Table of Contents

Also by Michael Moritz (with A. Barrett Seaman)

Going for Broke: The Chrysler Story

For the best additions since

the first edition:

HCH JWM WJM

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dozens of people agreed to be interviewed for this book. Many did not. I hope that those who opened their doors and interrupted more profitable pursuits dont feel they wasted their time. Others kindly let me rummage through filing cabinets and peer at photograph albums while the editors of the San Jose Mercury News made me welcome in their morgue. Dick Duncan, Times chief of correspondents, tolerated another of my disruptive excursions and gave me a leave of absence. Ben Cate, Times West Coast Bureau chief, provided the unwavering support that those who have worked for him will understand. Catazza Jones improved a first draft, Julian Bach took care of business, and Maria Guarnaschelli applied a deft and graceful touch.

MICHAEL MORITZ

Potrero Hill

Spring 1984

PROLOGUE

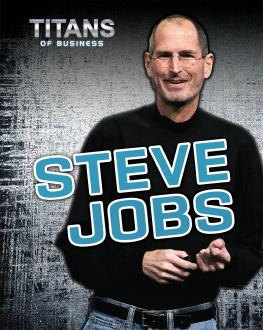

When Time engages in its annual ritual of announcing the selection for its person of the year, I am inevitably reminded of an occasion, almost thirty years ago, when a similar bulletin caught me in its crosshairs. At the dawn of 1982, while I was on leave from my position as a correspondent in Times San Francisco bureau, the magazines editors decided to nominate the computer as its person of the year. Buried inside this issue was a profile, to which I had contributed, of Apples co-founder Steve Jobs. It was there that my troubles began.

It was hard to say who was more incensed by Times storyJobs or me. Steve rightly took umbrage over his portrayal and what he saw as a grotesque betrayal of confidences, while I was equally distraught by the way in which material I had arduously gathered for a book about Apple was siphoned, filtered, and poisoned with a gossipy benzene by an editor in New York whose regular task was to chronicle the wayward world of rock-and-roll music. Steve made no secret of his anger and left a torrent of messages on the answering machine I kept in my converted earthquake cottage at the foot of San Franciscos Potrero Hill. He, understandably, banished me from Apple and forbade anyone in his orbit to talk to me.

The experience made me decide that I would never again work anywhere I could not exert a large amount of control over my own destiny or where I would be paid by the word. I finished my leave; published my book, The Little Kingdom: The Private Story of Apple Computer, which I felt, unlike the unfortunate magazine article, presented a balanced portrait of the young Steve Jobs; honored my obligation to Time and, at the first opportunity, fled to become, at the outset, half of the entire workforce of a specialty publishing business that many years laterlong after I had entered the venture capital fieldwas acquired by Dow Jones.

In the three decades since, I have sometimes wondered about the quirks of fate that have connected me with Steve. Had I not been in my twenties, Time would probably never have posted me to San Francisco, where I happened to be of the same generation that was starting computer, software and biotech companies. Had I not met Steve, I would not have encountered Don Valentine, the founder of Sequoia Capital, and an original investor in Apple. Had I not met Don, I would never have found myself interviewing to become the lowest man on Sequoia Capitals short totem pole. Had I not written about Apple, where I became obsessed with the then-unchronicled tale of its very early days, I would never have thought hard about the traits and accidents that shape a company. Had I not started learning the ropes of the venture trade in the mid 1980s, I would never have had the good luck that has flowed my way. And, had I not met Steve and Don, I would never have understood why its best not to think like everyone else.

Im sure that when Steve was a teenager, growing up in Los Altos, California, he could never have imagined that some day he would be at the helm of a company whose headquarters, according to Google maps, is three street turns and 1.6 miles from the front gate of his high school, that has sold over 200 million iPods, a billion iTunes songs, 26 million iPhones, and over 60 million computers since 1996; or that his face would have adorned the front cover of Fortune on twelve occasions; or that, almost as a sideline, he would single-handedly finance and help shape Pixar, the computer animation company that has rung up more than $5 billion in cumulative box office sales from ten immensely popular movies. He might wonder too about those twists and turns that helped make him what he is: the fact that his boyhood was spent in an area that, back then, had not even been labeled Silicon Valley; that Apples co-founder, Stephen Wozniak, was a boyhood chum; that he worked one summer as a lab technician at Atari, the maker of Pong, the first popular arcade video game; that Ataris founder, Nolan Bushnell, had raised money from Don Valentine; and that Nolan was one of the people who steered Steve towards Don. Such are the haphazard breadcrumbs strewn along the trail of life.

These days, thanks to the rough and tumble experiences of almost twenty-five years in the venture capital business, I have developed what I hope is a more refined perspective on the extraordinary accomplishments of Steves business lifeone that deserves to be ranked amongst the greatest of any American, living or dead.

Steve is the CEO of Apple but, much more importantly (even though his business card does not say this), he is a founder of the company. As the history of Apple shows, there is no greater distance known to man than the single footfall that separates a CEO from a founder. CEOs are, for the most part, products of educational and institutional breeding. Founders or, at least, the very best of them, are unstoppable, irrepressable forces of nature. Of the many founders Ive encountered, Steve is the most captivating. Steve, more than any one other person, has turned modern electronics into objects of desire.

Steve has always possessed the soul of the questioning poetsomeone a little removed from the rest of us who, from an early age, beat his own path. Had he been born at a different time, its easy to see how he would have hopped freight cars and followed his star. (It is not a coincidence that he and Apple helped underwrite Martin Scorceses No Direction Home, the absorbing biopic of Bob Dylan.) Steve was adopted and raised by well-meaning parents who never had much money. He was attracted by Reed College, a school that exerts an unusual appeal for bright and thoughtful teenagers, and which, in the 1970s, was tailor-made for any child who wished he had been at Woodstock. It was there that a calligraphy class sharpened his sense of the aestheticthat influence is still apparent in all Apple products and advertising.

Jobss critics will say he can be willful, obdurate, irascible, temperamental, and stubbornbut show me someone who has achieved anything meaningful who, from time to time, doesnt display these characteristics, who is not a perfectionist. There is also the mischievous, calculating, suspicious twinkle of the souk about Steve. He is an insistent, persuasive and mesmerizing salesmanabout the only man I know with the audacity to adorn bus shelters nationwide with advertisements for a product as mundane as a wireless mouse. But he is also a man who, decades ago, was kind enough make visits to a hospital to visit a CEO felled by a stroke and who, recently, in an avuncular fashion, has offered younger Silicon Valley CEOs generous advice.