For Sadie Jane and Rory Joseph

The world is so full of a number of things,

Im sure we should all be as happy as kings.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, A CHILDS GARDEN OF VERSES

CONTENTS

Guide

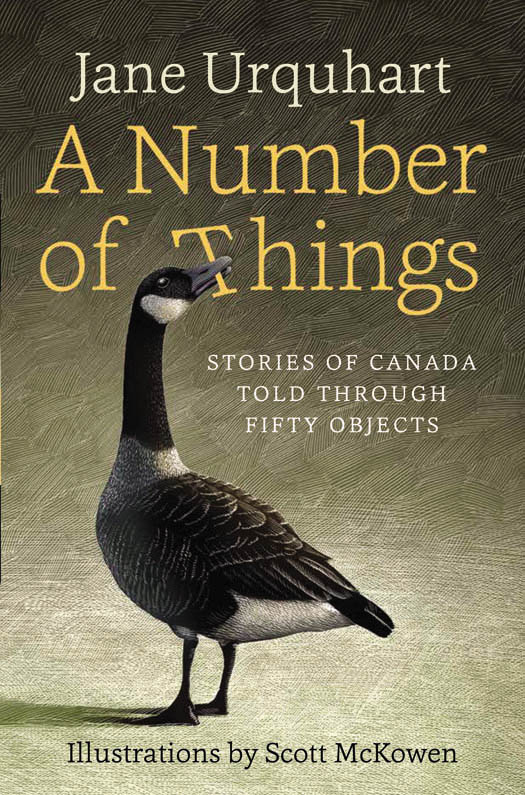

A COUPLE OF YEARS AGO, WHEN PUBLISHER Patrick Crean invited me to mark Canadas 2017 sesquicentennial by writing about fifty objects, my first reaction was one of alarm. Had almost fifty years really passed since the much-celebrated centennial year, with its train whistles shrieking the first four notes of O Canada, its hippies dressed in the new Canadian flag, its oddly shaped poured-concrete architecture, and its symbolic flames and geometric maple leaves? Because if this was so, then it had been half a century since I was an adolescent.

Once I recovered from this shock, however, I became intrigued by the idea of writing about objects. Anyone who knows me can attest to the fact that objects have played a significant role in my life (particularly if you believe, as I do, that works of architecture can be classed in the object category). One could say I have spent a lot of time moving in and out of objects, as well as carting a great number of slightly smaller objects in and out of slightly larger objects. Every single one of the objects in question was and remains important to me, not the least because of the captivating stories associated with them. Some of the objects are of ancestral origin, while others were purchased by me in moments of weakness. But each of them possesses a unique narrative, if only concerning the routes they took to become a part of my life.

But as I was to discover, the history of an object itselfthe how and why it was fashioned; whether it is organic, or mercantile, or spiritual in nature, or a combination of the threeopens up like a fan to reveal a much, much larger picture. It becomes impossible to think deeply about, for example, a beaver hat without investigating attitudes to animal life, colonization, ecology, the fur trade, capitalism, imperialism, the use and misuse of natural resources, and on and on. The same is true of a pine board, a concrete block, or a gas tank. But sometimes the objects in question are more innocent and uplifting: a dance hall, a revered rock face, a simple pair of spectacles, or a medal given to a Canadian for his contribution to world peace.

One of the big questions that arises from the existence of this book (which is itself an object) is why I was chosen to assemble these objects. The answer can only be connected to serendipity. My fiction has sometimes been associated with Canadian history, and long passages of it are concerned with a closely observed world. But I have not spent my life examining every single object in the part of North America known as Canada. Nor do I consider myself to be in a position to make judgments about what should and shouldnt be included in a list of things Canadian. I was asked, and I said yes, and after I said yes, I began to write about phenomena that interested and moved me. Another author would undoubtedly have picked an entirely different set of objects.

The title occurred to me quite early on. The world is so full of a number of things, I thought, remembering the couplet by Robert Louis Stevenson, Im sure we should all be as happy as kings. It wasnt long before I realized that not everything I was writing about was happy in the way that term is most often defined. (Also, to be honest, I am not certain that kings are all that happy.) I liked the poem too much to change it, however, and so, for my own purposes, I opened up the word happy. In my life I have been happiest when I have been engaged with or interested in a person, an art form, a narrative, an object, the unfolding of certain events. I decided to allow the word happy to include a state of fascinationwhether that fascination attached itself to the dark or the light, or to various shades and shadows in between.

The amount I learned about this country, simply by turning my attention to fifty objects one after another, is immeasurableso much so that I would advise readers of this book to research their own fifty objects to see where that quest might lead them in terms of a greater understanding of Canada. That being said, one of the most exciting things I learned was that Canada is always under revision, and probably will remain a work-in-progress for as long as it exists. Canada has never developed an official history, for instance. Nor has it adopted an official cultural standpointor at least not one that stuck. This lack of certainty about identity, once seen as a drawback of being a colony, has allowed for multiple points of view and a greater-than-average amount of adaptability. And it has contributed, in my opinion, to the growth of a nation that is full of a delightful and fascinating number of things, people, cultures, animals, birds, landscapes, arts, books, theatres, sports, politics, religions.

There were surprises as I worked on this book, of courseand plenty of them. One surprise, at least to me, was that while I had believed that Canadaespecially nowwas essentially a secular country, it in fact concerns itself with things of a spiritual nature, in some form or another, on a daily basis. First Nations tribes still focus on the preservation of nature, and know that it is important to show respect for the spirits of the land and the elements. While some of the lovely English-style churches that I connect with my childhood have sagging roofs and dwindling congregations, new examples of religious architecture are appearing in our landscape, thanks to both the reverence and the vitality of some of our more recent immigrants, whose systems of belief are both ancient and permanent. In a less formal way, many of us look quietly inside ourselves for guiding principles, or find ourselves defining quality of life in a way that is not necessarily rooted in enterprise or gain.

There were also large and startling contradictions that revealed themselves as I looked into the history of these objectsundeniable injustices on the one hand, and the existence of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms on the other. Or careless and greedy harvesting of natural resources set against the Canadian peoples love of and respect for wilderness landscapes.

A large portion of this book was created not by me but by the gifted draughtsman and illustrator Scott McKowen. Early in the process I asked Scott if he would consider drawing the objects I had selected, and not only did he agree, but he entered into the project with a more than generous amount of enthusiasm. Much better organized than I, Scott not only kept a master list of the objects he was drawing, but also made some important suggestions, the Five Roses sign and the votive ship among them. His wife and creative partner, Christina Poddubiuk, introduced the notion of the codfish as the best object from Newfoundland. She also provided the belt for the illustration of the schoolbooks and made clarifying observations concerning some of the other objects on the list.

This is a magnificent country in which to live, for all kinds of reasons. Yes, there are flaws in the system, inequalities and injustices. But we have the tools to address these problems, and an openness to the idea of attempting to change for the better. In the end I came to realize how much I love Canada, and how fortunate I am that my ancestors were among the waves of refugees and immigrants who, for several hundred years now, have arrived on its shores. I also came more fully to understand the great debt we settlerswhether multi-generational or brand newowe to the First Peoples of Canada, whose territories and ways of life wereand continue to beundeniably altered by our presence.