For my students.

Simone Giertz is hunting robots. No, not rabbitsrobots. In a special episode of her popular YouTube series, the self-proclaimed Queen of Shitty Robots explores what she calls Americas obsession with hunting. Plot twist: she is a vegetarian. I just dont want to have to kill any animals, she reveals to her 1,880,211 subscribers. But robots? I would be fine with killing some robots (2018). This sentiment falls in line with the guiding theme of Giertzs show, which deflates popular conceptions of automation as efficient and clean, producing instead awkward and messy automata that poke fun at technological progress. The Hunting episode sends Giertz on a training regimen that involves fishing for underwater drones (and of course ripping her ridiculous rubber pants in the process), followed by an archery lesson in which she skewers cardboard cutouts of pickles, airline food, and period blood. Inspired by the experience of launching arrows, Giertz creates the object of her hunting expedition: an uncanny robotic deer whose resin head and legs, actuated by windshield wiper motors, jerk back and forth mechanically. The ridiculous legs are ultimately useless appendages, given that the deer is set on the chassis of a mobility chair equipped with remote control. By the end of the episode, Simone hits the kill zone (a bladder filled with hot sauce tucked into the deers side), eats a portion of her prey (a brick of braised tofu screwed to the exterior shell of the deer), and walks off into the sunset with her new cybernetic kin.

It would be easy to spend an entire chapter unpacking this ludicrous and irreverent video. But deep reading of popular culture is not the guiding method of this book. I include the Shitty Robot episode because it provides an evocative entry point. If Giertz was a media studies scholar, a philosopher of technology, or, more precisely, a critical maker, she might accompany her hunting video with an essay about nonhuman kin, the politics of technological prostheses, and the clash between an antiseptic future of efficient robots and the bleeding, sweating, and shitting animals that will create them. But Giertz is not making media theory. Still, what her often-vulgar design performances do best is underscore the strange scene of an abject species capable of, and even obsessed with, replacing itself with efficient machines. While this is not exactly the topic of Making Media Theory , it is certainly a guiding premise. This book asks readers to reflect critically on the performance of fleshly bodies that make media technologiesa performance that can lead to the production of some rather precarious human-machine entanglements or, in Simones terms, shitty robots.

More precisely, this book is an effort to document and share a certain way of studying media that I have developed in my own research and teaching over the past fifteen or so years. Rather than just interpreting media and their effects, perhaps viewing them as objects-to-think-with, I have endeavored to make my own technological objects-to-think-with. The result is a conspicuously embodied way of thinking critically with and about media, and it has produced strange things, such as a penny-farthing bicycle with sensors that control a large video projection and a cedar and canvas canoe with touch-screen monitors wrapped in fishing line. I tried to define this practice in a 2012 article called Broken Tools and Misfit Toys: Adventures in Applied Media Theory. A few years later, in my book Necromedia, I demonstrated quite explicitly how Applied Media Theory works. Each chapter on death and technology in Necromedia is followed by a chapter describing a digital project (including the aforementioned penny-farthing and canoe) that I created to think through the media-theoretical claims in the book. Recently, I have stopped using the term Applied Media Theory because the focus on application too narrowly circumscribes the practices I have been trying to develop and foster in my students. These practices do not simply attempt to embody theory in a fully formed made thing; instead, they rely on a generative feedback loop that requires shuttling back and forth between theorizing and making.

