Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

202 Warren Street

Hudson, NY 12534

www.papress.com

2020 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved.

All images The Estate of Paul Rand

On Good Work 2019 George Lois

All drawings from the collection of Steven Heller

Authors proceeds will be put toward the Paul Rand Design Award, SVA MFA DESIGN / The Designer As Entrepreneur

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright.

Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Moleskine is a registered trademark.

Editor: Eugenia Bell

Layout and typesetting: Kristen Ren, Paul Wagner

Series design: A+G AchilliGhizzardiAssociati

Special thanks to: Paula Baver, Janet Behning, Abby Bussel, Jan Cigliano Hartman, Susan Hershberg, Kristen Hewitt, Stephanie Holstein, Lia Hunt, Valerie Kamen, Jennifer Lippert, Sara McKay, Parker Menzimer, Wes Seeley, Rob Shaeffer, Sara Stemen, Jessica Tackett, Marisa Tesoro, Paul Wagner, and Joseph Weston of Princeton Architectural Press

Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lois, George, interviewer. | Heller, Steven, writer of introduction.

Title: Paul Rand : inspiration and process / Steve Heller.

Description: New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2019. | Moleskine Books.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009990 | ISBN 9781616898595 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781616898854 (epub, mobi)

Subjects: LCSH: Rand, Paul, 19141996Notebooks, sketchbooks, etc.

Classification: LCC NC999.4.R36 A4 2019 | DDC 741.6092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009990

