Contents

List of Figures

Page List

Guide

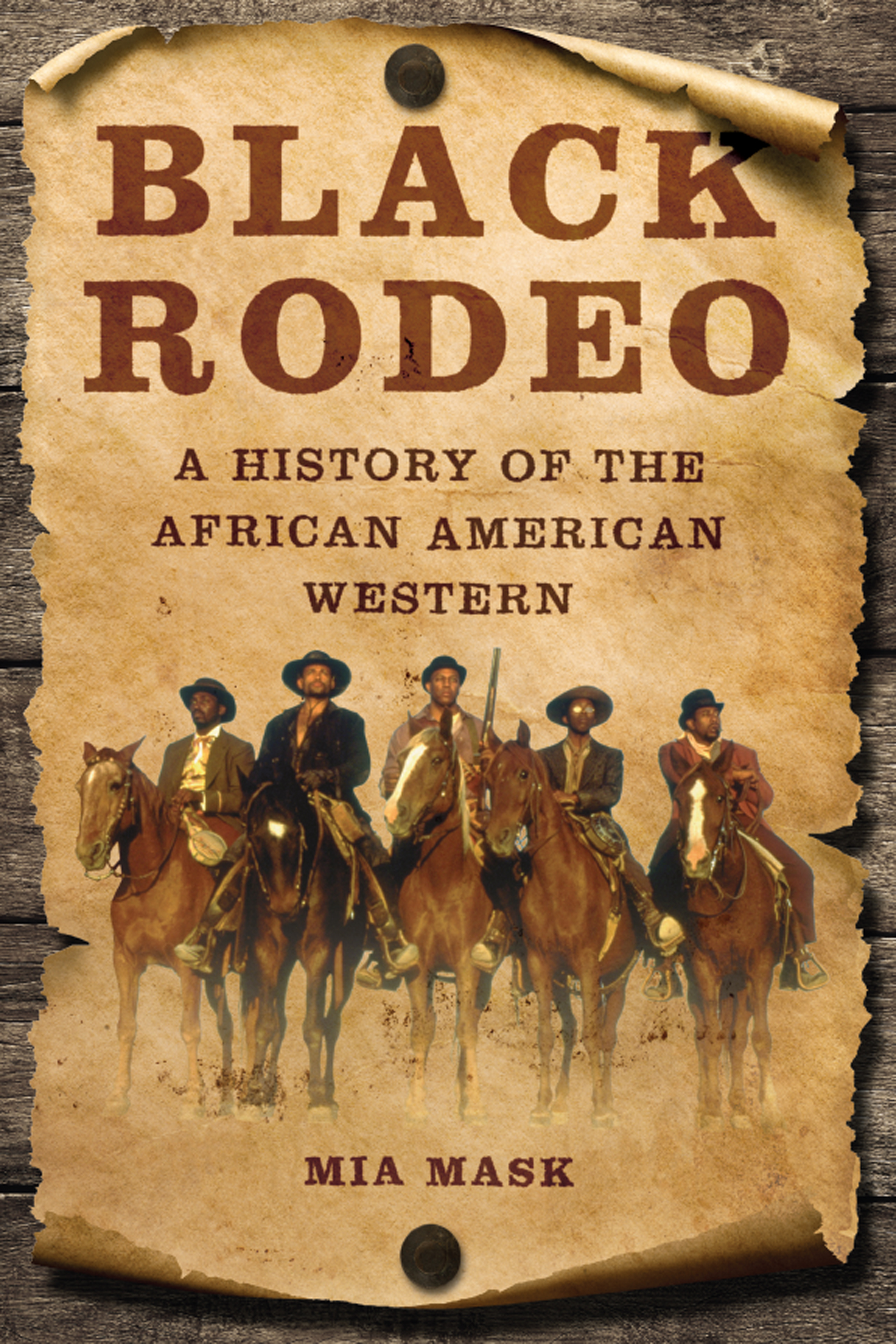

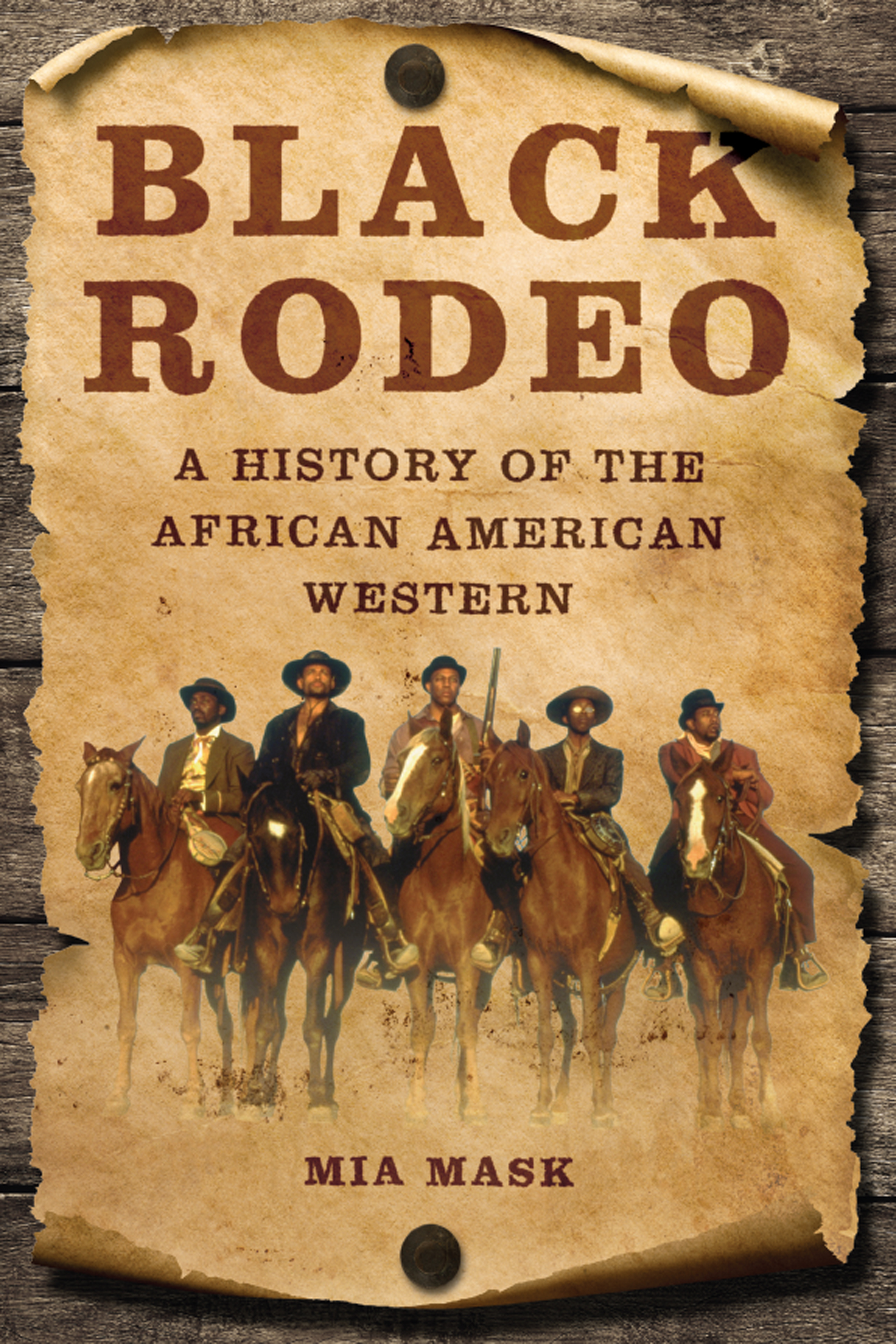

black rodeo

black rodeo

a history of the african american western

mia mask

2023 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Much of was previously published in Poitier Revisited: Reconsidering a Black Icon in the Obama Age, eds. Ian Gregory Strachan and Mia Mask (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mask, Mia, author.

Title: Black rodeo : a history of the African American western / Mia Mask.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references, filmography, and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022030917 (print) | LCCN 2022030918 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252044878 (cloth) | ISBN 9780252086977 (paperback) | ISBN 9780252054020 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African Americans in motion pictures. | Western filmsUnited StatesHistory and criticism. | African American cowboys in motion pictures. | African Americans in the motion picture industry. | African American cowboys. | Race in motion pictures. | BISAC: PERFORMING ARTS / Film / Genres / Westerns | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / American / African American & Black Studies

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.B585 M37 2023 (print) | LCC PN1995.9.B585 (ebook) | DDC 791.43089/96073dc23/20220811

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022030917

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022030918

They rode with white Texans, Mexicans, and Indians. All the real cowboysblack, brown, red and whiteshared the same jobs and dangers. They ate the same food and slept on the same ground; but when the long drives ended and the great plains were tamed and fenced, the trails ended too. The cattle were fenced in, the Negroes fenced out. Years later, when history became myth and legend, when the cowboys became folk heroes, the Negroes were again fenced out. They had ridden through the real West, but they found no place in the West of fiction. That was peopled by tall, lean, tannedthough lily-white under the shirtheroes who rode through the purple sage made dangerous by dirty villains, red Indians and swarthy greasers, only occasionally being helped by good Indians and proud Spanish-Americans. Even the Chinese survived in fiction, if only as pigtailed caricatures who spoke a no tickee, no washee pidgin as they shuffled about the ranch houses. Although the stereotypes were sometimes grotesque, all but one of the races and nationalities of the real West appeared in fiction.

