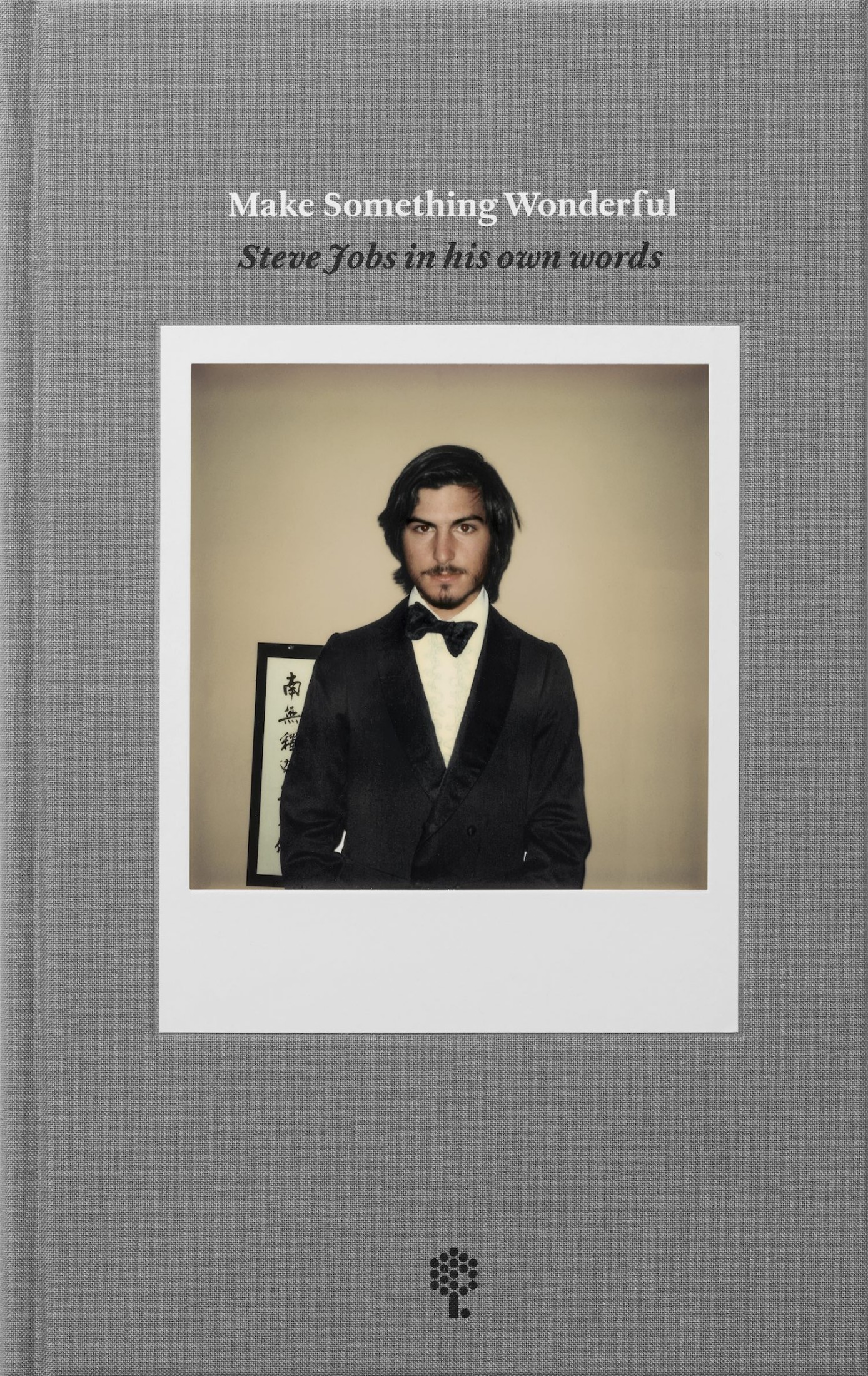

The best way to understand a person is to listen to that person directly. And the best way to understand Steve is to listen to what he said and wrote over the course of his life. His wordsin speeches, interviews, and emailsoffer a window into how he thought. And he was an exquisite thinker.