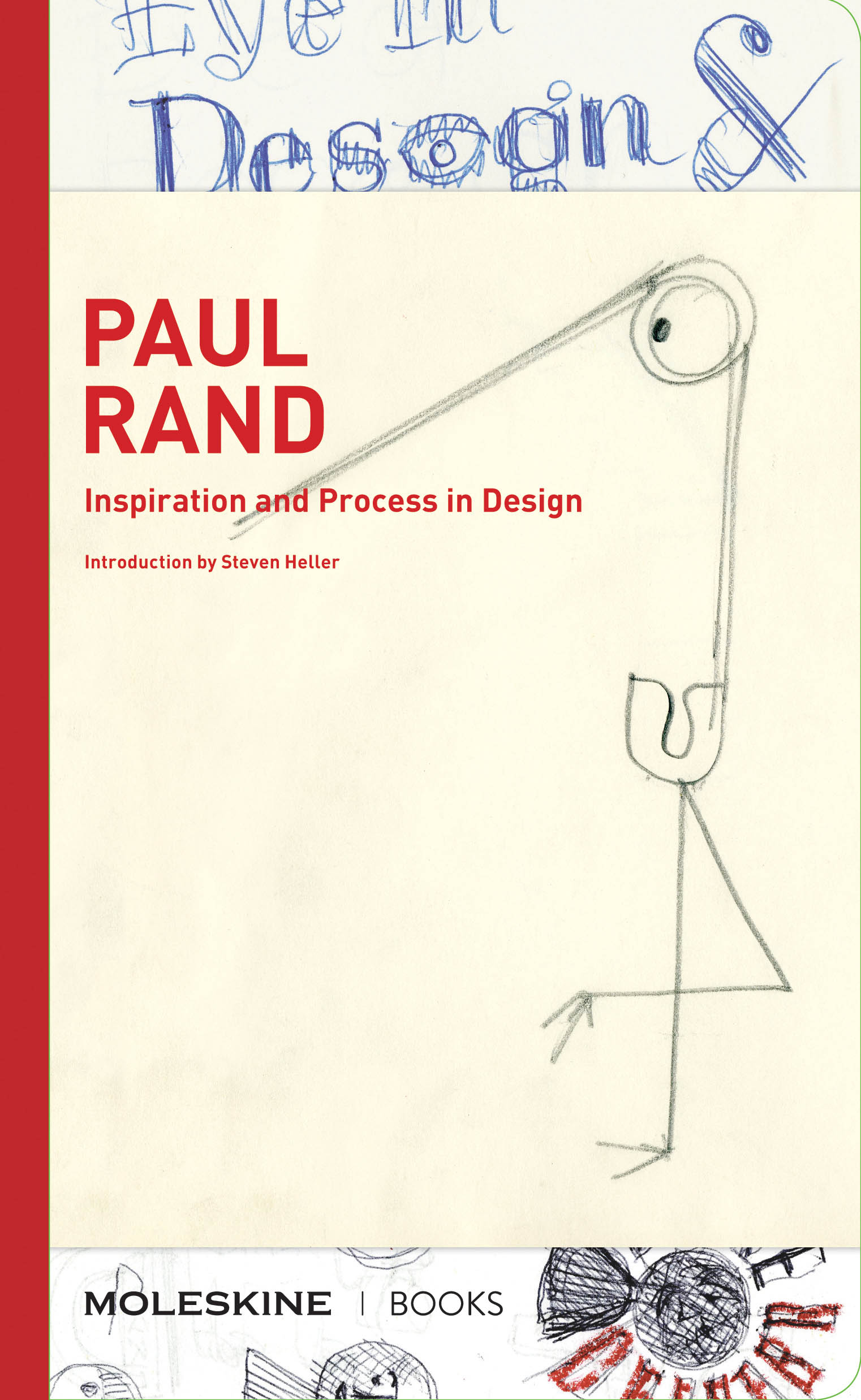

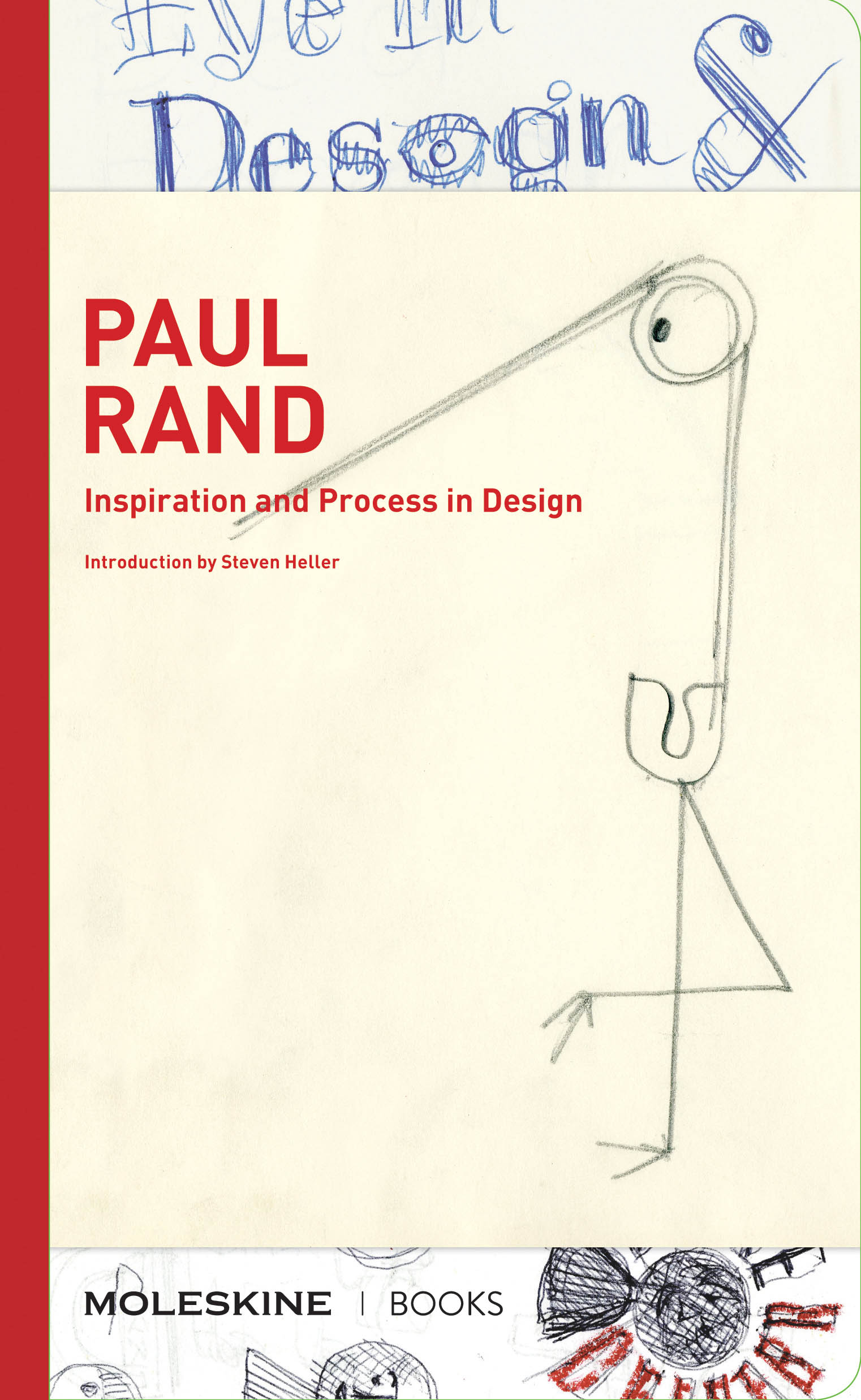

Inspiration and Process is a series of monographs on key figures in modern and contemporary design that emphasizes the value of freehand drawing as part of the creative process. Each volume reveals secrets and insights, and conveys observation techniques, languages, characters, forms, and means of communication.

