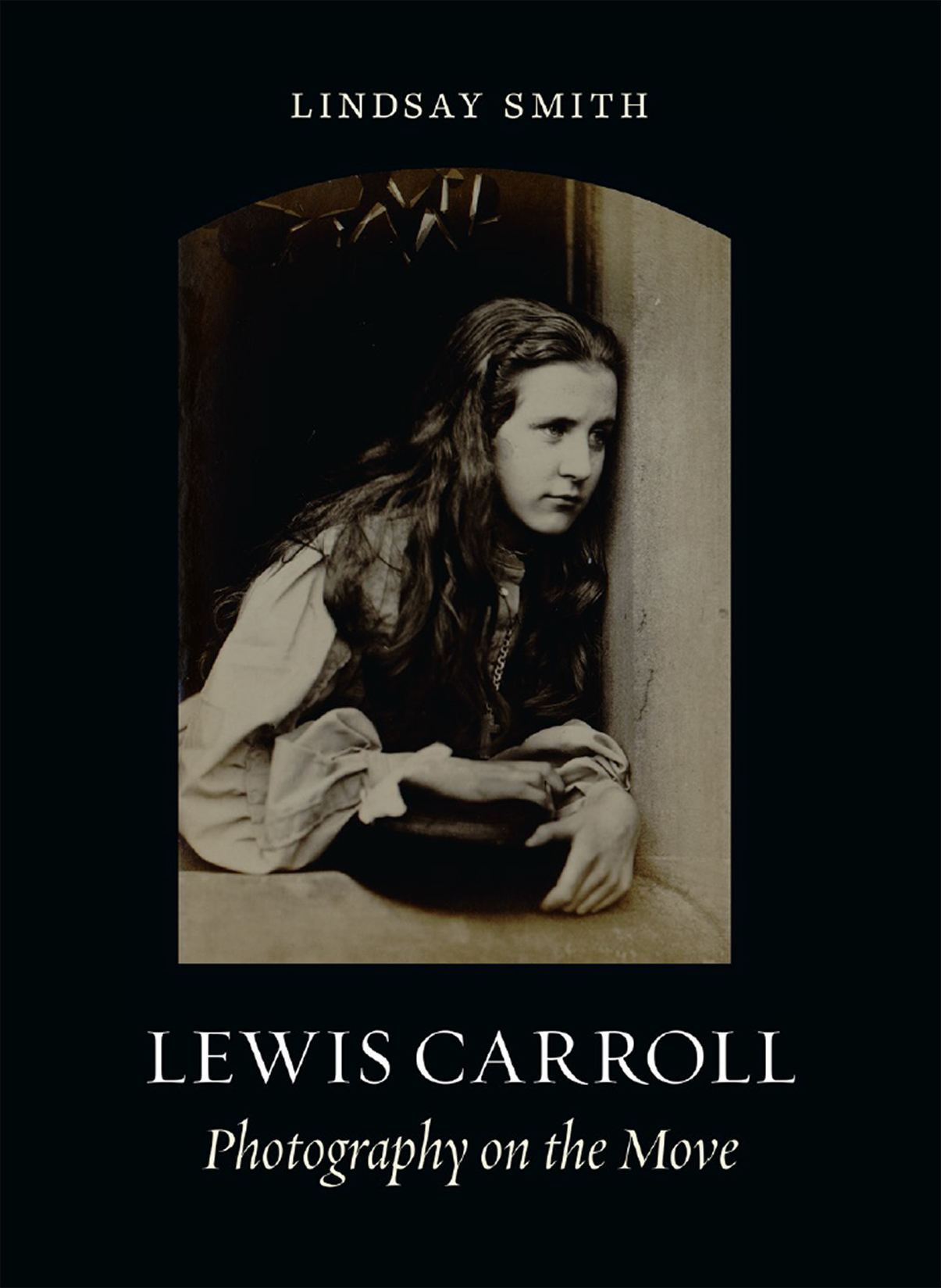

Lewis Carroll

Photography on the Move

Lewis Carroll

Photography on the Move

Lindsay Smith

REAKTION BOOKS

For my mother, Brenda Smith, and in memory

of my father, Weston Smith, 19282014.

Published by

Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2015

Copyright Lindsay Smith 2015

The author and publishers gratefully acknowledge a grant from the Marc Fitch Fund towards the costs of publishing this work