Much of whats in these pages reflects guiding themes of Steves life: his sense of the worlds that would emerge from marrying the arts and technology; his unbelievable rigor, which he imposed first and most strenuously on himself; his tenacity in pursuit of assembling and leading great teams; and perhaps, above all, his insights into what it means to be human.

Steve once told a group of students, You appear, have a chance to blaze in the sky, then you disappear. He gave an extraordinary amount of thought to how best to use our fleeting time. He was compelled by the notion of being part of the arc of human existence, animated by the thought that heor that any of usmight elevate or expedite human progress.

It is hard enough to see what is already there, to gain a clear view. Steves gift was greater still: he saw clearly what was not there, what could be there, what had to be there. His mind was never a captive of reality. Quite the contrary: he imagined what reality lacked and set out to remedy it. His ideas were not arguments, but intuitions, born of a true inner freedom and an epic sense of possibility.

In these pages, Steve drafts and refines. He stumbles, grows, and changes. But always, always, he retains that sense of possibility. I hope these selections ignite in you the understanding that drove him: that everything that makes up what we call life was made by people no smarter, no more capable, than we are; that our world is not fixedand so we can change it for the better.

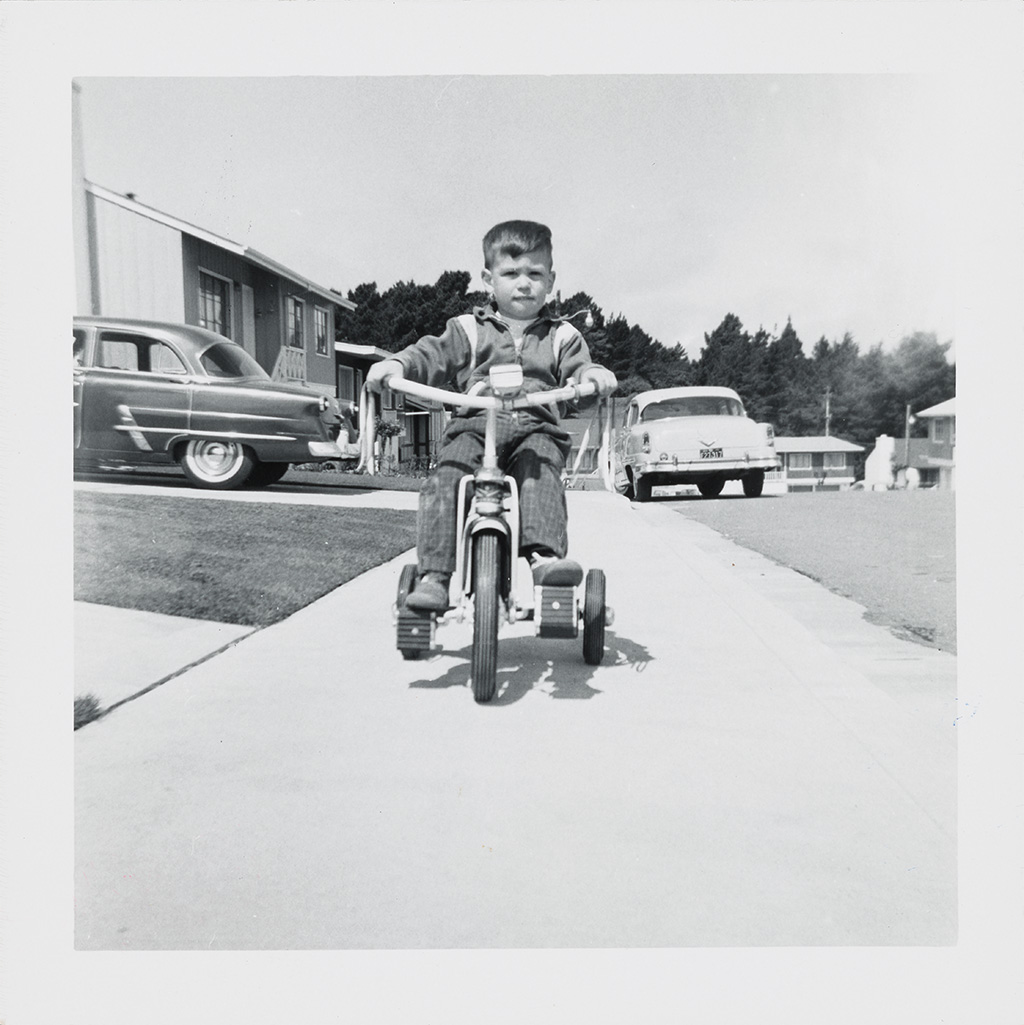

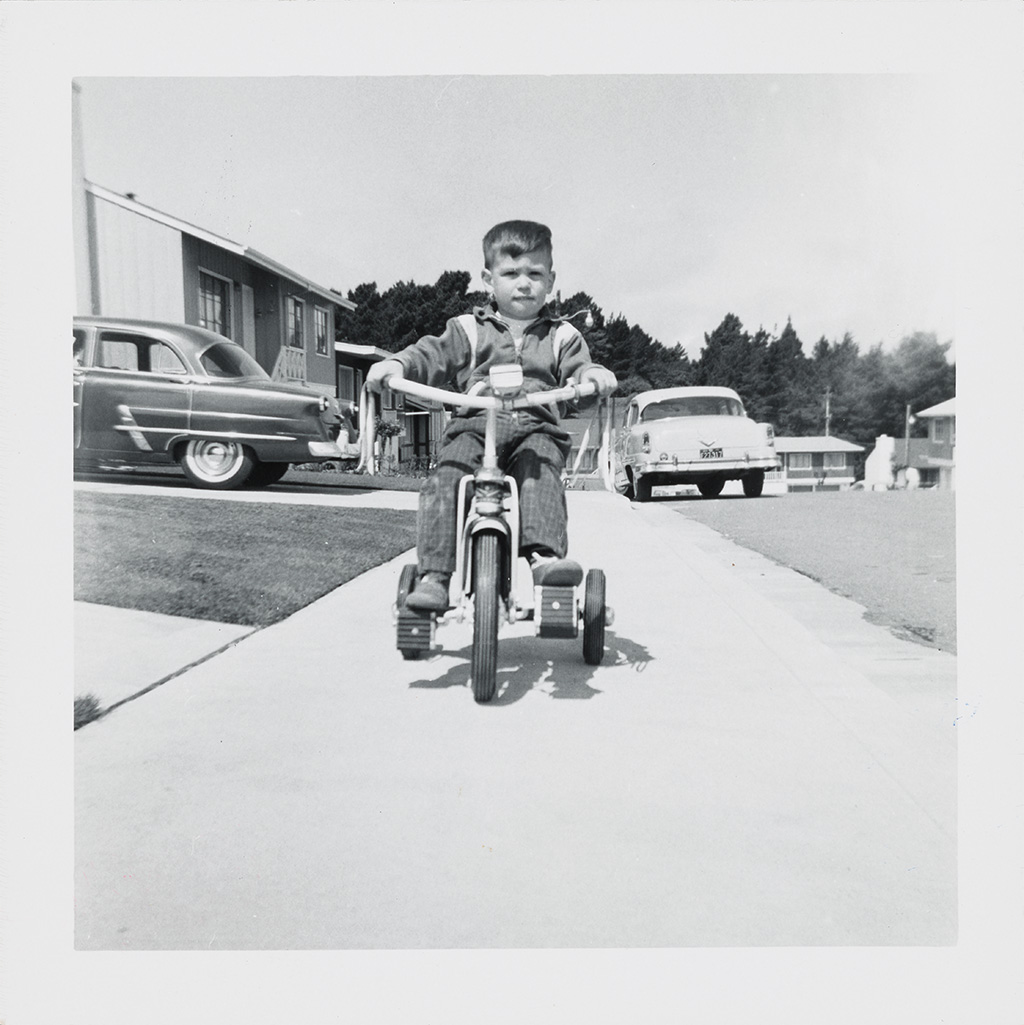

Steve at two. He later called computers a bicycle of the mind.

Preface: Steve on His Childhood and Young Adulthood

Steve typically kept his personal life private, but he did occasionally talk about growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was a time when engineers and programmers began flooding into what came to be known as Silicon Valley.

In 1995, he recorded an oral history for the Smithsonian.

