Contents

First published in the United States of America in 2021 by Chronicle Books LLC.

First published in the UK in 2021 by Ilex, an imprint of

Octopus Publishing Group Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.octopusbooks.co.uk

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

Text Copyright Emma Lewis 2021

Design and Layout Copyright Octopus Publishing Group Ltd 2021

Commissioned by Ellen Sandford ONeill

Publisher: Alison Starling

Commissioning Editor: Richard Collins

Managing Editor: Rachel Silverlight

Art Director: Ben Gardiner

Designer: Charlotte Heal Design

Picture Research Manager: Giulia Hetherington

Copy Editor: Jane Ace

Proofreader: Anjali Bulley

Production Manager: Caroline Alberti

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Emma Lewis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

ISBN 978-1-7972-1477-1 (epub, mobi)

ISBN 978-1-7972-1383-5 (hardcover)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Whose Stories ARE WE TELLING?

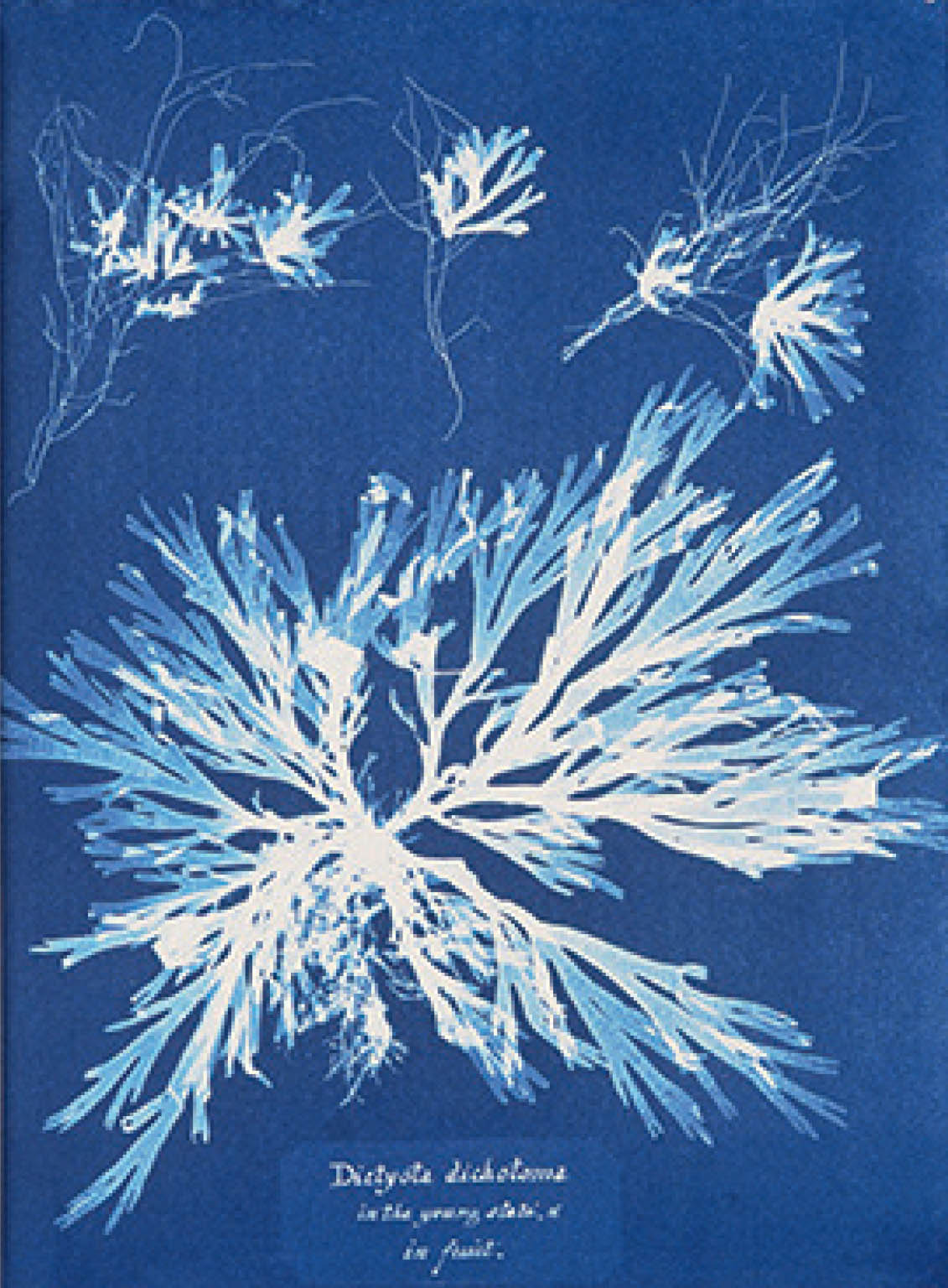

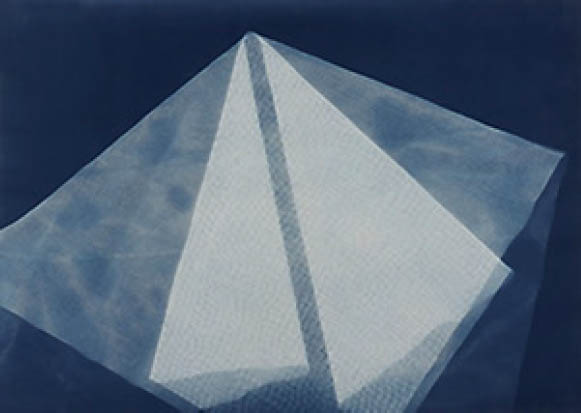

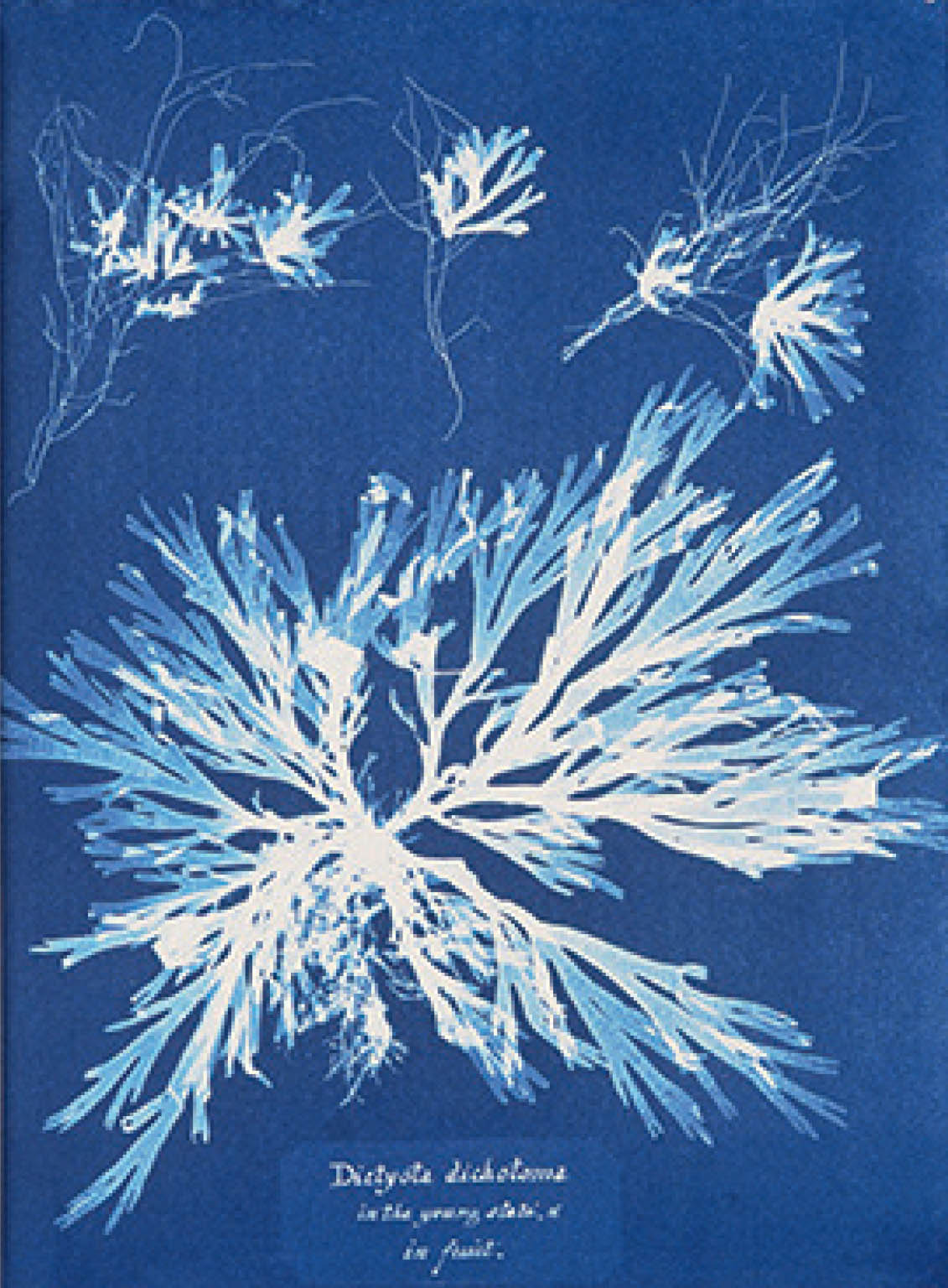

Anna Atkins, Dictyota Dichotoma, in the Young State; and in Fruit, c. 1850,

from Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, c. 184353

I n 1839, in the rarefied halls of the Acadmie des sciences, Paris, photography was introduced to the world in the form of the daguerreotype, marking a technical and cultural milestone that would forever change how we see the world and with that, how we see ourselves. The announcement coincided with major international political shifts: continued colonial expansion into Asia and Africa, the abolitionist movement to end slavery in the US growing strength, and the early days of the struggle for womens rights. In the same year, also in Paris, a philosopher named Charles Fourier had coined the term fminisme, which put a name to the intellectual debates that had been gathering momentum for the past century and would soon coalesce into something we recognize today as modern feminism.

For the past two hundred years, these histories have run parallel. A task of feminism is, to paraphrase the American writer Rebecca Solnit, to make women credible and audible; photography has done both. It has been a reliable witness to womens movements and made the causes for which they fight visible. It has also created images of femininity and sexuality that they have had to push back against, often employing their own images as a weapon. Likewise, feminism, as a set of ideas, has shaped how photographers have approached their medium and how the rest of us have made sense of it. Yet the traditional history of photography (that which has been assembled over the past eight decades or so) tells us that all too often, these ideas are overlooked.

You are likely familiar with how that traditional account goes. It is white, Western and it is overwhelmingly male. Over time, attempts have been made to restore womens names into that history, and indeed some have stuck. But for every Julia Margaret Cameron two women who have finally received due recognition many thousands have been ignored, or their biographies have been flattened and told as though they were appendages to the men in their lives. The same old stereotypes persist, too: the genteel lady hobbyists photographing to while away the hours; the gung-ho pioneers blazing a trail to the front line. But where are the working-class women who set up studios to make ends meet? The ordinary folk quietly recording their communities because they knew that no one else would? Where are the thousands of others whose stories did not quite fit the mold?

Its time for some new narratives.