Contents

Writings

Sketching for Fun and Profit

Steven Heller

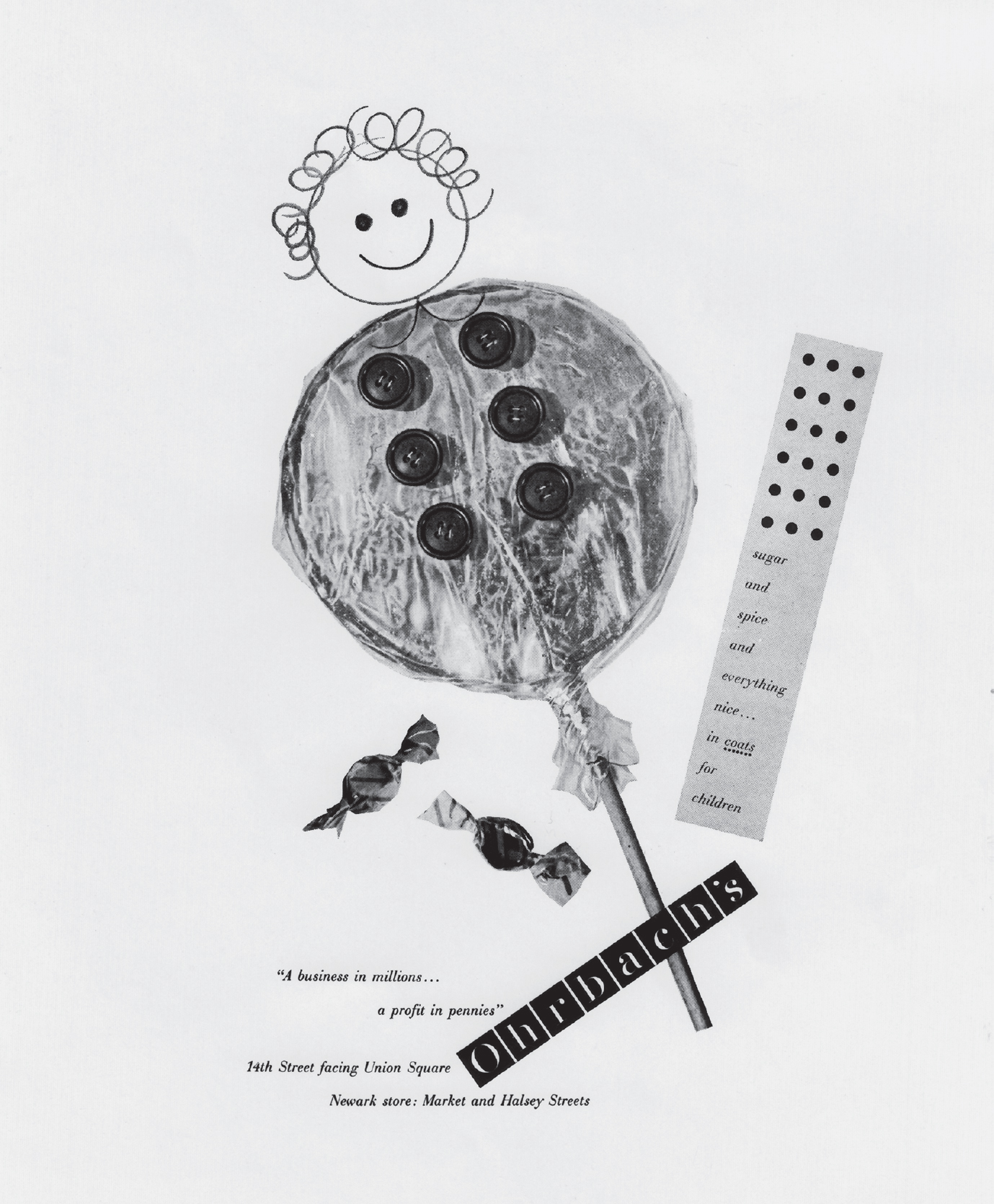

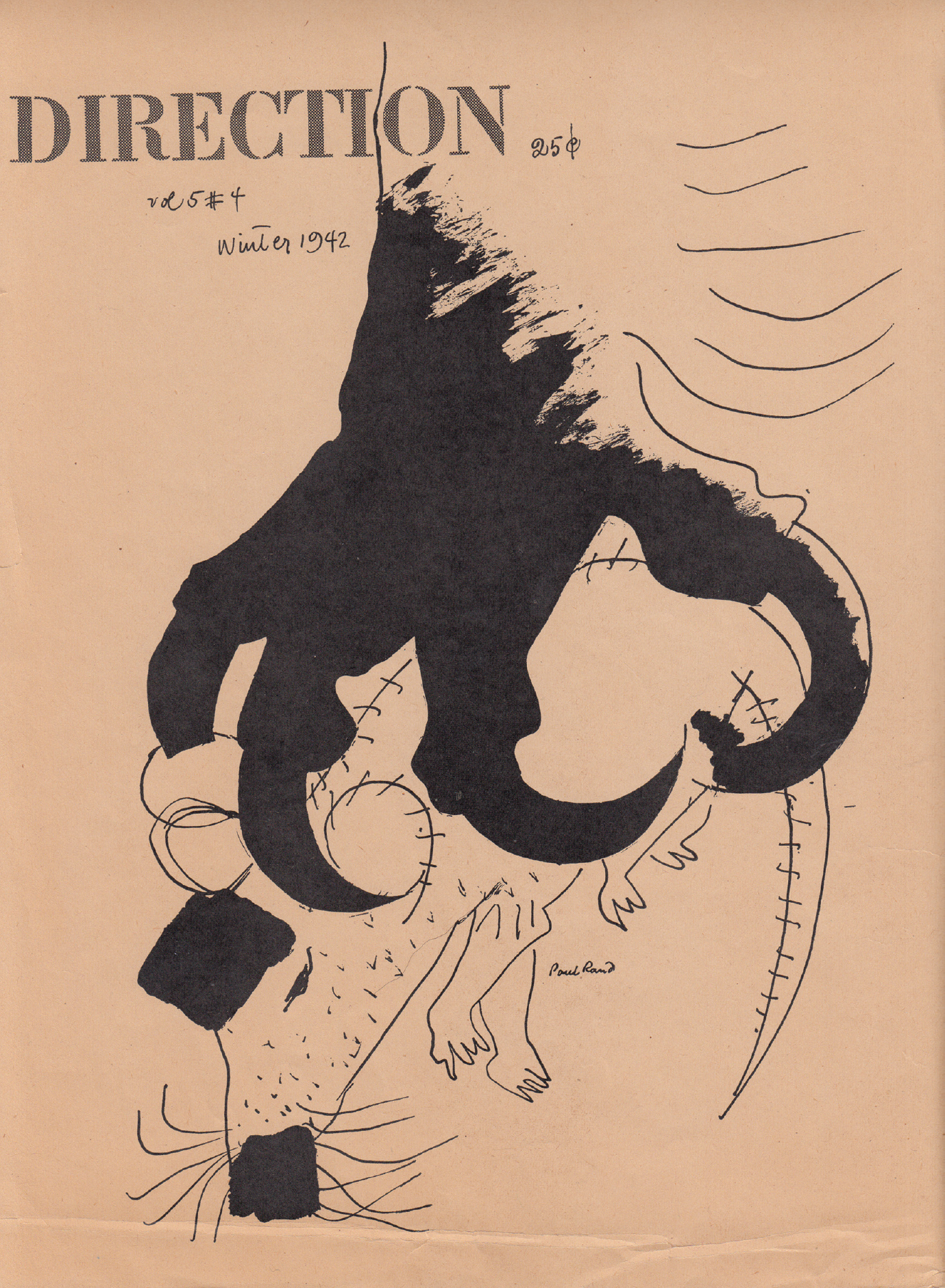

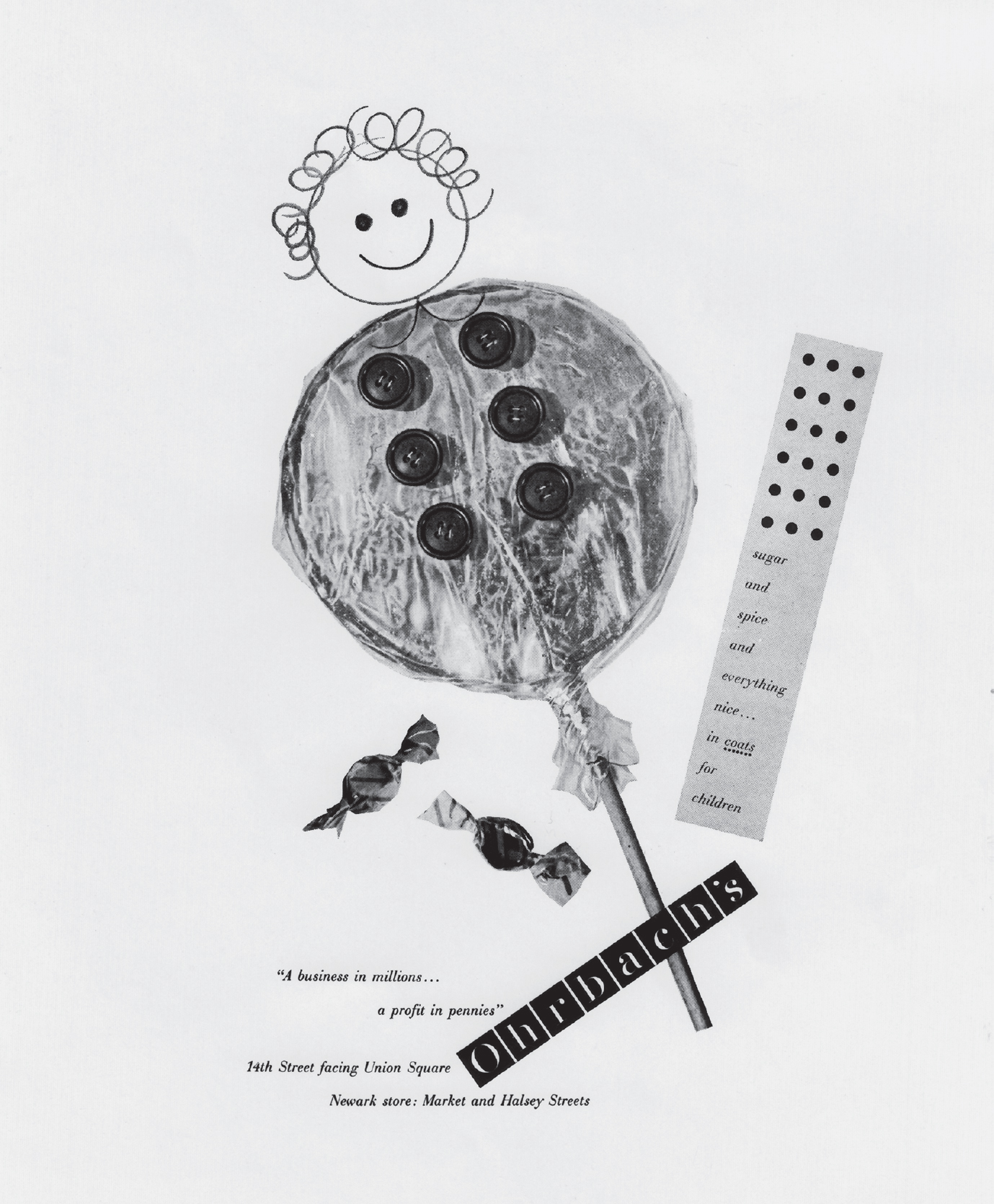

