If you purchased this ebook directly from oreilly.com, you have the following benefits:

If you purchased this ebook from another retailer, you can upgrade your ebook to take advantage of all these benefits for just $4.99. to access your ebook upgrade.

Foreword: Any Questions?

Henry Jenkins

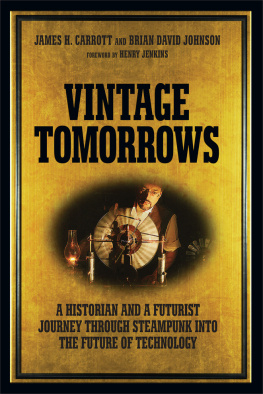

Vintage Tomorrows started as a conversation between a cultural historian and a futurist: what might steampunk (as a genre, movement, lifestyle, and philosophy) teach us about the ways people are thinking about their relationships with technology? They found it a gripping topic, they set out to talk with others, and the conversation kept broadening outward, as they found more thinking partners, many of whom were already talking through these questions together, and as one question led to another and another

Christopher Columbus sailed west to get east; these authors looked into our collective fantasies about the past (or rather yesterdays tomorrows) in order to better understand our shared desires for the future. Ultimately, the authors hope people will design and build better tools because we have a deeper understanding of what makes technologies meaningful for people who spend a lot of time re-imagining and retrofitting 19th century devices and gadgets. Makes sense to me.

I have been researching fan cultures for more than thirty years and participating in them for much longer, so let me put steampunk into a larger context. I am going to be painting with pretty broad strokes, so bear with me. Like the authors, I think something profound is going on here. Vintage Tomorrows compares it with the counter-cultures of the 1960s and I can follow them there. After all, as technology historian Fred Turner has suggested, the counterculture was the birthplace of todays cyberculture. For me, the explanation for all of this starts elsewherewith the origins of science fiction and of science fiction fandom, both of which have in turn influenced contemporary forms of participatory culture.

The first thing you need to understand is that science fiction fandom has always been a community of people who were drawn together because they wanted to ask questions and most of the people around them found this constant probing to be annoying. The communitys conversation started in the early part of the 20th century and hasnt slowed down since. Fandom doesnt simply exist to give fans a chance to talk with each other about the stories they enjoy. Science fiction stories exist to give fans something to talk about with each other. Speculation is the name of the game, and fans play that game better than anyone else.

The second thing you need to understand is that whatever steampunk is (and you will get lots of definitions here), it isnt Victorian science fiction. If you asked Victorians about science fiction, they would not have a clue what you were talking about, though science fiction as a genre was profoundly and permanently shaped by the Victorian imagination. While many Victorians desperately wanted to believe in the stability of the empire and the power of tradition to give order and meaning to their lives, they were actually living at a moment of profound and prolonged change. One reason we are so preoccupied with the Late Victorian period, today, is that it may have been the last time, prior to the digital revolution, when our society confronted such a dramatic shift in its basic technological infrastructure. New media is a state of mind; every old media was new once, and people had to confront the changed realities that those new technologies might on the ways they saw the world. One way we cope with the shock of the new is to look backwards, hoping that the shock of the old might counteract its impact. So, the digital revolution has invited us to reconsider The Victorian Internet, as Tom Standage described the Telegraph, and a range of other devices that look differently to us today thanks to our access to networked computers. Steampunk represents one of a number of new kinds of historical consciousness that are emerging as people try to put themselves in the places of previous generations as they underwent a media revolution.

Literary critic Jay Claytons delightful book, Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century in Postmodern Culture , explores many different connections people have drawn between the Victorian age and our own. Contrary to common stereotypes about rigid Victorian thinking, Clayton argues that the late 19th century was characterized by undisciplined culture: [The 19th century thinkers] thrived in an atmosphere that might be described as predisciplinary, a world in which the professional characteristics of science as a discipline had not yet been codifiedThese men and women had an irreverent attitude towards boundaries and an impatience with anything resembling intellectual restraint. They mixed science, engineering, and the arts as they pleased. Without too much exaggeration, they might be described as the nineteenth-century equivalent of hackers.

The Victorians witnessed dramatic changes in the technologies of transportation and production, but for my purposes, what seems most interesting is that there were changes in technologies for communication and reproduction, starting with photography and the telegraph, extending to cinema and the telephone, and finally, hitting critical mass with the phonograph and radio. Many of these new technologies emerged with the fantasy of speaking with the dead: the phonograph was sold, in part, as a way of recording and preserving a loved ones dying words; the radio took shape in part because people believed that tapping into the ether might be a good way to contact the spirits; and photography took shape, in part, around the desire of parents to cling to fading memories of their children in an age of devastating infant mortality. Photography, French film theorist Andre Bazin, told us, was born with a mummy complex. But, from the start, we used these new media to imagine the future in ever more tangible and concrete ways. So, go to the movies in the late 1900s and you would see magicians trying to imagine what it would be like to travel to the moon, or visit Coney Island and you might see Jules Vernes travel fantasies transformed into spectacular rides and attractions. This is how science fiction was born.

For science fiction to exist as a genre, the culture must experience such rapid change that people could recognize significant shifts over their own lifetime and thus begin to imagine a future that looks radically different from the present. A society where the same basic practices are handed down generation after generation has little use for science fiction. Another precondition may be the capacity of a people to recognize that things your society takes for granted are not the only natural or logical ways that people might live.