Contents

Page List

Guide

Cover

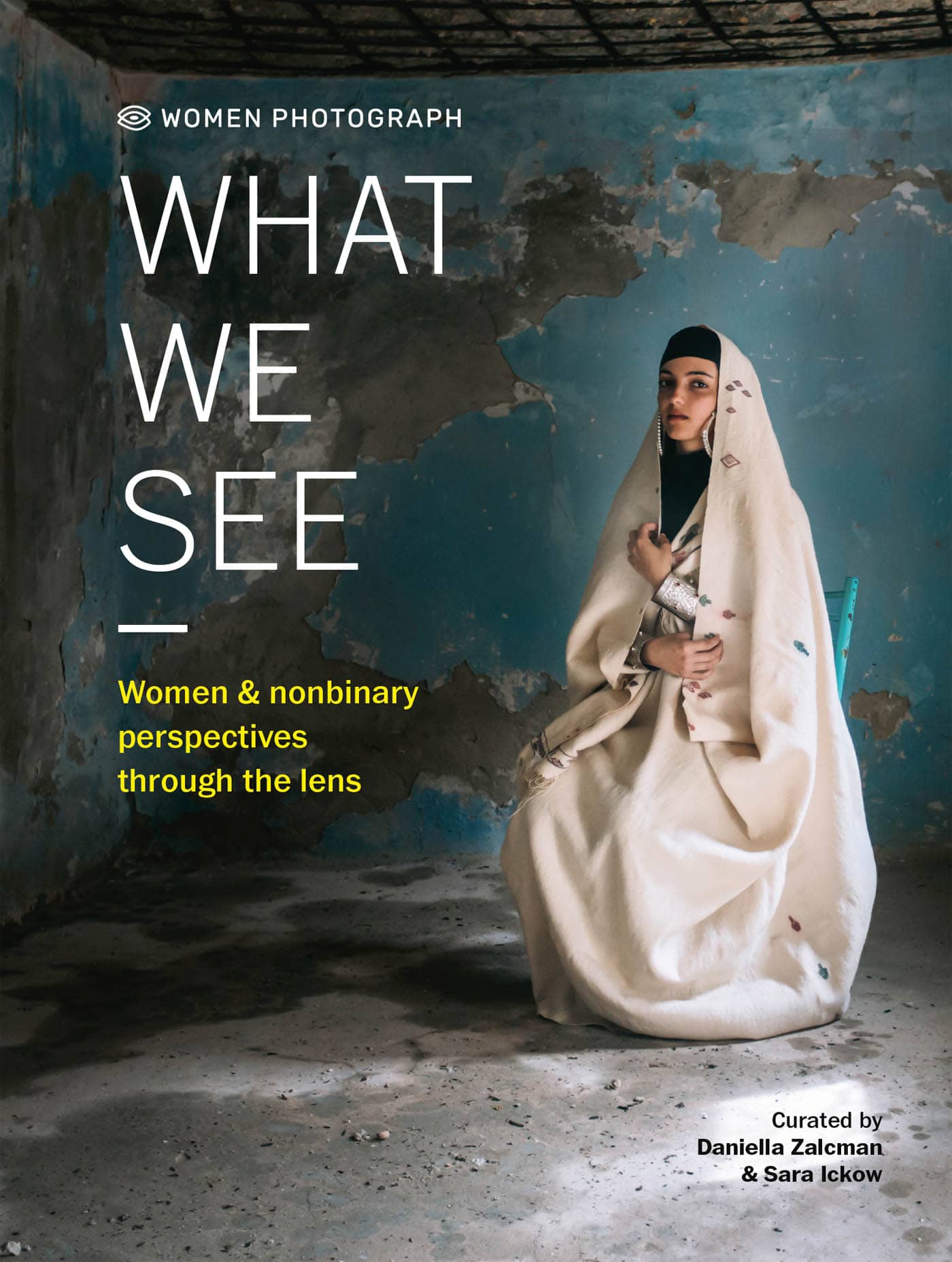

WOMEN PHOTOGRAPH

WOMEN PHOTOGRAPH

WHAT

WE

SEE

Women & nonbinary

perspectives through the lens

Curated by Daniella Zalcman

& Sara Ickow

Foreword

By Kat Chow

What We See is nothing short of breathtaking. Each of these photographs evoked within me a staggering and visceral response, at times bewildering, at times heartrending. As a journalist who has spent years contextualizing our infinitely complex world, I have witnessed time after time how photographs can illuminate our lives in ways that words and audio simply cannot. What We See is certainly no different; I was stunned by how these images drew me into their stories, and how thrilled I was when I recalled that you, too, get to experience this work for the first time. Captured by photographers who are women or nonbinary, these images forge a crucial modern history: one where such perspectives that have historically been ignored behind the lens and in front of it are illuminated with care and respect.

