The Complete Works of HERODAS (fl. 3rd century BC)  Contents

Contents  Delphi Classics 2021 Version 1

Delphi Classics 2021 Version 1  Browse Ancient Classics

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of HERODAS

The Complete Works of HERODAS  By Delphi Classics, 2021

By Delphi Classics, 2021

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Herodas First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by Delphi Classics. Delphi Classics, 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. S. S.

Buck Translation, 1921

CONTENTS

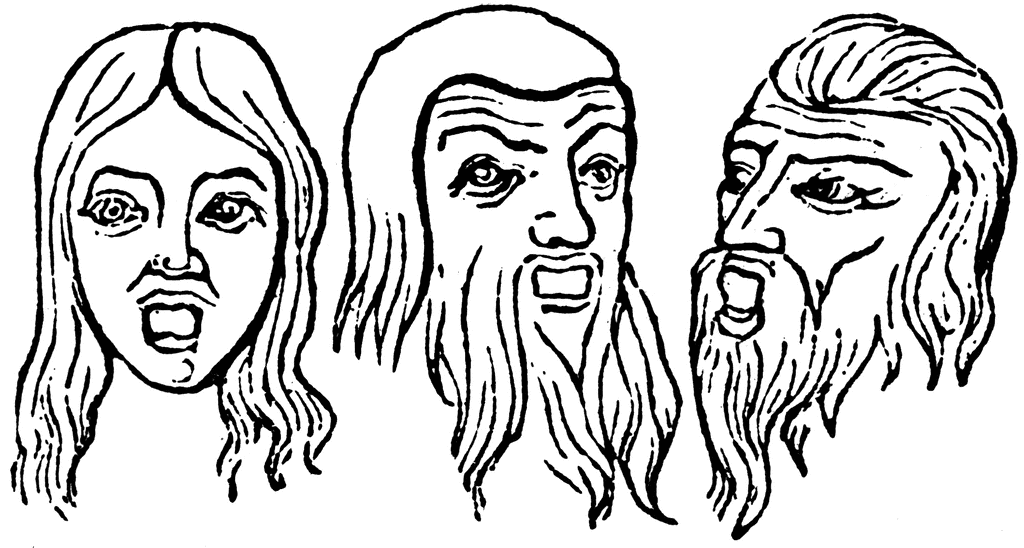

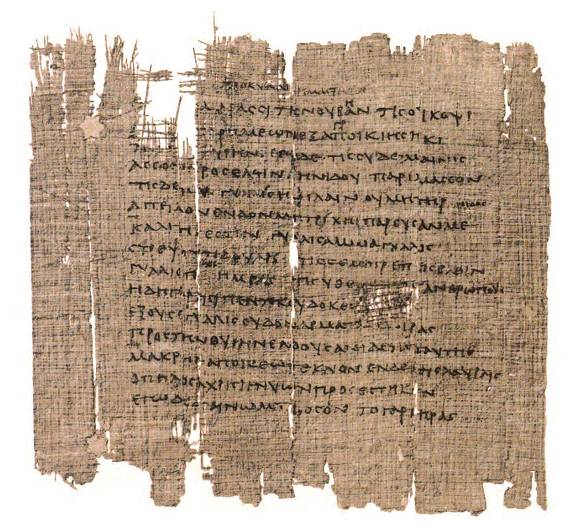

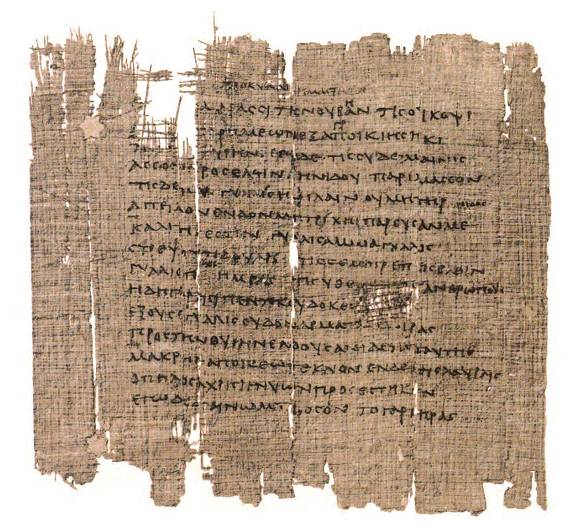

The first column of the Herodas papyrus, showing Mime 1. 115.