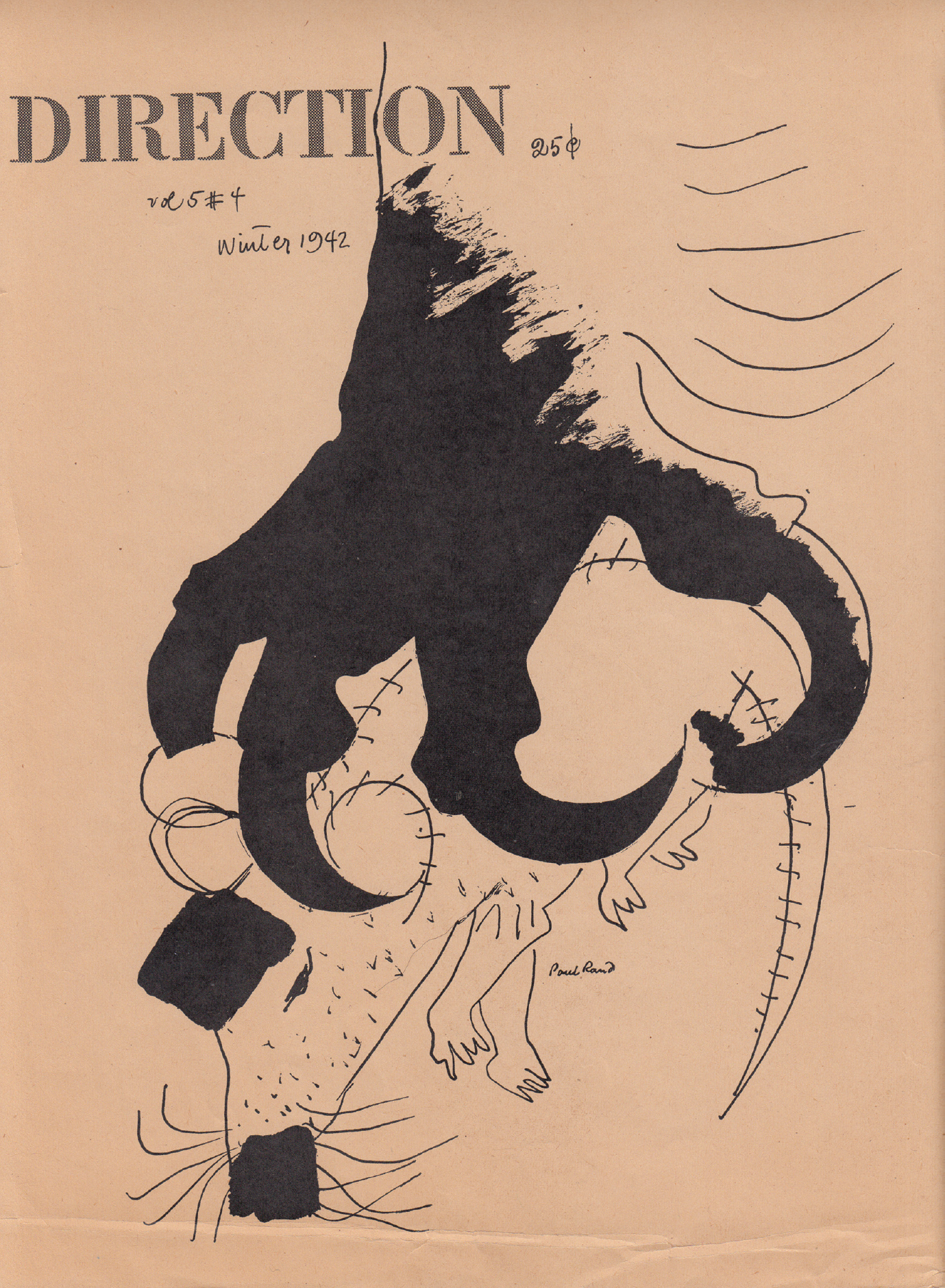

When a client would call him with a potential logo assignment, Paul Rand impulsively made pencil sketches. Even if Im not interested, if I have no time, or if I dont like the subject, he told Artograph magazine in 1988, I sit down and figure out a design solution. Scribbling was a natural urge, he continued, Its animal instinct, like a cat goes after a mouse.