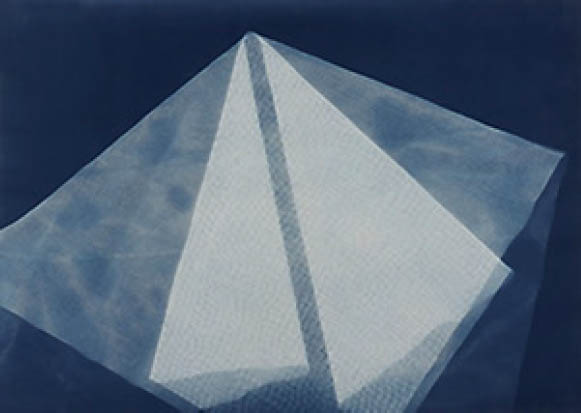

Barbara Kasten, Untitled 74/3, 1974, from Photogenic Painting, 19746

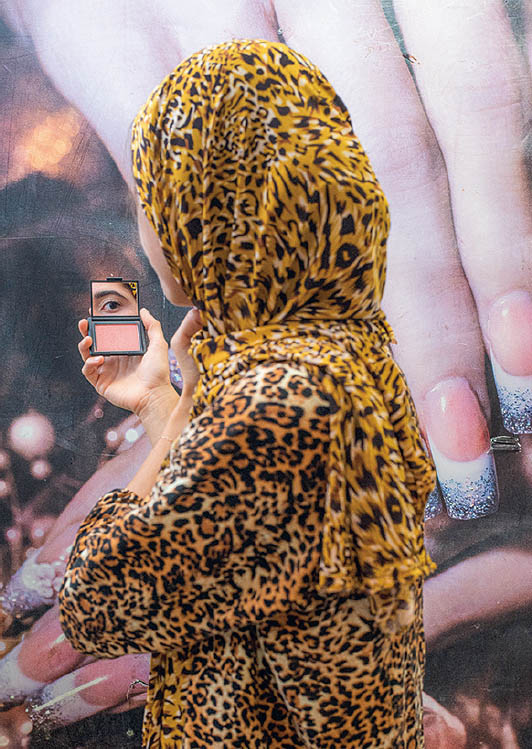

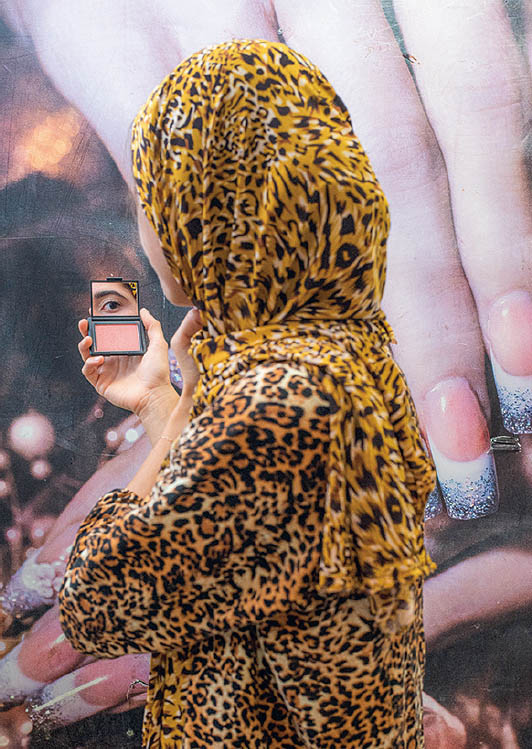

Farah Al Qasimi, Woman in Leopard Print, 2019

Pixy Liao, Its never been easy to carry you, 2013, from Experimental Relationship, 2007ongoing

Photography, A Feminist History, explores how womens rights and societal attitudes toward gender across the world have shaped who have become photographers, the kinds of work they have made and how their stories have been written and rewritten over time. It is not a documentation of feminism illustrated through photography (that would be an altogether different book) but an account of some two hundred years of photographic practice told from a feminist perspective. Each chapter focuses on one theme or approach during the decades in which it emerged or are especially significant to its development. We begin with studio photography, the first forum in which women could gain a professional foothold, and end with self-portraits born of online culture. In between, we see the development of photography as an art form in avant-garde movements and the use of the camera to record both public and private life. We find photographers who have refused the idea that they had a womans eye and those who have put their gender front and center. We meet still others who were integral to shaping ideas about gender and sexuality both behind and in front of the camera.

Each chapter includes artists who are established and lesser-known, and from all corners of the globe. Suffice to say, they represent a history not the history. Any survey is inherently incomplete and imperfect. A different author (even the same author, on a different day!) will have made different choices. Added to this subjectivity is the fact that feminism is sprawling and complicated, and ideas about what makes a feminist change all the time. One description is regularly attributed to British author Rebecca West, who pithily said she was called a feminist when she expressed sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat. Both give us a straightforward description of a position that is anything but.

In the past two hundred years of photographys life, innumerable feminisms have emerged: philosophies or movements whose concerns were organized around the personal characteristics and circumstances of the individuals behind them and the time and place in which they lived. Some of these individuals would describe themselves as feminists and use the term feminism, others rejected the term for what it stood for at that time, and others were active in contexts where the word simply was not in use. This book uses feminism as a helpful catch-all term for these different alliances and ideas when it is not possible to be specific, or to include endless caveats. Rather than adopting the perspective of one feminism, it takes a broad view that considers the internal differences, disagreements and blind spots to be not only integral to making sense of the messy business of feminism but also what makes it so interesting. Somewhere within these tangled ideas we can find fresh and illuminating ways of thinking about photographs and their makers, and a set of guiding principles as to how to organize them into what we are calling a feminist history.