Ecstasy and the Rise of

the Chemical Generation

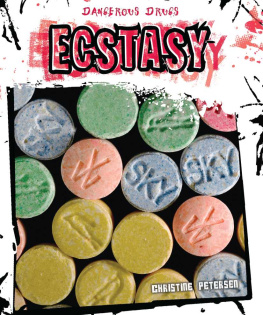

Drug users are no longer a mad, bad or immoral minority. Using drugs is normal for the chemical generation, and the drug that defines them is ecstasy. This book about ecstasy users' lives is based on one of the biggest government-funded projects ever undertaken and gives voice to the chemical generation for the first time.

The effects of the manufacture, distribution and use of ecstasy are now being felt across much of the globe. In the UK, where the study was conducted, over fifty per cent of young people use drugs, a quarter of them regularly. The people in this book are ordinary, decent, family-loving people, with normal lives, normal problems and normal aspirations. Through their own words we hear how they first started using ecstasy, how they use it in different ways, why clubbing and raving are so important, how good sex is on ecstasy, how they chill out, how they come down, what problems they have encountered and why they quit.

And what happened to these normal people when they used ecstasy? Nothing. Yet.

This path-breaking book ends by trying to answer the question on the lips of every member of the chemical generation: what are the long-term effects of ecstasy? Because we can't answer them, the authors claim, we are failing in our duty to our children: telling them not to take ecstasy is as alienating as it is pointless.

Richard Hammersley is Professor at the Health and Social Sciences Institute at the University of Essex; Furzana Khan is Research and Information Officer for the Glasgow Council for the Voluntary Sector; Jason Ditton is Professor of Criminology at the University of Sheffield and Director of the Scottish Centre for Criminology in Glasgow.

Ecstasy and the

Rise of the Chemical

Generation

Richard Hammersley

University of Essex, UK

Furzana Khan

Glasglow Council for the Voluntary

Sector, UK

and

Jason Ditton

University of Sheffield, UK

London and New York

First published 2002

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

2002 Richard Hammersley, Furzana Khan and Jason Ditton

Typeset by Expo Holdings, Malaysia

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 0-415-27040-5 (hbk)

ISBN: 0-415-27041-3 (pbk)

Contents

List of Tables

Preface

As the final touches are being put to this book in the earliest days of the 21st century, the 1990s seem, in retrospect, to be a curious decade. We had fully expected it to be a decade of the stimulants in the late 1980s, and so it turned out to be. Ecstasy, the stimulant which is the focus of this book, had a more curious decade than most drugs. The early 1990s saw a celebratory endorsement of it, as bars across the middle of England closed, and promptly reopened as alcohol-free clubs. By the middle of the decade, alcohol had crept back onto the scene (it has been provocatively suggested that the so-called alco-pops were introduced by the drinks industry not to ensnare children with their sweet taste, but instead to wean Ecstasy users back to more conventional and more dangerous drugs), and unofficial self-organised raves were being broken up more frequently by the police. The tabloids rubbed their hands with glee as club deaths could be laid by them at Ecstasy's door. By the late 1990s, things fell into perspective. The Chemical Generation, or Generation X, had not migrated into the depressed generation that some had foretold. Hundreds of thousands of doses of Ecstasy are believed to be consumed each week, yet the death rate has not risen, and for many of the deaths associated with Ecstasy (at least in the media) it remains unproven that Ecstasy caused death.

This book reports two of the three separate studies of the use of Ecstasy undertaken by the authors during the 1990s. The major study (which is reported in the five main chapters) compromised quantitative interviews with 229 Ecstasy users, 22 of whom were interviewed qualitatively and in depth. These interviews took place between December 1993 and June 1995. In early 1999, we managed to trace seven of the 22, and re-interviewed them.

In 1994, we studied the information needs of 38 young Ecstasy users. All 38 took part in one of six discussion groups, and 21 of the participants were later interviewed in depth. This is reported in the Appendix.

This book is not aimed exclusively at an academic audience. Quantitative analysis is dealt with lightly in the main text, and more space than would otherwise be appropriate is given to the words of the 22 users we interviewed with a tape-recorder to hand. However, our main quantitative findings have been validated by the scientific peer-review system, and references to these published articles are given where necessary. As we were making final changes to the book, in January 2000, the clubbing magazine Mixmag published the results of a large survey of its readers' drug-using habits. The only major differences we noticed between those findings and the ones in this book were that Ecstasy use seems to have become even more common. For instance, more of the people who replied to the survey had taken ecstasy during the previous month than had taken cannabis. Also, cocaine seemed to becoming more common again.

Two final things. It is a convention amongst researchers working with qualitative data in Scotland to attempt to retain the Scottishness of the original speech, while making it readable elsewhere. This produces tensions between accurate transcribing on the one hand, and avoiding turning Scottish speech into exotic or inarticulate English, rather than as coherent Scottish, on the other. Our solution is to convert most words to standard English spellings, but to retain Scottish grammar and dialect words. We have also retained Glaswegian slang words and specialised drugs slang, some of which have never been dignified with dictionary definitions. We provide working definitions of these as appropriate. Finally, in the text, we refer to Ecstasy like that: with an initial capital even if the word appears in the middle of a sentence. In quoted speech, it is referred to as E or Eccy, several of them as Eees, consuming them as Eeeing and the result of doing so as being Eeed. Simply because that what it sounds like people are saying.

NOTES

See Davies, J. and Ditton, J., The 1990s: Decade of the stimulants? British Journal of Addiction, 1990, 85 (6): 811-813.

In 1995, we accompanied a group of 203 young people on a rave package tour to a well-known Mediterranean island, and this is reported in Elliott, L., Morrison, a., Ditton, J., Farrall, S., Short, E., Cowan, L. and Gruer, L., Alcohol, drug use and sexual behaviour of young adults on a Mediterranean holiday,