The range of these photographs is remarkable. Perspectives from New Delhi, the Weddell Sea, Vavau in the Kingdom of Tonga, Hong Kong, Cleveland and so many other places, sit alongside one another. They preserve moments of a young woman undergoing surgery to receive the first-ever face transplant, two cholitas in Bolivia mid-fight in a mountain-lined wrestling ring, an examination of Afro-descendants in Mexico, a young woman in Aabey, Lebanon, sitting defiantly in her car following its destruction during a protest in the uprising of 2019.

When I consider what binds the vast array of photos that comprise What We See, the word intimacy surfaces. Intimacy, because the emotional connection to each of these photos arrives swiftly, stirring in me and surely also in you a deep curiosity about their subjects. Intimacy, because this collection ultimately evokes a sense of support: the stories brought to life here elicit the feeling that we are not alone. And that people are bearing witness to, and capturing, the essential stories that animate our lives.

With deep admiration for these talented photojournalists and the lives they have chronicled, I invite you to sit with, and absorb, these photographs. What We See is an impressive feat that will expand your worldview.

Kat Chow is a journalist and writer. She previously was a founding member of NPRs Code Switch, and her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, among many other places. She is the author of Seeing Ghosts, a memoir about family and loss.

Introduction

By Daniella Zalcman, founder of Women Photograph

Photojournalists are tasked with a unique privilege: teaching others how to see.

We introduce our audiences to people and places they may never otherwise encounter, show them ecosystems, conflicts and communities from every corner of the globe. But for as long as photojournalism has existed as a discipline built around broadening perspectives the industry has been dominated by white Western men. That has had a profound impact on our collective visual history: what we choose to document, and why, and how.

It is easy to believe that we, as photojournalists, simply freeze the world around us frame by frame, working as unbiased observers who are fully detached from the events we cover. After all, this is the lie we have told ourselves since the advent of news photography. But, in reality, our identities and lived experiences deeply impact how we access spaces and choose to tell stories. We can only hope to produce nuanced, thorough and respectful journalism with an industry of storytellers as diverse as the communities we document.

I became a photojournalist around 2007 while I was a college student in New York. If I felt the yawning absence of women colleagues and mentors in the press corps at the time, I certainly did not understand how it was impacting my own growth as a photographer. But, by 2016, industry reports were starting to emerge that only 15 to 20 per cent of working news photographers were women and that major news outlets were hiring women photographers at even lower rates. And when interrogated about their assigning practices, editors frequently responded that they just did not know where to find women photographers.

In response, I launched Women Photograph in 2017, a hiring database of women and nonbinary photographers from around the world. Today, our community includes more than 1,600 independent photographers based in 110 countries. And our mission has grown alongside it. We distribute project grants, host annual skills-building workshops, run a mentorship programme that connects early career photographers with editor and photographer mentors, exhibit the work of our photographers at festivals and in galleries internationally, and collect hiring and publishing statistics on the photojournalism industry.

Our long-term objective for the organization is simple: to become obsolete. If Women Photograph is successful in helping the industry achieve true intersectional parity, then the advocacy work at the heart of our organization will no longer be necessary.

Our inaugural book What We See is a broad survey that represents the equally broad careers of our members. The goal is not to make any generalizations about the gaze of women and nonbinary photographers such generalizations are impossible. The directions in which we can expand our traditional understanding of photojournalism are infinite. This book merely begins to hint at the possibilities.

Alongside classic documentary-style images from some of our most acclaimed trailblazers such as Carol Guzy, Susan Meiselas and Lynsey Addario, there is work that defies traditional photojournalistic practice, as in the collaborative images from Koyoltzintli and Charlotte Schmitz, the composite self-portraiture of Haruka Sakaguchi and the constructed images of Sim Chi Yin and Maha Alasaker.

If there is one common thread and a striking one at that it is that much of the work in this book feels quiet, even if it was not made in quiet contexts. Anastasia Taylor-Linds frame of a man in uniform doubled over, next to a bloody stretcher, is a gesture of exhaustion or possibly mourning in the middle of armed conflict. Gulshan Khans photo of a young woman serenely donning a scarf comes moments before she attends a protest in the wake of Israeli forces killing 59 Palestinians. Vernica G. Crdenas image of a Honduran woman being tenderly resuscitated occurs in the relative calm that follows her near-drowning in the Rio Grande. They are all moments wrapped in grief that still allow for other emotions to seep into our understanding of each picture. There is more than just loss.

This comes in stark contrast to the overwhelming number of noteworthy works in photojournalism that centre violence. We build our history textbooks around war and famine and natural disasters, more or less creating a chronology of the traumas inflicted on and by humans throughout our existence. Journalists are similarly drawn to the worst human experiences partially because our work often serves as evidence, and partially because many of us do this work to live up to the words of Joseph Pulitzer III, We will illuminate dark places and, with a deep sense of responsibility, interpret these troubled times.

WOMEN PHOTOGRAPH

WOMEN PHOTOGRAPH