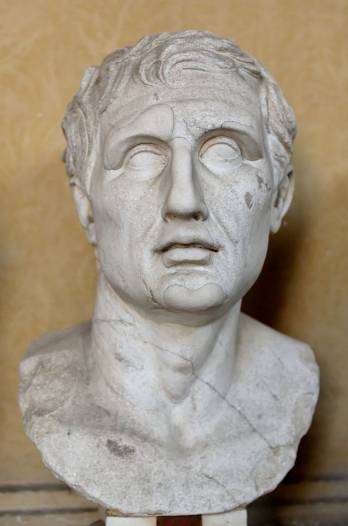

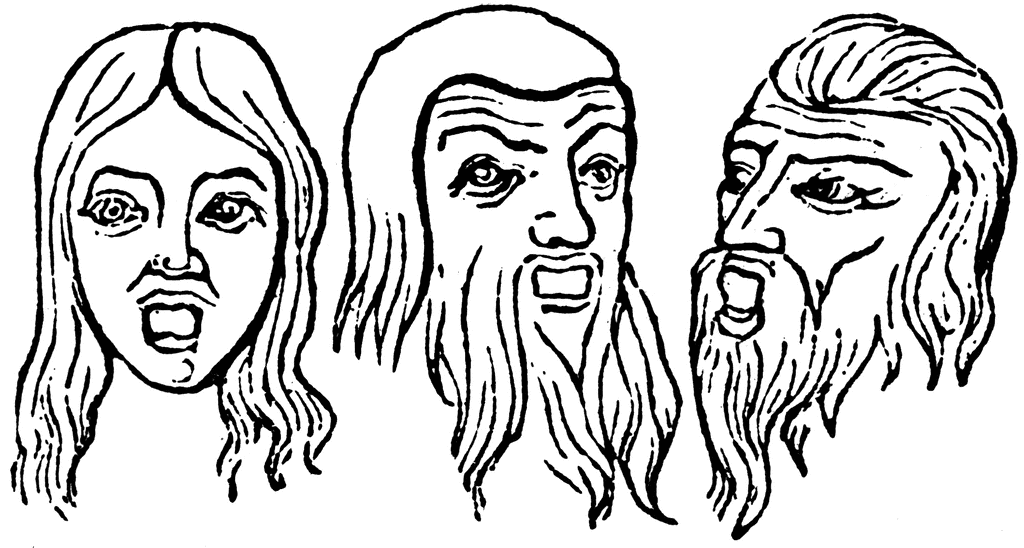

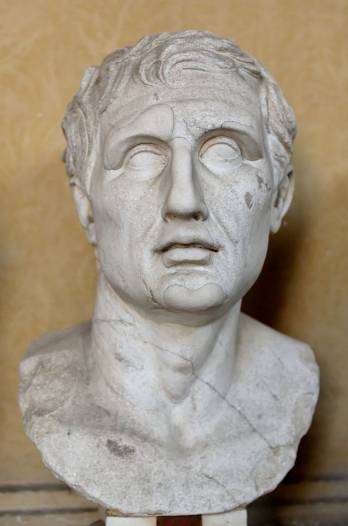

Bust of the Greek playwright Menander; Roman copy of the Imperial era, after a Greek original (c. 343291 BC) Menanders plays, now mostly lost, were likely a great source of influence for Herodas Mimes.

INTRODUCTION

The Mimes of Herondas or Herodas have been known to us only since the discovery and publication of the Kenyon MS. by the British Museum in 1891.

Previous to that time, this Author was known only by a few quotations in Athenus and a comment in a letter from Pliny the Younger to Autonius. As nearly as can be determined, the Mimes were written about the middle of the third century B. C. and, very possibly, at Kos, a small Greek island near the coast of Asia Minor about midway between the Samos and Rhodes. The island was noted for its precinct of Asklepios the scene of the fourth Mime which contained several temples and buildings, with groves and porticoes; and was also the seat of a considerable culture. While the Author used a poetic form, employing the scazon or lame iambic, he was essentially a Realist.