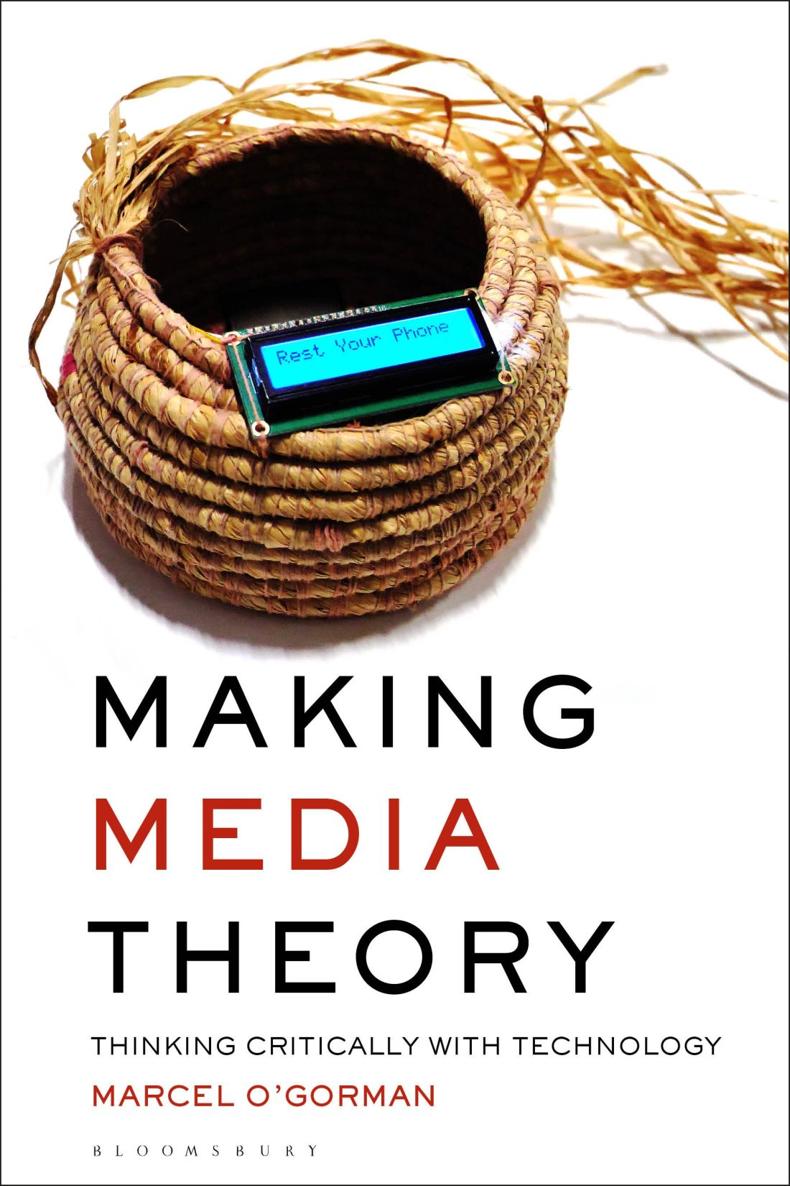

Whereas Necromedia documents my own projects, Making Media Theory focuses primarily on my students projects and encourages readers to make their own objects-to-think-with. For this reason, I have sandwiched five DIY workshops into this book, complete with instructions and evocative discussion questions. Readers are prompted, for example, to philosophize with conductive play dough and to critically hack a kit-of-parts designed for making a useless box. These exercises reflect directly on the chapter topics, which unpack such issues as the value of uselessness, the importance of digital rituals, and the politics of cultural appropriationall in a media-centric context. I do not expect that readers will actually make all of these projects, some of which include materials that may be inaccessible to readers or code that may no longer function by the time this book goes to press. The workshops can indeed be attempted (they are based on projects I have taught myself several times), but I include them primarily as prompts for readers to make media theory by combining their own research questions with fabrication materials at their disposal.

I should make it clear that this is not a design book per se. Still, the methods it recommends could easily be categorized as what Bruce and Stephanie Tharp have called discursive design in their gorgeously illustrated tome of the same title. Making Media Theory is obviously not a tome. Nor is it gorgeous, and there is no expectation that the projects this book recommends should be aesthetically pleasing. The practices outlined in the book run parallel to those in the loosely categorized field of critical design, as exemplified in the work of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Anne Balsamo, Natalie Jeremijenko, Mary Flanagan, and others. Matt Malpass has attempted to firmly establish this field in his book Critical Design in Context: History, Theory, and Practice . Above all, I want to champion the work of Daniela K. Rosner, whose book Critical Fabulations: Reworking the Methods and Margins of Design was published only after I had completed a full draft of this manuscript. Rosner calls for practices of designing and making that catalyze new embodied ways of knowing... [and] draw attention to the contested nature of knowledge production while caring for their repercussion (17).

As the allusion to broken tools and misfit toys suggests, this book was not written for classically trained artists or what Rosner calls cosmopolitan designers committed to ideals of mastery and perfection (2018: 127). This is not to say that these individuals would have nothing to gain from reading this book. Making Media Theory was written for anyone interested in how to integrate the body more conspicuously into acts of understanding media. In Chapter 1, I recommend a practice called crapentry , which takes the will to mastery out of the exercise of making, injecting humor, play, and the acceptance of failure into the process. I urge readers to take risks, to become producers of technoculture rather than consumers of it. If media technologies have reduced physical r isk by allowing us to conquer distances without leaving home and to communicate anonymously with large audiences through a screen, making media theory puts physical risk back into the equation. [M]aking, Patrick Jagoda suggests, brings with it materiality and all its creative possibilities and reminders of finitude (362). As I discuss in Chapter 6 in my description of Robin Wall Kimmerer trying to weave a basket from stubborn strips of black ash, this book asks readers to embrace the tension between human bodies and the environments they inhabit. Media are our infrastructures of being, John Durham Peters proclaims in The Marvelous Clouds . Living technologically involves a ceaseless interplay of adoption and adaptation, a contest of bodies being violently pushed and willingly pulled into complex networks of things that offer resistance. Making media theory can provide a controlled environment to rehearse and think through these tensions; it offers opportunities, in the words of Tim Ingold, to enter the grain of the worlds becoming (2013: 25). The word thinkering is instructive here, suggesting that handiwork can prompt reflection and, in this case, close attention to the media with which our being is interwoven. I would like to think that making media theory, by implicating bodies in conspicuous ways, combines careful reflection with what Donna Haraway has called critical diffraction: diffraction patterns record the passage of difference, interaction, and interference (1997: 430).