All but the Negro cowboy, who had vanished.

Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones, The Negro Cowboys

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

I have loved horses since I was eight years old. Well, thats not entirely true. There were days when I was afraid of them given their size and unfamiliarity. But for the most part, I really adored them. I started horseback riding the summer my parents sent me to Camp Auxilium in Newton, New Jersey. The camp was a Roman Catholic sleep-away summer retreat for girls, managed and run by a cadre of strict, caring nuns and a few itinerant priests who would visit to officiate mass. The nuns who ran the camp back then took us for pony rides one Wednesday afternoon. And just like that, I was hooked.

When the summer ended and I returned home, I begged my parents to take me to riding lessons. I also obsessed endlessly over horses. The time Id spent on horseback (or pony-back) had proven more transcendent than daily rosary recitations (particularly for a non-Catholic like me). I was fascinated by the way horses looked, how their coats felt, and the rhythms with which they moved at different gaits. Horses have a way of making you feel vibrantly alive and yet remarkably calm at any age. They give you a feeling of mastery and movement but with the mutually understood, yet unspoken, caveat that without them youre just a two-legged human.

I desperately wanted to continue riding. But growing up in Brooklyn meant there were few, if any, places to see horses, much less go riding. Miraculously, my mother and father scouted far and wide. Whether it was by searching in the yellow pages or hearing by word of mouth, they finally found a stable where I could take riding lessons. They had located Clove Lake Stables in Brighton on Staten Island, and I took my first lessons not far from the North Shore of Staten Island in the New Brighton neighborhood.

Clove Lake had changed hands over the years. Back in the late nineteenth century, from 1897 through the 1920s, the stables housed ice truck horses for the Richmond Ice Company, which had its headquarters on Clove Road. The company was incorporated in 1881 and was a shipper to points in the Carolinas, the Virginias, Georgia, and Tennessee. E. D. Haley, a resident of Maine, was the companys president and an ice dealer in New England and New York.

By the early to mid-twentieth century, the property had become home to Clove Lake Stables, a riding academy that in the 1950s was owned by the Franzreb family. Founders John and Adele Franzreb passed the business to their grandsons Jeffrey and Jarad Franzreb. When I started taking lessons, the outfit was a modest hunter-jumper barn still run by Franzreb family members. Sisters Merri and Grace offered English riding lessons, Western pleasure riding, hayrides, and horse shows, and occasionally fox hunted on weekends. Merri and Grace even took me to watch the National Horse Show at Madison Square Garden, which, for me, was more magical than a three-ring circus.

As impressionable as I was, and as formative as those days were, my father and I found the trek to Staten Island long and arduous. It was especially tiring for my dad because my lessons were available on his one weekday off from work, since he usually worked Saturdays and some Sundays. Staten Island was far from our Brooklyn residence. So we eventually looked for alternatives closer to home. But I never forgot Merri, Grace, Clove Lake Stables, or the horses we rode there. Merri had been a tough and exacting instructor who instilled discipline, confidence, and horsemanship. She was one of the many instructors who helped me develop a lifelong love of, and respect for, these truly majestic yet surprisingly forgiving animals.

As my parents and I searched for new places to ride, more and more venues were closing. Author Diana Shaman had documented the trend years several earlier in her October 2, 1977, New York Times article. Shaman wrote about the bleak fate of urban stables. Most of the hundreds of stables that once existed in metropolitan areas had either been torn down or were being converted to other usesand understandably so. Cities are not a natural or particularly hospitable habitat for horses. Nowhere is this more evident than in the recent film Concrete Cowboy (Ricky Staub, 2020), which addressed the struggles of the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Director Ricky Staub aptly demonstrated how challenging it can be to maintain horses in urban centers and that such locations are usually not amenable to quality horse care regardless of how passionately caretakers are devoted to horsemanship and animal husbandry. While there are exceptions to the rule (such as the Compton Cowboys in Los Angeles and the Compton Jr. Posse), cities are typically ill-disposed to horses and horse care. Urban centers generally lack the open, green-space environments where horses naturally roam, dwell, and normally thrive.