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Limited

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780235455

Contents

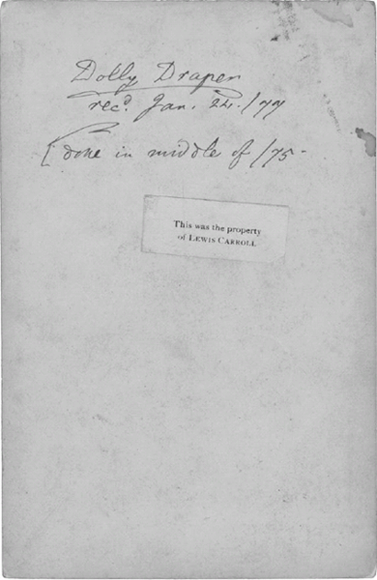

1 Edmund Draper, Dolly Draper, 1875, albumen print.

Introduction

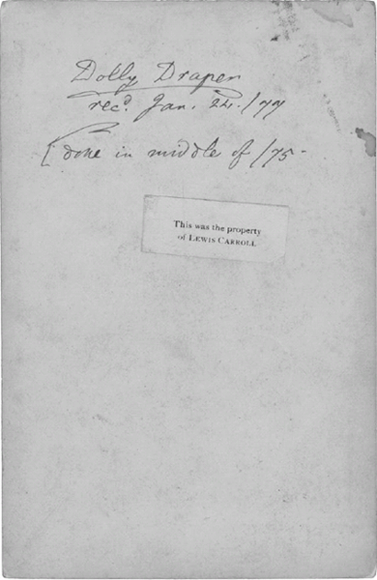

O N 24 JANUARY 1877 the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (18321898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, wrote to Ellen Dolly Draper, daughter of Ellen and Edward Thompson Draper, thanking her for a photograph of herself she had sent to him.), the sitters identity is clear from the props to which his letter refers. For the cap is very like the one worn by Xie Kitchin in his portraits of her from the same decade and a large sleeping dog, mentioned in Carrolls letter, is unmistakably present in the composition. Yet, with its relaxed garden setting, the mood of the photograph is different from his.

On 5 February of the same year Carroll sent a photographic portrait of himself to Dolly Draper, who remained for him at this point one of three unseen little friends. The carte de visite, an assisted self-portrait possibly taken in 1872, was printed at Henry Peach Robinsons studio ( While there are no precise details of those images sent by Edward Draper, Carrolls subsequent note to him, I shall specially treasure those of Dolly (VII, 30), indicates that among them were several of the child. In all probability they resembled the extant photograph and, escaping the trappings of professional studios, their informality appealed to Carroll.

2 Reverse of Dolly Draper, 1875, with Lewis Carrolls inscription.

Although both of these encyclopaedic documents are now lost, the recorded existence of thousands of photographs and letters testifies to an important, though largely unremarked, closeness for Carroll between the two forms of expression, photography and letter writing. Letters facilitated connections between photographs and places. They did so not simply by detailing sittings for Carrolls camera or by recording the circumstances of his purchase on his travels of cartes de visite. Rather, they provided a discursive space in which to explore conceptual connections, often intricate ones, between the medium of photography and particular locations.

This book is concerned precisely with such connections. It recognizes as central to them, as evident in the case of Dolly Draper, photographs of female children. The reference in my title to photography on the move incorporates the geographical movement of Carroll as a nineteenth-century amateur photographer along with the migration of photographs themselves to places far from their points of origin. I range, therefore, from instances when Carroll travelled with his camera to those photographs he bought on his travels and had made in professional studios. His monumental trip to Russia without a camera in 1867, the subject of demonstrates, they fed his fascination for photography just as his experience of particular locations was itself shaped by photographic interests.

3 Lewis Carroll, Self-portrait, 1872(?), albumen print.

It also gestured towards emerging cinema.

Carroll bought his first camera on 18 March 1856 from Ottewill and Company in London, nine years before the publication of what would become his most well-known book, Alices Adventures in Wonderland. Costing 15, the purchase represented a serious investment for a prospective amateur photographer and when the portable folding rosewood box arrived on 1 May he began to experiment with spoiled collodion that his friend Reginald Southey had given to him (II, 67). With Southeys help, Carroll was soon adept at the new technology and for the next 24 years using the wet collodion process that required considerable skill to secure good results he took, processed, mounted and catalogued photographs at every available opportunity.

Not all amateurs were able to master with the assurance Carroll did the photographic method made available by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851.

The physical act of taking a photograph, from the initial sitting to the final print together with those technical skills it required, fascinated the author of the Alice books and preoccupied him for a significant period of his life. He began photography at a time when the medium was still relatively new and held considerable intrigue. During its early decades photography possessed a peculiar cultural status, one signalled by its combined mechanical, physical and chemical origins. Unlike those manual methods of reproduction that preceded it, such as engraving, photography eliminated the trace of a hand; the causal, or indexical, connection to a referent determined the unique materiality of the photographic print. By a seemingly perfect correspondence with the object, together with those negative/positive shadow/light dichotomies that mark a temporal dimension to its presence as burnt into the plate, a photograph is always belatedly the thing it represents.

In 1880 Carroll recorded taking what appears to have been his last photograph and scholars have speculated upon this apparently sudden termination of one of his favourite activities. Some argue that he lost interest in the medium. Others cite as a primary cause the replacement of the wet plate photographic process by the dry plate. Still others eschew technical reasons in favour of personal ones, suggesting that Carrolls concern over increasing gossip about his relationships with girls and young women determined his decision.

Carroll was therefore as much an owner and consumer of photographs as a maker of them. Yet his reputation as an auteur, an accomplished practitioner, has to some degree obscured his identity as an avid purchaser and collector of cartes de visite and other photographic forms. Carroll owned many studio and amateur portraits of children. Some of these originated from sittings he superintended. Others he sourced from studios and shops. Some he solicited from friends and acquaintances, or, as in the case of Dolly Draper, from children themselves. Carroll notes, for example, in his diary for 14 June 1869, a visit to meet the mother of a child, Mary Beatrix Tolhurst, whose photograph he had admired at the house of an acquaintance (VI, 89). On 3 August of that year he invited Charles and Elizabeth Tolhurst of Bracknell to Oxford so that he might photograph Beatrix. Though Carrolls photographs from that session have not come to light, I have located a