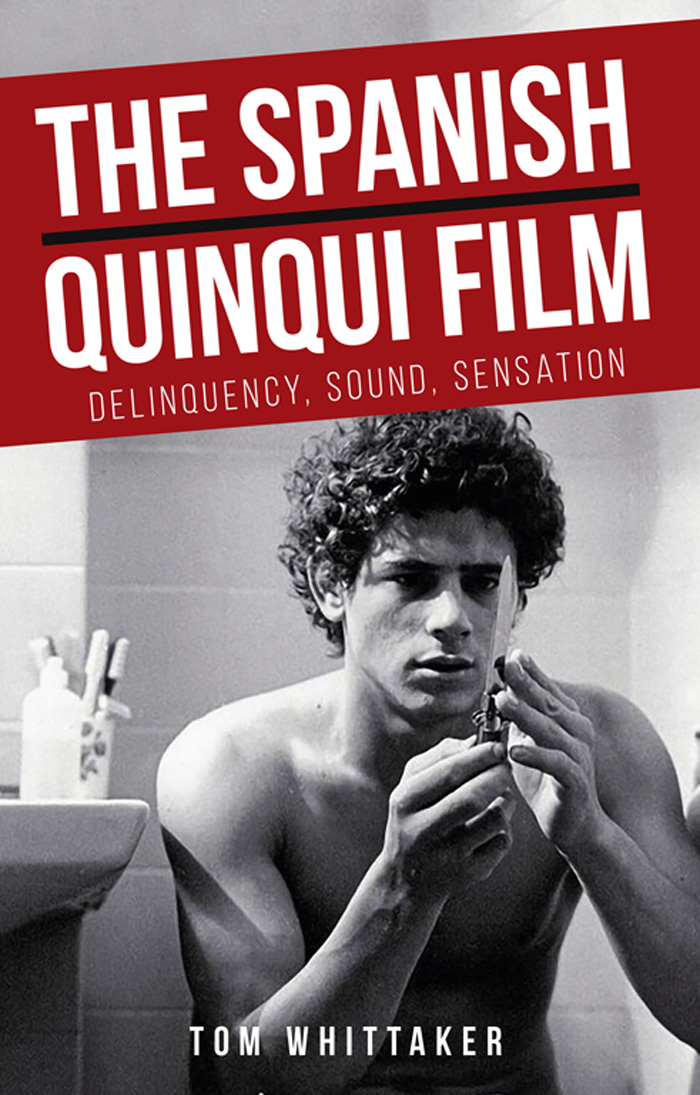

Cover: Press shot featuring Jos Luis Manzano

(image reproduced by permission of EGEDA)

Typeset

by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd

This book would not have been possible without the time and intellectual generosity of others.

My thoughts on cine quinqui, Spanish cinema and sound have been stimulated by many colleagues and friends over the past few years, to name but a few: Dean Allbritton, Ann Davies, Brad Epps, Jo Evans, Sally Faulkner, Julin Daniel Gutirrez-Albilla, Patricia Hart, Jo Labanyi, Antonio Lzaro-Reboll, Samuel Llano, Abigail Loxham, Steven Marsh, Leigh Mercer, Alberto Mira, Jorge Prez, Vicente Rodrguez Ortega, Paul Julian Smith, Jon Snyder, Sarah Wright and Kathleen Vernon. I owe a special thanks to Jamie Hakim, Alejandro Melero, Chris Perriam, Davina Quinlivan, Alison Ribeiro de Menezes, Rosi Song, Sarah Thomas, Nria Triana-Toribio, Duncan Wheeler, Andy Willis and Beln Vidal for reading drafts and chapters of this book at its various stages.

Thanks are also due to the University of Liverpool and the University of Warwick for providing me with periods of study leave to work on this book. The staff at the Reuben Library, BFI Southbank never failed to cheer me up when the writing got tough. I am also grateful to Mery Cuesta for sharing some of her quinqui films with me. I would in addition like to thank the staff at Manchester University Press for their constant support thoughout this project.

, edited by Santiago Fouz-Hernndez. I am very grateful to the editors for their thoughtful suggestions.