Every artist and designer makes drawings to trigger their thought process. Abstract or representational, visual ideas originate in the mind, then emerge from pencil, pen, and brush. However, what is done with those marks on paper differs from individual to individual. Some keep well-ordered, numbered notebooks, cataloging their process; others fill wastebaskets with their junk. Rand was a consummate sketcherand his file cabinets were stuffed with this stuff. Why he saved what he did is a mystery.

Born in 1914, Peretz Rosenbaum was raised by Orthodox Jewish immigrant parents who believed that the visual arts were neither a viable means of earning a living nor representative of a devout religious life. Yet art was somewhere in his DNA waiting to break away from that of his shtetl forebears. The native Brooklynite, who eventually changed his first name to Paul and adopted a family members surname, Rand (it balanced nicely, with four letters in each name), was decidedly more devoted to making images and learning about anything and everything artisticfrom architectural design and decoration to drawing, painting, and sculpture (additionally, a natural interest in newspaper funny pages also influenced some of the drawings he routinely produced for his own pleasure).

The unique cache in this book was sent to me via Rands friend Bob Burns, who has been organizing and preparing the remaining heap of Randian artifacts since the designers death in 1996. Some were to be donated to study centers, others sold at a 2018 auction in Chicago.

I was grateful to be given a goody bag of drab green Pendaflex files (I was surprised that the folders were not the same bright, happy colors he used in his work) stuffed with bizarre and delightful minutiae, including hundreds of newspaper clippings by writers who interested him, holiday cards from friends and acquaintances, unsolicited manuscripts from admirers, proofs and comps for logos, and dozens of photographs of artworks that had gone into his own books.

Among these rarities is an unpublished essay titled Twenty-Four Hours a Day, a chapter for an unfinished book he had worked on in the early 1960s that later, perhaps, evolved into his monograph Paul Rand: A Designers Art. In this essay I believe he explains why he saved the files that are now in my possession. The act of creativity is almost as much a mystery to the artist himself as to the layman, he wrote. Nevertheless I do believe that for the most part and for most artists inspiration often comes from unromantic, even unlikely sources... As far as I am concerned, inspiration is simply a flowery term for the particular way in which the artist gathers experience and reacts to it. As though providing a key to his own hoarding, he added: an artist accumulates things and borrows objects from the sea and the scrap heap. Then makes mental notes and records impressions on tablecloths and newspapers; he forages and is omnivorous.

As far as foraging goes, the thickest bulging folder in the batch is labeled Sketches and contains individual scraps of everything from male and female nudes to baseball players, soldiers, and childrencartoons, life studies, and scrawls galore. Another is filled with a few molding spiral bound sketchbooks that include partially filled pages with travel scenes and indiscriminate doodles. Another, my favorite, labeled Monkeys and Elephants, is the only one that sticks to a specific, if enigmatic, theme. If anyone knows why Rand kept a folder with the title Monkeys and Elephants, Id like to hear from you. It is not a fat folder: maybe a couple of dozen comicalities drawn on paper, cardboard, and a few napkins. While he included elephants (as well as tigers, rabbits, frogs, and horses) in some of his advertising and childrens book illustrations, to my knowledge he never used monkeys. I kind of understand why he liked elephants. There is something ineffably modern about the pachyderms otherworldly form (see the Eames Elephant stool). But Rands monkey business was, and is, an unsolved mystery.

Rand was always drawing. It was the core of his oft-discussed play principle. I dont think play is done unwittingly, he told me. At any rate, one doesnt dwell over whether its play or something more seriousone just does it. So, it is safe to assume that sketchily monkeying around was that conscious-cum-unconscious act of creativity he talked about. If there was not a semblance of self-consciousness, he would not have kept a file, right? On the other hand, being that primates are mans closest ancestor, maybe they reminded him of certain clients. I can see Rand in my minds eye, wittingly drawing a chimp while talking to one of these guys on the telephone. Of course, this is simply a theory, but so is evolution.

Next page