His scenes deal with popular life and are written in a naturalistic language, without flights of imagination, straining with poetic images or studied description or comment. For an extra touch, they give us a popular proverb rather than a mythological reference. It is thus, as a bald and undistorted picture of the intimate life of the period, that the Mimes are of the utmost importance, not only to students but also to more general readers who have, however, a certain leaning toward antiquity and appreciate the opportunity of seeing, intimately, these interesting phases of Greek life. The women with their gossip and scandal, the voluble cobble, the shiftless slaves, the brothel-keeper whose pompous court speech is almost a burlesque, drawn vividly with a few brief touches, are almost as human to us, to-day, as they must have been, to other readers, over two thousand years ago. The Kenyon MS. of Herondas from the Fayum the only one known is much damaged from worms and breaks, especially toward the end and, in other places, has been rubbed until it is almost impossible to decipher.

A rather uncertain dialect and frequent proverbial passages, not always clear, present additional difficulties. Therefore, an accurate, word for word translation is impossible. It has not even been definitely settled just which characters speak, in some parts of the Mimes, as the original does not always indicate the different speakers and the divisions that are given are simply by marks and not by names. The seventh Mime is seriously broken up; the eighth is hardly more than a fragment. And a few additional fragments, including some for the eighth Mime, discovered in 1900, are not of much value for restorations of general literary interest. As given here, the eight Mimes include all that we have, at this time, of Herondas, coherent enough for mention, except a fragment with the Authors rather epigrammatic remark addressed to Gryllos: When you have passed the bounds of three-score years, O Gryllos, Gryllos, die and turn to dust.

For life beyond that point is dark and the glory of life is obscured. It has been the aim of the present Translator to present a popular, readable version only, ignoring disputed points of interest only to critical students and using his own conjectural readings where necessary but including all passages where any sort of an intelligent reading is at all possible. Some of the subjects handled are certainly informal; but the situations are portrayed convincingly and in language to which, certainly, no objection can be taken. Acknowledgment is made to the literal French prose rendering of Pierre Quillard, second edition, Paris 1900, which has, in the main, been followed in connection with the text and exhaustive commentary prepared by J. Arbuthnot Nairn, M.A., and published in 1904. The tentative, partial translation of the first six Mimes by the late John Addington Symonds in his Studies of the Greek Poets, third edition, 1893, has also been consulted.

But this rendering, which bristles with the most startling interpretations, in addition to being abridged, cannot, today, be taken very seriously. The large part given to women in the Mimes leads us into reflection over the standing of antique, as compared with present-day, women. And, if we may believe that the position of women in the world always has, and no doubt always will depend to a greater extent than is, perhaps, realized on the women themselves, our inevitable conclusion is flattering to those with whom Herondas was acquainted. Certainly, the women of the antique world, although occupying what is ordinarily considered a subjective position, kept more truly a real and passionate standard of womanhood. Whether simply courtesans like Myrtale, moderately corrupt dilettantes like Koritto or no more than average housewives like Phile, they touched more easily the greatest heights of happiness or sounded the deepest abysses of woe in either case, however, realizing their sex to the fullest. And the most erudite and persistent modern advocate of womans rights can never prove convincingly that this realization through submission, not assertion possible now with the with the additional glory of complete consciousness and its conventional fruition, has not always been, and will not always be, the real intention of Nature; nor that, in wilfully departing from it, the present-day woman does not seek to barter her heritage for a mess of pottage of very uncertain quality.

Next page

Contents

Contents  Delphi Classics 2021 Version 1

Delphi Classics 2021 Version 1  Browse Ancient Classics

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of HERODAS

The Complete Works of HERODAS  By Delphi Classics, 2021

By Delphi Classics, 2021

The first column of the Herodas papyrus, showing Mime 1. 115.

The first column of the Herodas papyrus, showing Mime 1. 115.  Bust of the Greek playwright Menander; Roman copy of the Imperial era, after a Greek original (c. 343291 BC) Menanders plays, now mostly lost, were likely a great source of influence for Herodas Mimes.

Bust of the Greek playwright Menander; Roman copy of the Imperial era, after a Greek original (c. 343291 BC) Menanders plays, now mostly lost, were likely a great source of influence for Herodas Mimes.