Last but not least, I am, as always, grateful to Michael, for his unbounded patience and kindness. This book is dedicated to him.

A stolen SEAT 124 drives at lightning speed past the police, its engine at full throttle as the tyres skid into the curb. The driver is a 15-year-old delinquent who wears skin-tight denim, a flashy medallion and speaks in slang. He negotiates a hostile physical environment of hastily built tower blocks and squalid reformatories with an almost magical ease of movement. Devoted to instant gratification and the sensuous pleasures of consumerism, he embodies the imperative of accelerated capitalism yet is also excluded from it. To Spanish audiences, this is an instantly recognisable protagonist of cine quinqui, a term used to describe a number of films made in Spain in the late 1970s to the mid 1980s which focussed on the theme of juvenile delinquency. His deviance is frequently marked out through sound: the guttural grain of his voice; the ambient noises of gunfire, motorbike engines, arcade games and police sirens; and the music of rumbas, songs by popular gypsy groups whose lyrics spoke of police brutality and marginalisation. Living on the margins of the city, the place of the delinquent in cine quinqui is marked by its dislocation, one that is both spatial and sonic. Except for in the cinema, where teenage audiences from the suburbs shout, jeer and break into sudden applause as the delinquent actor outwits the police. The voices of the audience resonate and vibrate through the auditorium, fusing into those of the delinquent on screen.

Juvenile delinquency, uneven development and Spanish film

If the mercheros were originally known for their itinerant movement across the country, the term quinqui came to be associated with juvenile delinquents who were living more specifically in the outer suburbs of major cities.

: 234).

Aside from its belatedness, however, what distinguished the Spanish crime wave from those of other Western countries was its specific coincidence with a tumultuous period of political uncertainty and change.

another, this insecurity was most clearly articulated through a fear of crime and in particular the figure of the juvenile delinquent. As such, juvenile delinquency became a powerful cultural symbol during these years, a potent site of meaning and affect whose political currency was frequently more important than the nature of the crimes actually committed.

Just as juvenile delinquents increasingly populated the pages of Spanish newspapers, their images soon enough found their way onto Spanish screens, with several filmmakers quick to capitalise on the nation's growing preoccupation with youth crime. The Barcelona-based director Jos Antonio de la Loma, in particular, was fascinated by the criminal trajectory of Juan Jos Moreno Cuenca el Vaquilla, who at just 15 years of age had become infamous for escaping from every detention centre in the country. Shot on location in the impoverished barrio of La Mina in Barcelona, de la Loma's film Perros callejeros/Street Warriors (1977) was partially inspired by the events of the delinquent's life. In spite of having no previous experience of acting, Moreno Cuenca was asked to play the protagonist a casting decision that was promptly thwarted by the juvenile courts which prevented him from taking part in the film. As a result, his friend ngel Fernndez Franco el Trompeta subsequently stood in to take the leading role of el Torete instead. Perros callejeros was far from the first film to explore the theme of delinquency in Spanish film. The films Los golfos/The Delinquents (Carlos Saura, 1961), Los chicos/The Young Ones (Marco Ferreri, 1960) and El espontneo/The Rash One (Jorge Grau, 1964), for instance, explored the relationship between delinquency and marginal space in Madrid, while Young Snchez (Mario Camus, 1964) and El ltimo sbado/The Last Saturday (Pedro Bala, 1967) turned their attention to youth in the suburbs of Barcelona. In their formal experimentation and neorealist-inspired aesthetics, however, these films were primarily aimed at art cinema consumption and therefore at a public who were evidently distinct from the kinds of marginal subjects depicted on screen. In contrast, Perros callejeros more specifically targeted the youth demographic, who recognised their clothes in the way the actors dressed and their own slang in the naturalistic way in which the non-professional actors spoke. If the earlier delinquent-themed films maintained an aesthetic distance from the social deprivation exhibited on screen, Perros callejeros fully immersed audiences within it. In its sensuous evocation of movement and thrills, the film established a close and visceral connection with its audiences, one that signalled a truly popular cinema.