I was very lucky. I had a father, named Paul, who was a pretty remarkable man. He never graduated from high school. He joined the Coast Guard in World War II and ferried troops around the world for General Patton, and I think he was always getting into trouble and getting busted down to Private. He was a machinist by trade and worked very hard and was kind of a genius with his hands.

He had a workbench out in the garage where, when I was about five or six, he sectioned off a little piece of it and said, Steve, this is your workbench now. And he gave me some of his smaller tools and showed me how to use a hammer and saw and how to build things. It really was very good for me. He spent a lot of time with me, teaching me how to build things, take things apart, put things back together.

One of the things that he touched upon was electronics. He did not have a deep understanding of electronics himself, but hed encountered electronics a lot in automobiles and other things that he would fix. He showed me the rudiments of electronics, and I got very interested in that.

I grew up in Silicon Valley. My parents moved from San Francisco to Mountain View when I was five. My dad got transferred, and that was right in the heart of Silicon Valley, so there were engineers all around. Silicon Valley, for the most part, at that time, was still orchardsapricot orchards and prune orchardsand it was really paradise. I remember almost every day the air being crystal clear, where you could see from one end of the valley to the other. It was really the most wonderful place in the world to grow up.

There was a man that moved in down the street, maybe about six or seven houses down the block, who was new in the neighborhood with his wife. And it turned out that he was an engineer at Hewlett-Packard and he was a ham-radio operator and really into electronics. What he did to get to know the kids on the block was rather a strange thing: he put out a carbon microphone and a battery and a speaker on his driveway, where you could talk into the microphone and your voice would be amplified by the speaker. Kind of a strange thing when you move into a neighborhood, but thats what he did.

I got to know this man, whose name was Larry Lang, and he taught me a lot of electronics. He was great. He used to build Heathkits. Heathkits were really great. Heathkits were these products that you would buy in kit form. You actually paid more money for them than if you just went and bought the finished product, if it was available. These Heathkits would come with these detailed manuals about how to put this thing together, and all the parts would be laid out in a certain way and color coded. Youd actually build this thing yourself.

I would say that gave one several things. It gave one an understanding of what was inside a finished product and how it worked, because it would include a theory of operation. But maybe even more importantly, it gave one the sense that one could build the things that one saw around oneself in the universe. These things were not mysteries anymore. I mean, you looked at a television set, and you would think, I havent built one of thosebut I could. Theres one of those in the Heathkit catalog, and Ive built two other Heathkits, so I could build a television set. Things became much more clear that they were the results of human creation, not these magical things that just appeared in ones environment that one had no knowledge of their interiors. It gave a tremendous degree of self-confidence that, through exploration and learning, one could understand seemingly very complex things in ones environment. My childhood was very fortunate in that way.

School was pretty hard for me at the beginning. My mother taught me how to read before I got to school, and so when I got there I really just wanted to do two things: I wanted to read books, because I loved reading books, and I wanted to go outside and chase butterflies. You know, do the things that five-year-olds like to do. I encountered authority of a different kind than I had ever encountered before, and I did not like it. And they really almost got me. They came this close to really beating any curiosity out of me.

By the time I was in third grade, I had a good buddy of mine, Rick Ferrentino, and the only way we had fun was to create mischief. I remember there was a big bike rack where everybody put their bikes, maybe a hundred bikes in this rackand we traded everybody our lock combinations for theirs on an individual basis. Then [we] went out one day and put everybodys lock on everybody elses bike, and it took them until about ten oclock that night to get all the bikes sorted out. We set off explosives in teachers desks. We got kicked out of school a lot.

In fourth grade I encountered one of the other saints of my life. They were going to put me and Rick Ferrentino into the same fourth-grade class, and the principal said at the last minute, No, bad idea. Separate them. So this teacher, Mrs. Hill, said, Ill take one of them. She taught the advanced fourth-grade class, and thank God I was the random one that got put in the class. She watched me for about two weeks and then approached me. She said, Steven, Ill tell you what. Ill make you a deal. I have this math workbook, and if you take it home and finish it on your own without any help, and you bring it back to me, if you get it 80 percent right, I will give you five dollars and one of these really big suckers. She [had] bought [a sucker], and she held it out in front of meone of these giant things.