T HIS IS A B ORZOI B OOK

P UBLISHED BY A LFRED A. K NOPF , I NC .

Copyright 1972 by Tom McHugh

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Convention. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

McHugh, Tom The time of the buffalo.

Based on the authors thesis, University of Wisconsin.

Bibliography: p. 1. Bison, American. I. Title.

QL737.U53M3 1972 599.7358 72-2242

eISBN: 978-0-307-82835-4

v3.1

To my mother and father

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T HIS BOOK OWES ITS GREATEST DEBT TO COUNTLESS individuals who cannot properly appreciate their duethe buffalo in several refuges who patiently, stoically, sometimes indignantly permitted themselves to become subjects of my investigations. To the directors and managers of these refuges, however, I would like to express my gratitude:

In Yellowstone National Park, observations were carried on with the cooperation of Superintendent Edmund B. Rogers and his staff, most particularly Chief Park Naturalist David de Lurie Condon. Additional assistance came from Head Animal Keeper David W. Pierson, biologists Robert E. Howe and Walter H. Kittams, as well as Mary Meagher, W. Verde Watson, W. Leon Evans, Stanley McComas, John S. Bauman, Frank T. Hirst, Joseph Way, and Lee L. Coleman.

In other refuges, ready assistance was extended by Earl Semingsen and H. R. Bob Jones of Wind Cave National Park; by Gordon Powers and Clark Stanton of the Bureau of Indian Affairs at Crow Agency, Montanaand also by the Crow Indian Tribe; by Ernest J. Greenwalt, Claude A. Shrader, and Richard J. Hitch of the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge; by John Schwartz, Cy Young, and George E. Mushbach of the National Bison Range; and by Eliot Davis and K. C. Sunny Allan of Grand Teton National Park.

For their inspiration, understanding, and many helpful suggestions, I am especially grateful to Paul Brooks, John Livingston, and Roger Tory Peterson.

Many other persons have most generously furnished information and reference material for this study: Margaret Altmann of the University of Colorado; Georgia and Bud Basolo of the B-Bar-B Buffalo Ranch; Oliver Burris of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game; Robert A. Elder, David H. Johnson, Margaret Halpin, and Meredith Johnson of the Smithsonian Institution; Jack Hogben of Walla Walla, Washington; Julian Howard of the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge; Barbara Lawrence of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University; Raymond J. Parker of La Grange, Illinois; H. R. Peters and J. B. Campbell of the Canada Department of Agriculture; Zdzislaw Pucek of the Mammals Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Bialowieza, Poland; C. Bertrand Schultz of the University of Nebraska State Museum; and Michael Z. Zablocki of the Central Bison Park, U.S.S.R. Still other persons have been helpful in both thought and deed: Henry Babcock, Harry Brown, Frank and John Craighead, Cally Curtis, Jack Douglas, Robert C. Fields, Warren Garst, George Hobson, Allen Keast, Jane Kinne, Reginald Laubin, Holly Leek, Ruth Laurie, Roberta Mayo, S. J. Olsen, Morris F. Skinner, and Tom Smith. I am also indebted to numerous scientists and chroniclers whose writings have yielded much information; most of these observers are listed in the bibliography at the end of the book.

Photographs from the files of The Vanishing Prairie were kindly furnished by Tom Jones and George Sherman of Walt Disney Productions; credit for the original work goes to the photographers themselvesJames R. Simon, Hugh Wilmar, and Warren Garst.

This book had its beginnings in a research study I undertook for a doctorate at the University of Wisconsin. Funds for the project came from the Jackson Hole Biological Research Station of the New York Zoological Society; the director of the station, James R. Simon, lent considerable support to the endeavor.

For his assistance in the execution of the research and for his advice on the book that eventually resulted from it, I am most deeply indebted to Professor John T. Emlen of the Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin. His guidance, aid, and encouragement deserve major credit for bringing this study to fruition.

The text itself owes much to the labors of Victoria Hobson, who, over a period of years, unselfishly devoted her time to improving the style, structure, and organization of my original chapters. Her way with words has illuminated the writing and added immeasurably to the final work.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

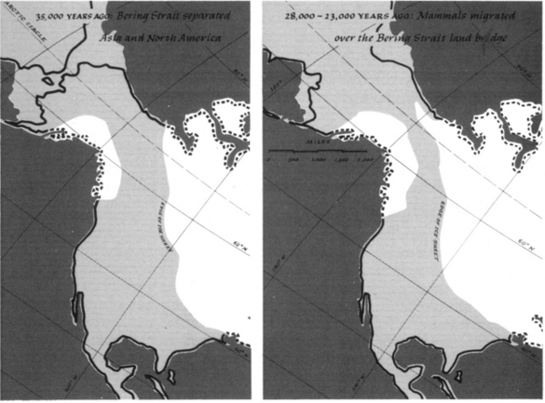

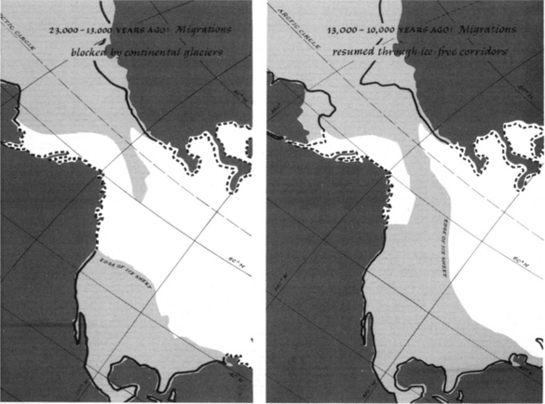

BERING STRAIT LAND BRIDGE

BUFFALO RANGE

BUFFALO ATLAS

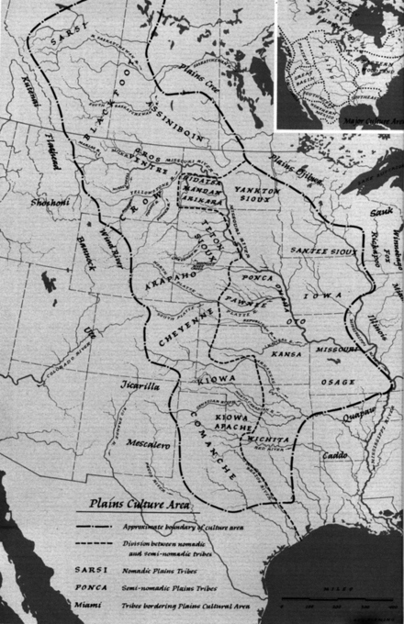

PLAINS CULTURE AREA

The Bering Strait Land Bridge During the Last Part of the Ice Age

NOTE : Time spans are approximate, us are the general shapes of the land masses and ice sheets.

INTRODUCTION

E ARLY IN THIS CENTURY, THE N ATIONAL M USEUM OF Canada sent an anthropologist to the plains of Alberta to record what he could of the native culture of the Sarsi before the tribe took up the ways of the white man. As the Indians described customs and beliefs that dated back to the time of the great buffalo hunts, they related their particular version of the hereafter. They imagined that a deceased mans soul and shadow wandered away to a cold sandy land far to the east, there to dwell with other departed tribesmen, to sit around a campfire in the center of a ragged tipi and gnaw on the parched bones of buffalo that had perished long ago. Sarsi warriors accepted the possibility of death and a journey to this barren Elysium stoically, even without fear. Perhaps because they had been living comfortably off the meat and hides of the buffalo roaming the northern prairies, the mythical tableau of a wasted plain filled only with the bones of the once great herds was no more than a remote vision, a bleak conjuration of aging shamans.